‘Worse than the South.’ Remnants of housing discrimination linger in Eastern WA

There was a time in the Tri-Cities when no Black person lived in a house in Richland.

In Pasco, almost every Black and Asian American lived east of the railroad tracks.

Streets there were dirt, they had no indoor plumbing and water had to be carried from communal pumps.

Kennewick was a sundown town.

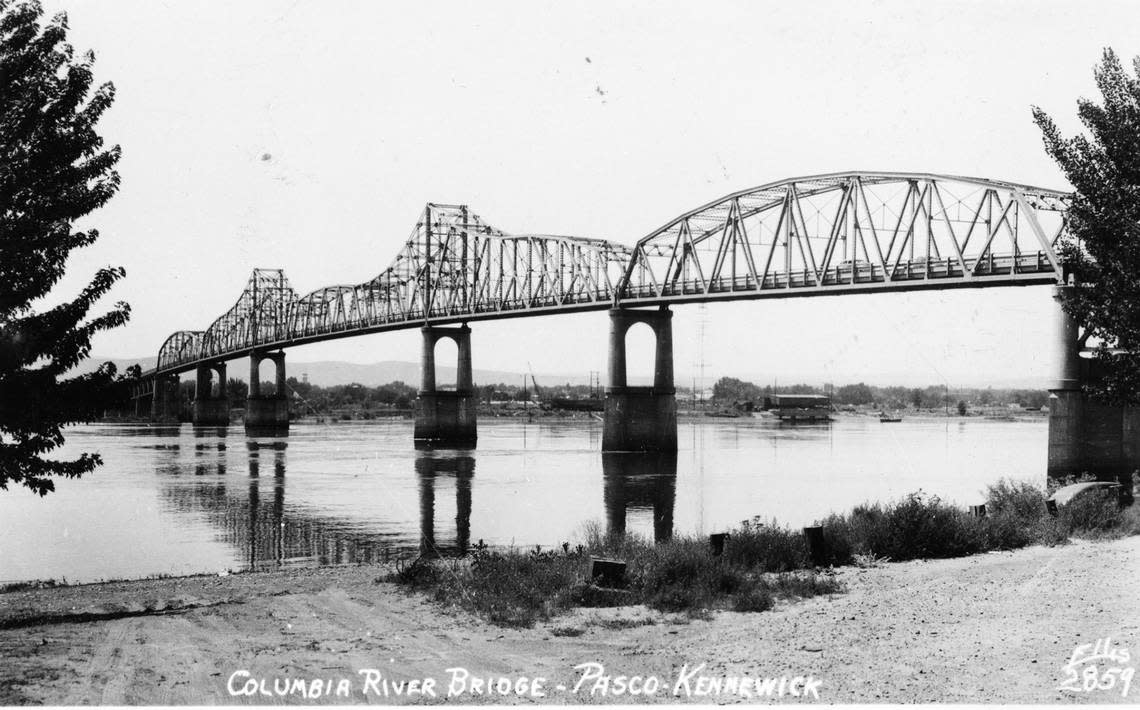

A sign on the former green bridge between Pasco and Kennewick warned that Blacks were banned from Kennewick after dark.

Residents were so determined to keep Blacks from living there that when Kennewick police stopped David Raines’ cousin “on account of him being Black and riding in the car” between two white men, they wouldn’t even take him to jail, Raines once told the Herald.

Instead, they tied the Hanford construction worker to a power pole and called Pasco police to come and get him.

What Tri-Cities residents may not realize is that they still may be living in a neighborhood that prohibits Black residents.

Starting in the 1940s, racial covenants, or clauses, were inserted into property deeds as one way to keep anyone who was not white from buying a home or property in Kennewick and Pasco.

Now a statewide initiative is underway to identify all property records with racist restrictions.

So far than 1,400 properties have been identified in Benton and Franklin counties with racially restrictive covenants, with research to find more continuing.

Those initial results for the Tri-Cities reflect its fraught racial history.

WWII escalates Tri-Cities segregation

The Tri-Cities missed the first wave of the great migration of Blacks from the South from the teens of the last century through just after World War I, says Robert Bauman, a history professor at Washington State University Tri-Cities.

Pasco, Kennewick and Richland were just too small and Blacks migrating to the Northwest then settled mostly in Seattle and Portland.

