Writing Through the War in Ukraine

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

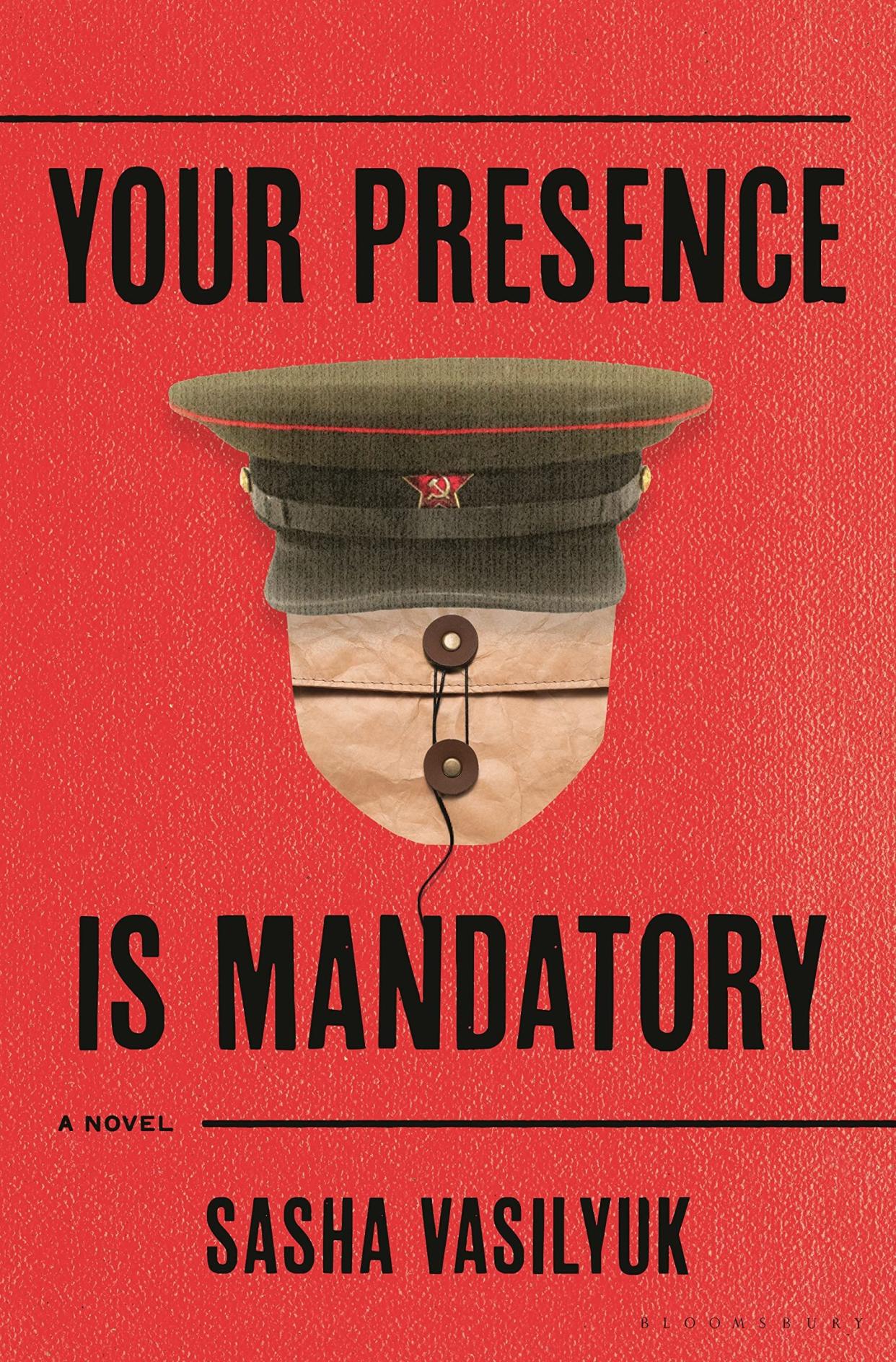

Two days after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Sasha Vasilyuk published a wrenching op-ed in the New York Times titled, “My Family Never Asked to Be ‘Liberated.’” In the essay, she recounts urging her 90-year-old grandmother, a survivor of the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, to leave the sieged city of Donetsk. “Let them come and get me. I’m too old to leave,” her grandmother replies, before reciting an obscene poem she’d composed about Russian president Vladimir Putin. Ever since, Vasilyuk has been a pre-eminent critical voice on the collateral damage of Russia's war on Ukraine. Her journalism, which uses family history as a lens into the war, captures the minutiae of how it feels to be living in historic times. Her debut novel, Your Presence Is Mandatory, is somehow even more gripping, flawlessly melding a page-turning fictionalization of true events with a darkly comic voice.

Your Presence Is Mandatory follows Yefim Shulman, a Ukrainian Jewish World War II veteran with a terrible secret. After being captured by the Hitler’s army, he does what he must to survive, and spends the rest of his life concealing his past from his family. Days after his death, his widow discovers a shocking letter addressed to the KGB, begging them not to reveal the truth to his family. But the novel is so much more than an account of how Yefim spent the war. It’s a clear-eyed portrayal of how borders move through us, and how surviving war entails enduring many deaths, large and small, within the self.

