York County’s Black experience: From slavery to a history center telling their story

York County’s Black experience: From slavery to a History and Culture Center telling their story

York County’s Black experience: From slavery to a History and Culture Center telling this heritage

On a day long ago, a crowd outside the Boston Customs House brought snowballs to a gunfight.

Those well-aimed and tightly packed snowballs, of course, presented no match for the musket balls from the guns of British soldiers guarding the building on March 5, 1770.

Three in the crowd were killed immediately, and two among the eight wounded died later.

This was the first blood spilled in the American Revolution, and those slain are long remembered, particularly the first to die. Crispus Attucks, a freedman and sailor, would become the front man, the best known.

About 160 years later, in 1931, an organization designed to fight the uphill battle to provide social, educational and recreational services for York County’s growing Black population was founded and took on the name of African American martyr Crispus Attucks.

Ninety-two years after Crispus Attucks Community Center opened in the old York Hospital on West College Avenue, Crispus Attucks York will break ground for construction of a history and culture center. The event, open to the public, is set for 10 a.m. Nov. 15 on Crispus Attucks’ campus, 45 Boundary Avenue.

That groundbreaking date has a significant tie to the American Revolution, that eight-year war for independence that Crispus Attucks helped to inspire. Attucks and others that day in Boston were protesting British levies against American colonists. There was a big French and Indian War debt from the 1750s to pay, and the British were determined to make their American subjects fork over payment, even though the colonists had no representation in the matter.

That protest erupted in the American Revolution five years later. And a bit more than two years after that, America had declared its independence and adopted its first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, in York. That adoption date? Nov. 15, 1777.

That Nov. 15, 1777, and Nov. 15, 2023, linkage gives us an opportunity to briefly assess the lives and times of Black York County residents in the 1700s and early 2020s.

Those lives have taken on a decided upward arc, albeit with many ups and downs.

Settling York County

Enslaved Black people came to York County when European settlers started ferrying across the Susquehanna in some numbers after 1730. The bondsmen arrived with their masters chiefly from the east and south — and came in great numbers.

For example, Col. James Crouch moved to the Wrightsville area from Virginia about 1757 bringing 40 enslaved people with him. He married a local woman, and they had four children. Five years later, they prepared to move to Lancaster County. Two auctioneers were detailed to sell “sundry negroes,” livestock and plantation utensils tobacco and grain.

There was unending work to do in settling a well-watered land that measured at the time of its incorporation as York County in 1749 at about 1,500 square miles. That frontier ranged from the Susquehanna River to today’s Franklin County.

Vast forests needed to be cleared of great trees before the land could be tilled. And when the soil was tilled, the grain milled and livestock fed. Surpluses from the farm — meat, grain and distilled spirits — were transported to market on rutted roads in bad weather.

The extensive woodland fueled other enterprises. There were trees to fell and then converted to charcoal to fire forges that converted iron ore into cannonballs and stoves. At least five of these furnaces operated in the 1700s — industrial sites cropping up around a rapidly populating county.

And then there were towns growing around these mills, furnaces and crossroads. York was the largest, the market center, with tanneries and blacksmiths.

And as wealth increased, so did the size of houses. The wealthy needed help in the household and gardens.

In all these things — felling trees in the country and beating blankets in the towns — enslaved Black people contributed.

Tax records between 1765 and 1787 show that 30% of those operating local industries used enslaved people for labor and about one-third leased this labor when the need arose.

Indeed, in 1783, 520 enslaved Black people lived in 256 households in York County. Robert McPherson of Cumberland Township and William Cochran of Hamiltonban Township, both in today’s Adams County, were the largest holders of bondsmen with 11 each.

Enslaved people lived throughout the land but were particularly found in places where Scots-Irish farmed: the southeastern Peach Bottom/Chanceford Township region and the southwestern hinterlands, today’s western Adams County. The Scots-Irish also held a disproportionate number of the 68 indentured servants then in York County.