Before WWII only 27 Blacks lived in Pasco.

But the secret WWII project to produce plutonium for the atomic bomb changed that.

DuPont needed to fill as many as 53,000 jobs to build and staff the Hanford site facilities that would produce plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

About 15,000 Blacks arrived in the Tri-Cities from 1943-’45, mostly recruited from the South, as Bauman wrote in “Jim Crow in the Tri-Cities, 1943-50,” a paper published in the Summer 2005 Pacific Northwest Quarterly.

Other Blacks came to work at the Pasco Naval Air Station during WWII.

That migration of Black workers was not the start of racial discrimination in the Tri-Cities.

Pasco began as a railroad town and the non-white community, including a few Black families and Japanese and Chinese families, mostly lived east of the railroad tracks in Pasco.

But with the influx of Black workers during the war “a system of segregation was put in place really quickly, almost over night,” Bauman said.

The military was segregated during WWII, and Hanford was a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project.

Hanford, a segregated site

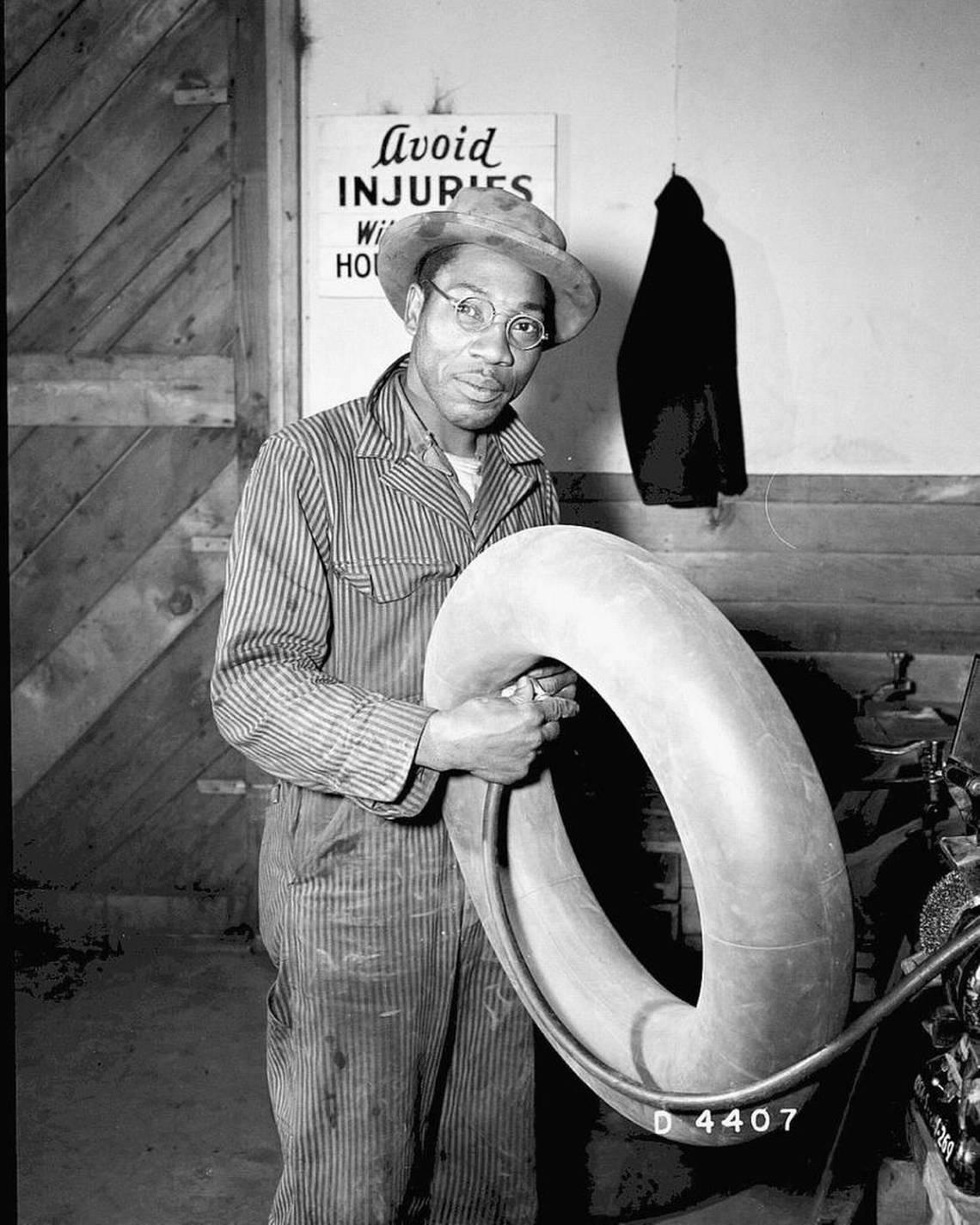

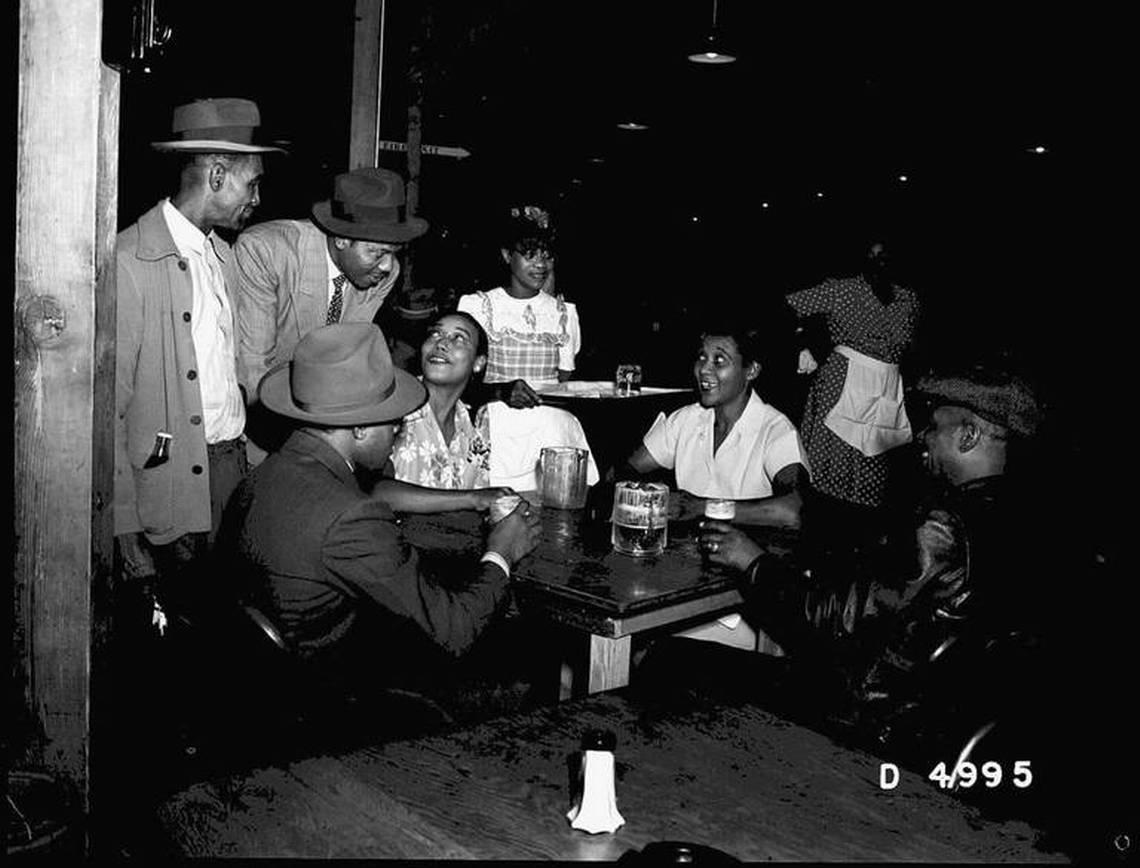

Hanford had not only separate barracks for Black workers, with husbands and wives living in different dorms, but they were restricted to a segregated commissary and tavern, dining hall and church services.

When more housing was needed for Black workers beyond the barracks at the construction camp built on the Hanford townsite, DuPont negotiated with Pasco to put one barrack and one bunkhouse in east Pasco for Blacks.

Before the war was over, a less desirable part of what was then the largest trailer park in the world was opened to Black workers and their families.