You might be wondering, where does the comedy come in? Anyone who has spent time with post-Soviet Jews knows that dark humor is one of our go-to coping strategies (shame is the other, but we’ll get to that). Forced into a factory job processing metal parts for the German army, Yefim thinks, “Nothing made with such precision was going to be used for bicycles.” Your Presence Is Mandatory is full of spiky details that stuck with me—or, more accurately, stuck to me—long after I reached its haunting modern-day conclusion.

Vasilyuk is uniquely qualified to tell this story. Yefim is inspired by her own grandfather, who harbored the same shocking secret all his life. Her family encountered a similar letter addressed to the KGB after his death and was left to process the aftermath of his concealment without him. A few weeks before publication, Vasilyuk spoke with Esquire about how her grandfather’s secret influenced her novel, the ethics of fictionalizing trauma you didn’t personally experience, and finding humor in the direst of circumstances. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: Your novel is inspired by a family secret of your own. Shortly after your grandfather died, you discovered a confession letter he’d written to the KGB. What did the letter say?

SASHA VASILYUK: Grandpa was a Jewish Ukrainian WWII vet who never talked about the war, but we always assumed he was a war hero because he fought against Hitler’s army the entire length of the war, which was extremely rare. But in the ‘80s, the KGB discovered that he’d falsified his war record and demanded an explanation. The confession letter we found reveals that his wartime past was much less him kicking Nazi German ass (cue Inglourious Basterds soundtrack) and much more The Pianist, if Adrien Brody’s character also had to hide his survival. The letter is very short and, as confessions in totalitarian regimes go, isn’t exactly steeped in true emotions. Except for one telling sentence, where he begs the KGB not to tell the truth to his family because “it would be a big psychological trauma” for us to find out about his past.

amazon.com

$26.09

And was it a big psychological trauma?

The letter was definitely a shock for all of us, but it wasn’t the trauma he’d imagined. Mostly we felt sympathy and regret for not having asked him enough questions. For letting him live in fear that we would judge him.

How did the contents of that secret letter influence Your Presence Is Mandatory?

The letter was the seed for the novel. I wanted to dig into what had kept him silent, but when I began researching it, I realized that my grandpa’s story was both unique and reflected the fate of millions of people who’d also hid their past. I had huge gaps in my understanding of WWII and of Russia’s history, which I think is a common experience of people coming from a secretive regime. That’s why the oral history work of Svetlana Alexievich has been so important and eye-opening.

You’ve been a pre-eminent critical voice on the collateral damage of Russia’s genocidal war in Ukraine. How did the timing of the war intersect with your work on the novel? Did your Ukrainian family’s experiences in the last few years influence where you took the novel?

Though I had the letter, I didn’t feel super confident writing the story of a Soviet WWII soldier. This was back in 2007, when the idea also didn’t feel urgent. Though WWII still looms very large in Eastern Europe and arguably Europe as a whole, I didn’t feel that this story would translate to the U.S. Then, in 2014, Russian-backed separatists incited a coup in my family’s hometown in the Donbas, basically in front of my grandparents’ apartment. Soon, there was shelling, and I kept begging my 90-year-old grandmother to leave, to which she calmly replied that having survived the Nazis, she wasn’t leaving her comfortable bed because of some Russian scum. She and my aunt kept repeating, “Thank God your grandpa isn’t here to see this,” meaning that having survived one war, he would be horrified seeing another.

There were these constant links they made between the two wars. In 2016, when it was deemed more or less safe, I traveled to the Donbas, where I discovered that the clock had been turned back by a few decades. The streets, where bullet holes riddled almost every surface, were full of these bizarre Soviet-looking posters of soldiers saving grateful children with Russian insignia in the background. Cars had WWII victory signage and bumper stickers that said, “We made it to Berlin. We can do it again if needed.” It felt like WWII and the Soviet era were literally everywhere. The messaging was: Russians are fighting Nazis and will be victorious just like last time. After seeing how war and propaganda go together, I felt compelled to write a novel that weaves the two wars together through one family’s story. I wanted to resurrect the silenced past of my grandparents to contest this new, aggressive re-appropriation of history.

Pozor—shame—is a huge part of post-Soviet inheritance. I’m part of a private online community of progressive Soviet emigrées that’s something of a support group for unlearning the internalized shame that dominates so many of our lives. Many of us are in our thirties, forties, fifties, and up, and still struggling with the feeling that disgracing our community is a medical emergency. I myself was very anxious about how my immigrant community would react to my sexually explicit, queer as fuck, druggie novel. Has that been your experience at all? How did writing this book play into that?

Oh my god, how do I get invited to this group? I have to confess that I was also worried about how your parents might react to the hot, druggie explicitness of All-Night Pharmacy. I’m impressed by your ballsiness!

