New York is shook. But how can an earthquake hit in the middle of a tectonic plate?

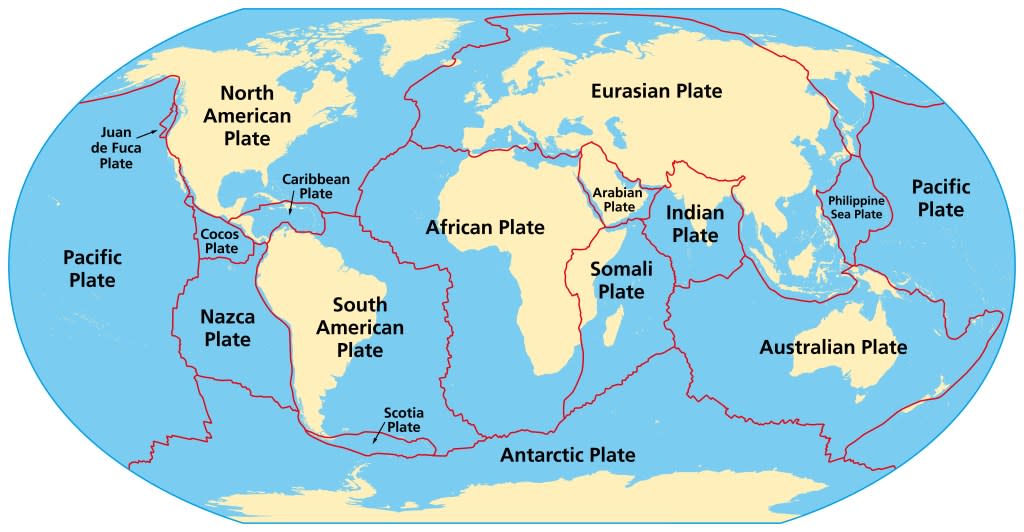

Take yourself back to fifth-grade science for a second. You might have learned that earthquakes are caused by the sudden movement of big, underground sheets of rock, called tectonic plates. Your teacher might have said they occur where two tectonic plates meet, at a fault line, as the plates slide against each other, separate, or converge.

So how did New York City and surrounding areas—which sit in the middle of the North American Plate and thousands of miles away from its edge—just feel an earthquake powerful enough to shake skyscrapers and bring recess inside at local schools?

Well, like much of the world after fifth grade, it’s a little more complicated than what you learned in school.

While earthquakes are most common along the fault lines of tectonic plates—of which there are seven major ones in the world—the seismic quakes can actually hit anywhere, at any time, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), a government agency that researches earth science.

Faults don’t just exist between major plates, but there are cracks or wrinkles within them, said James Davis, research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“It’s a place where earthquakes can happen if stress builds up, and stress can build up in the middle of a plate because of the forces of plate tectonics,” he told Fortune. “Take something and push it at the edges. The center can wrinkle.”

Per the USGS, the epicenter of Friday’s earthquake was Whitehouse Station, a town of less than 4,000 in northeast New Jersey—or just “west of Manhattan,” as New York Gov. Kathy Hochul posted on X, formerly known as Twitter. The town sits nearly 50 miles from Manhattan and above a system of faults, known as Ramapo Fault, that stems from the Appalachian Mountains and runs through Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and southern New York. The Ramapo Fault today produces relatively small quakes, and the last period of major seismic activity was around 200 million years ago, experts estimate.

New York City has its own share of faults (beyond the rats and street garbage problem). A series of small fault lines run underneath the city, one from west Central Park to east downtown and another crossing Harlem.

Friday’s earthquake was mild compared with some felt in California or the Caribbean, rating at 4.8 on the Richter scale. But “it’s pretty big for the Northeast,” said Joshua Russell, who teaches seismology at Syracuse University. It’s so big, in fact, that another of this size hasn’t reached the New York area in 140 years, Bloomberg reported. It also follows a much smaller one in January, rated a 1.7. The aftershock will likely last for the next couple of days, Russell told Fortune.

The earth’s crust is much older and more brittle on the East Coast, so earthquakes travel further and feel stronger than on the U.S.’s much more quake-prone West Coast, said Davis, the Columbia professor. Friday’s earthquake reportedly shook as far as D.C. and Canada.

“This earthquake will give us a chance to hopefully learn something,” said Davis, who felt the trembling from his home office in Rockland County, N.Y. “Is this part of a longer-term sequence of earthquakes? When we look at all the locations, do we see a pattern of where the biggest earthquakes occur? I can’t tell you what we’ll discover.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com