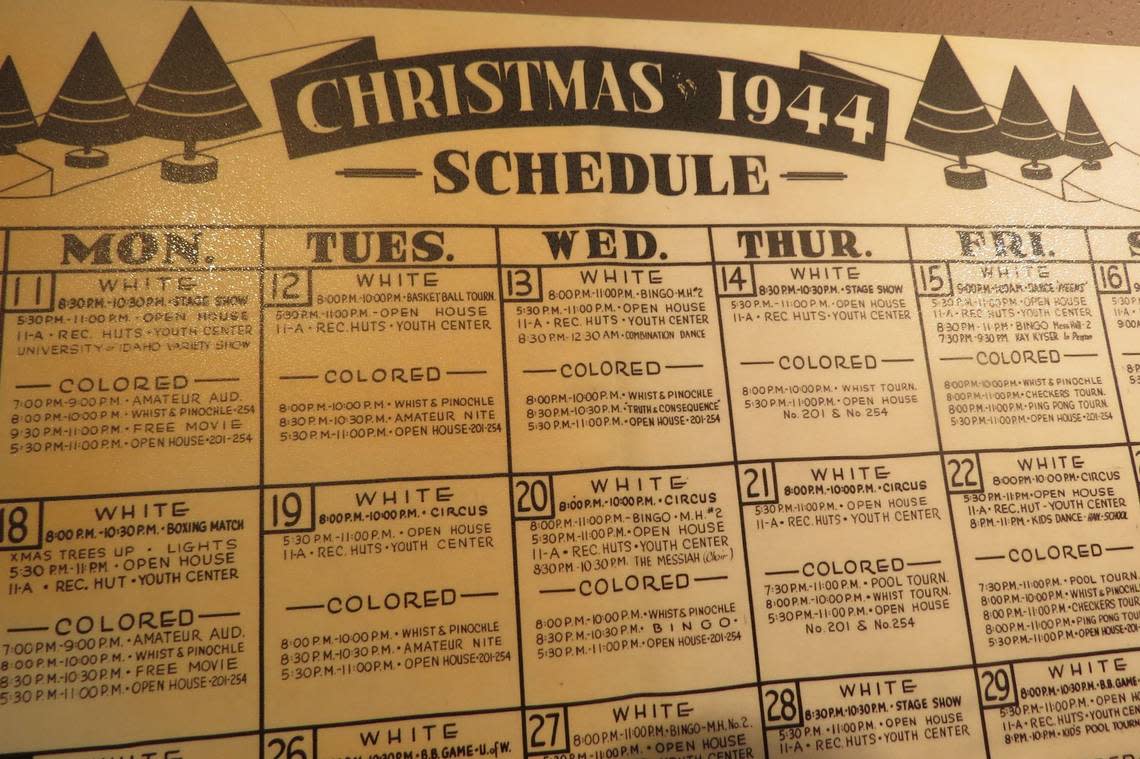

Entertainment opportunities at Hanford were not only separate, but also unequal.

In 1944, desperate to retain its homesick work force, DuPont planned a month-long schedule of Christmas and New Year’s entertainment. Each day featured entertainment listed under a calendar as for “white” and “colored.”

On Dec. 28, a stage show was organized for whites and a card tournament for Blacks. On New Year’s Eve, a dance featuring “King” was the highlight for whites. Blacks were offered Bingo, a ping pong tournament and a general party.

As Richland was expanded into a planned government community for Hanford workers, houses were built. But not for Black workers.

Only permanent workers were allowed to live in Richland houses.

That excluded Black workers who were only hired for construction jobs and jobs such as cleaning and serving and cooking for dining halls. Those were considered temporary jobs.

Most Black Hanford workers left the Tri-Cities as the war ended, and with it most construction jobs at Hanford, Bauman said.

Then Washington Gov. Arthur Langley had told Hanford commanding officer Col. Franklin Matthias that he hoped “arrangements can be made to return most of the construction workmen back to their original centers of activities, particularly the Negroes.”

It wasn’t until the Cold War began that a new wave of Black residents moved to the Tri-Cities to take permanent Hanford jobs.

In 1950 just seven Blacks lived in Richland, according to his Pacific Northwest Quarterly article.

The first post-war contractor at Hanford, General Electric, was pressured in the early to mid ‘50s by civil rights organizations and the NAACP National Urban League to hire Black employees for white-collar jobs, Bauman said.