In my case, I was surprised to find that, for a long time, I didn’t want to tell my grandpa’s story to my childhood friends from the former Soviet Union. It was as if I’d subconsciously internalized his shame. Which I think speaks to how deeply shame is embedded in our Soviet upbringing. While researching the book, I realized how common this feeling was. Writing this book became my way of processing that shame. Though, honestly, a small part of me still worries that some crazy Putin-loving Russian will say, Oh look, her grandpa sat out the war and she is writing about it. Pozor! Disgrace!

Since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, I also struggle through feelings of shame for Russia, where I spent a part of my childhood. And, unlike the artificial Soviet shame, the shame of starting a war is very legitimate, very painful, and will be very hard to shed.

I know what you mean. My brother and I recently rewatched one of our favorite Soviet cartoons from childhood, The Bremen Town Musicians, which I associate with pure joy. My baby was crying, and we played her the soundtrack as a distraction. But the lyrics hit different in the wake of the war. My favorite song—about the irreplaceable value of freedom and seeing any place you roam through as home—suddenly felt so insidious when sung in Russian. This is, of course, the smallest of potatoes in terms of the downstream effects of the war. But that pain is real too. And a novel can be just the right container for it.

Isn’t it interesting how the meaning of innocent things changes with a new context? My daughter and I recently heard a Soviet-era song that goes, “In our country, everyone is friends. We do not live for war.” It struck me as so bitterly ironic. It also made me realize how formative that rhetoric of brotherhood, peace, and freedom was in our upbringing. And how painfully false it now seems. And yet, do I want my 3-year-old to believe that everyone is friends and we do not live for war? Heck yes.

I find the topic of reinterpreting the past very interesting in my writing, in my own life, and in what I like to read. I’ve always loved novels that trace the effects of something very dramatic or traumatic on someone’s entire life or across multiple generations. Like Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing or Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex or Updike’s Rabbit novels. They all have this continuity where the past keeps informing the present. In Your Presence Is Mandatory, I loved playing with seeding moments, hopes, secrets, and then, a few chapters-slash-years later, showing how they’ve bloomed.

I would be so intimidated to write a novel like yours, which clearly necessitated a deep grasp of history. I imagine your background as a journalist made you especially equipped to translate how it might have felt to live through the historic times you write about. What kind of research did you do?

As a journalist, I was used to relying on firsthand accounts, but my grandparents were both dead by the time I sat down to write this book. Still, I was determined to make this novel as realistic as possible. Yes, it’s fiction, but I felt I owed it to the survivors to show the real drama of their experience, which was honestly more mind-blowing than anything I could have invented. Sleeping standing up under the rain in a prisoners’ camp is not a detail I could have imagined. And yet, it’s what happened. Luckily, my grandma wrote a memoir and because she had an elephant’s memory, parts of it—domestic details, popular jokes, smells, love drama—were extremely useful. I couldn’t find details like that in history books. I also read books about Soviet prisoners of war and Jewish soldiers, and I listened to a podcast that interviewed Soviet forced laborers who’d been deported to Germany. Most of these people had kept quiet about their experience until very late in life, precisely because of that shame we discussed.

Your grandmother wrote a memoir! Did it address your grandfather’s secret? I must know more.

Interestingly, not really. Partly because she wrote some of it before he died. Still, I expected her to address it in the portion she wrote (or rather, dictated) after he passed. But I think she was too involved in telling her own story. After surviving all kinds of crazy Ukrainian things (famine, war, being orphaned, etc.), she became a renowned paleontologist, so a lot of her memoir is about the conferences she traveled to and how her jokes slayed at work parties.

That “etcetera” after “famine, war, being orphaned,” made me cackle. Whenever I interview a post-Soviet Jewish writer, I can’t resist asking about our people’s particular brand of dark humor. I laughed out loud at deadpan lines like, “She told herself she couldn’t blame Claudia for stealing her husband, given how few healthy men were left after the war.” Was humor something you consciously tried to steep the novel in, or was it inevitable?

Honestly, I wish I was better at writing humor, because I feel like I’m much funnier in person than on the page. My grandparents both had this very quirky, irreverent sense of humor that was steeped in living in a place where you couldn’t publicly say what you thought. Comedy culture is a huge part of living in the constant shitstorm that is Eastern Europe. Look at Volodymyr Zelenskyy—a comedian turned Ukrainian president. Whenever I call my aunt in Ukraine, she cracks a joke, even though the woman has been living with shelling for 10 years and just survived a dire cancer diagnosis. Still, she jokes. So, yes, I did consciously work in humor when I could. Humor feels especially poignant in the darkest moments.

My novel, like yours, borrows from family lore that I wanted to memorialize, lest the oral histories get lost. But doing so is fraught for me. I see myself as a cultural custodian trying to honor those who came before me, but there’s a more cynical way of looking at it too—that I fictionalized family traumas I didn’t personally experience to sell books. Is this something you struggle with?

I look at it more as a journalist delivering a story that would otherwise not exist. Barely anything has been written about the millions of people like my grandfather. The government hid their stories and silenced them. And now, Putin is trying to further erase any history that doesn’t suit his vision. So, no, I don’t feel like I’m fictionalizing trauma to sell books. If I didn’t write this story, the suffering of survivors like my grandparents would have been for nothing, and the narrative of the men like Stalin and Putin would have won.

You Might Also Like