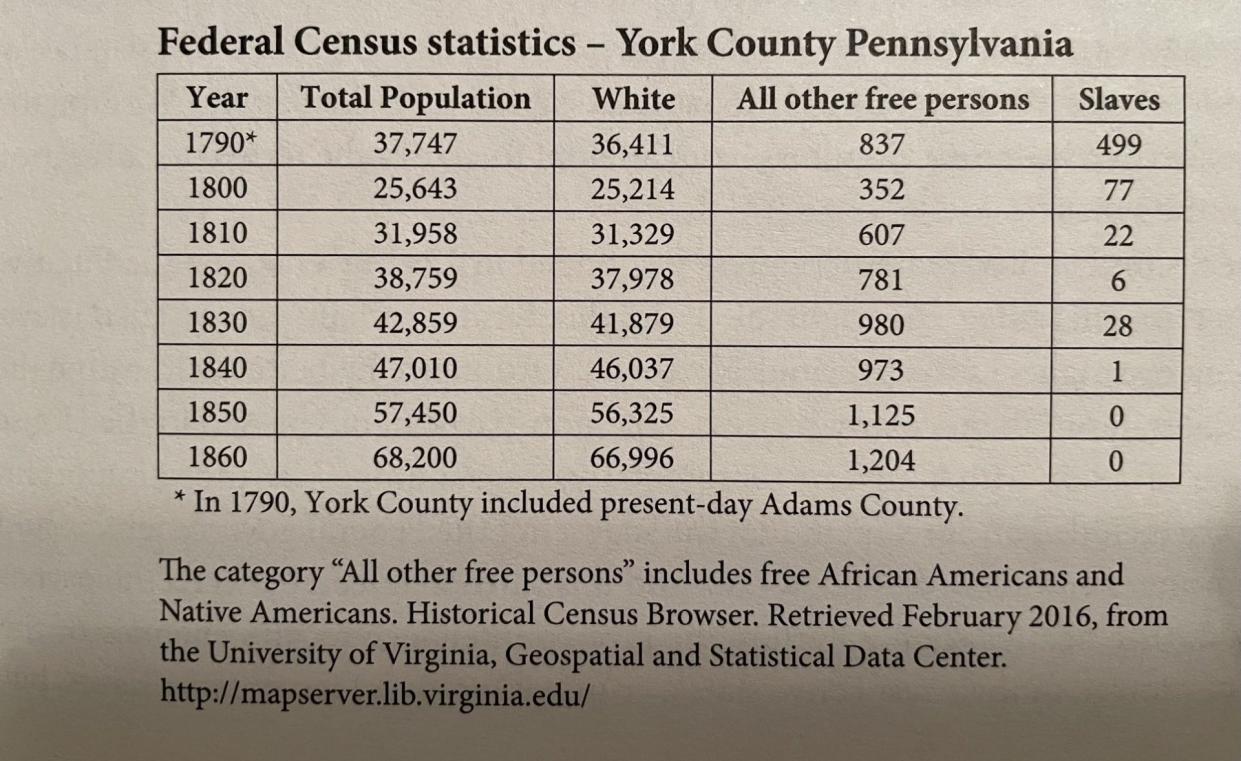

The number of enslaved people declined by the 1790 U.S. census to 499. To give those numbers context, York County residents held more slaves than any other county in the state in that census.

The 837 freedmen who lived here totaled second in the state to Philadelphia’s 2,102, indicating that many in York County had gained their freedom. We can make that observation because in 1780, Pennsylvania adopted a Gradual Emancipation Act that freed bondsmen in the state when they reached age 28. The law also required owners to register their enslaved people, and failure to do so meant freedom of their bondsmen.

The sad fact is that York County, as elsewhere in the state, was in the emancipation and bondage business at the same time. The 1840 census lists one slave held in York County, and slavery had ended by 1850.

Freedom is everything

Some might argue that in such a rich land as York County — with its limestone soil and rolling hills divided by streams — enslaved people benefited from this largess. This is a similar argument later used to say that conditions for enslaved people in the antebellum Upper South weren’t as bad as that experienced in the Deep South.

But a fact overlooked by those suggesting chattel slavery wasn’t really that bad is that when you don’t have freedom, you don’t have anything.

And the second part of that is that slavery in York County and elsewhere carried with it patent racism. The people enslaved in America in the late 1700s were Black. Even white indentured servants could gain their freedom.

So freedom is everything, a tenet held by another group temporarily living in York County in the 1770s: the Continental Congress.

The presence of slavery in the 13 states was part of the personal and legislative lives of many of the 64 delegates who met in York for nine months. South Carolina’s Henry Laurens, for example, conducted business from York concerning enslaved people on his plantations. North Carolina delegate Cornelius Harnett placed a notice in the Pennsylvania Gazette, published in York, for the return of his freedom-seeking bondsman Sawney.

And politically, Congress debated whether assessment to states for war costs should be based on private property or by head count. A per capita assessment, akin to what was written in the Constitution a dozen years later, would have strengthened the institution of slavery in the Articles of Confederation.

When the Articles were adopted on Nov. 15, 1777, many could see a path to freedom from Britain for white Americans. Because France needed a constitution ensuring that the 13 states could work together, it came on board as an ally.

From low point to high

When you add it up, York County in the 1700s was heavily invested in slavery.

That is the starting point, a low point, in the lives of Black people in York County. There would be others: in the race riots-torn 1960s, for example. And today, large income and homeownership disparities remain among the white population and Black and Latino people in York County.

Still, an upward arc can be seen for Black people in the county. After the disruption of riots in 1968-69 and subsequent community gathering called the York Charrette, Black people slowly gained traction in the county.

Crispus Attucks York became a prime influencer in that regard after Ray Crenshaw and Daniel Elby asked Bobby Simpson to come onboard to lead the organization in 1979.

Simpson became the first Black York County Chamber of Commerce and York College board member. Elby was the first Black person to sit on WellSpan’s board. Crenshaw became the first Black person to run for York mayor.

Earlier, Roy Borom, Crispus Attucks’ executive director, became the first Black York City Council member. Frederick D. Holliday, Simpson’s mentor, served as York city schools’ first Black superintendent

On Nov. 15, 2023, Black leaders at Crispus Attucks York in breaking ground for a History and Culture Center will be in the vanguard of shoveling the same ground as their forebearers. These Black leaders will be digging shiny silver ceremonial shovels into the soil that their ancestors tilled using rudimentary tools for survival.

This comparison is a testament to perseverance as Black people fought to rise in that uneven arc from slavery to create a gleaming museum and cultural place in which their story will be at the center.

Sources: YDR files, Scott Mingus’ “The Ground Swallowed Them Up,” David Latzko’s “Ethnic and Economic Diversity in York County at the end of the Revolutionary War,” Journal of York County Heritage, 2020, YorkCounts.org, Library of Congress.

Upcoming event

York County History Storytellers will host an evening in which local histories present about “Champs and Foes” in the county’s past. It’s set at 7 p.m. Dec. 7 at Wyndridge Farm near Dallastown. Ticketing and details: www.yorkhistorycenter.org/event/history-storytellers.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: The Crispus Attucks History and Culture Center breaks ground Nov. 15