In 1958, Richland gave up its status as a federally owned town, and residents were allowed to buy the government houses there. But buying a house there remained difficult for Blacks.

CJ Mitchell reported in oral history projects for both the Atomic Heritage Project and the Hanford History Project before his death that when he came to the Tri-Cities in 1947 as a recent high school graduate he slept in a tent in east Pasco and then moved to Hanford’s segregated barracks.

He tried to buy a house in Richland for his family in 1965, but was told the house he wanted in Beverly Heights, up the hill from Fred Meyer, was not for sale to a Black family, he said in an interview for the Hanford History Project.

“In 1976, when I moved to where I am now, when I moved in, the next night, I got a phone call that said, ‘This is the Ku Klux Klan, and you’re next.’ I’ve gone through all of that,” he said in his oral history for the Atomic Heritage Project.

Pasco housing discrimination

As the Black population began to increase during WWII, signs started popping up around Pasco saying, “No colored businesses solicited,” or “We are open for white trade only,” Robert Franklin, a WSU Tri-Cities assistant professor, wrote in “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance,” a book edited by Bauman and Franklin.

Although Blacks could make their home in east Pasco, they largely were not welcome to shop or eat out west of the railroad tracks and often traveled to Yakima for basic services, including medical care, by Franklin’s account.

That was a change from the pre-war years when few Blacks lived in the Tri-Cities and could generally eat and shop where they wanted in Pasco.

The Lewis Street underpass was the unofficial dividing line that separated Pasco during the Manhattan project, according to the National Park Service.

East Pasco, where Blacks were relegated to live, was nothing like the rest of Pasco.

Homes were made of shacks, converted chicken coops and old trailers.

Residents carried water from a few community taps and used outhouses. Streets were unpaved and unlighted, according to “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance.”

In 1948, a Washington State College study found that 6% of white families in Pasco lived in one room, but 78% of Black families lived in one room, according to Bauman’s paper in Pacific Northwest Quarterly.

By 1950, Pasco’s population was 20% Black, the highest per capita in the entire Northwest, according to Bauman and Franklin’s book.

But it wasn’t until the mid to late ‘50s that east Pasco had full sewer service, according to their book.

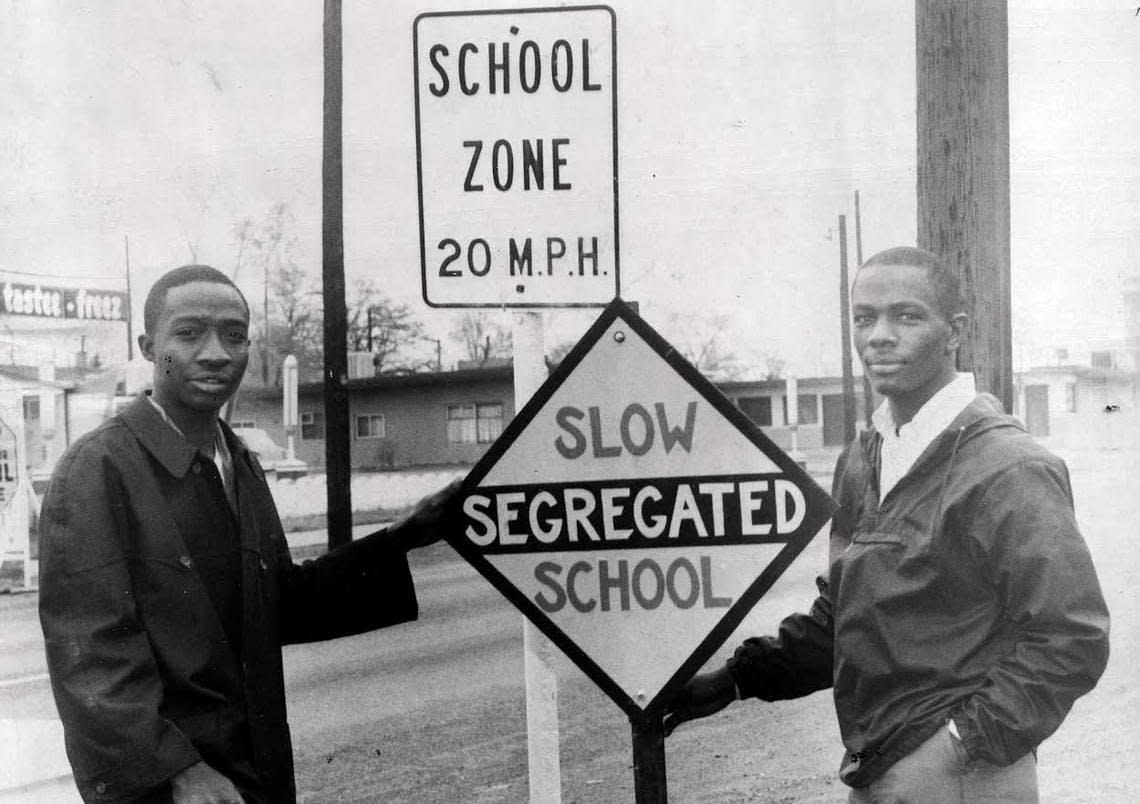

Kennewick ‘sundown’ town

While Pasco was trying to confine Blacks, Kennewick was trying to exclude them, according to the National Park Service.

Kennewick prided itself on being “lily white,” Bauman said.

Police would routinely stop Blacks passing through, according to the park service.

It quotes Katie Barton, who moved to the Tri-Cities in 1949, as saying, “You couldn’t buy a house there; you couldn’t go to the movies there; they wouldn’t put you in jail there. [The] Tri-Cities was worse than the South ever was because you knew where you stood there. But you didn’t know here you stood here.”

Racially restrictive housing covenants and other means were used to keep Blacks from moving into Kennewick for decades, Bauman said.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that racially restrictive housing covenants could not be enforced, they were replaced by voluntary agreements between real estate agents and homeowners to refuse to sell or rent to Blacks, Bauman wrote in Pacific Northwest Quarterly.

Blacks also were hesitant to move to Kennewick given the town’s reputation, Bauman said.

Bauman and Franklin wrote in “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance,” that in 1961 a young Black couple inherited a Kennewick house from friends of their family.

Shortly after the daughter and son-in-law of Cornelius Walker moved in, it burned down while they were visiting Walker in Pasco. Arson was suspected but never proved, according to Bauman and Franklin.

In 1964, a Black family became the first to rent in Kennewick, following a targeted campaign by the Tri-Cities chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality.

CORE member Nyla Brouns, who was white, went with Mary Slaughter to look at a house to rent. Only when the landlord agreed to rent the house did Brouns turn to Slaughter, who was Black, and ask if she thought the house would do for her, according to Bauman and Franklin’s book.

When another Black couple, Herb and Rendetta Jones, moved to Kennewick in 1965, the tires of their new Ford were slashed and the windows broken. Rocks were thrown at the house.

CORE members would drive immediately behind Rendetta Jones as she went to and from work to protect her from any violence.

From the 1940s to the 1960s the Washington state Board Against Discrimination came to the Tri-Cities multiple times in response to complaints of segregation, Bauman said.

After one hearing of the board in 1963, local residents demonstrated for civil rights.

Bauman and Franklin’s book describes 74 people led by the president of the NAACP state chapter marching through the streets of Kennewick holding signs that read: “The South has no monopoly on bigotry” and “Why is Kennewick all white!”

Wally Webster in an oral history for the Hanford History Project described another march over the green bridge from Pasco to Kennewick to where cars with rebel flags were racing their engines on the Kennewick side of the bridge.

It wasn’t until the late ‘60s and ‘70s that Kennewick changed, a result of pressure from civil rights groups and the state board, plus likely a change in people in position of power, Bauman said.

Police appeared to harass Blacks less often and a small number of Blacks began to move to Kennewick.

In 1968, after a failed attempt four years earlier, Richland passed one of the most comprehensive open housing ordinances in the nation, according to “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance.”

It came on the heels of controversy over a Mid-Columbia Symphony Guild fundraiser ball planned for the Pasco Elks Club, which then did not allow Blacks to join, the book said.

Improvements in east Pasco were slower to come.

Eventually, 78 homes were destroyed in the interest of “urban renewal,” in Pasco. Just eight were rebuilt, according to Bauman and Franklin’s book.

As Latinos began to arrive for agricultural work in the Tri-Cities in the 1970s, they also faced initial housing discrimination and were steered toward east Pasco, according to “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance.”

“The racial scripts related to housing in Tri-Cities continued to impact nonwhites into the 21st century,” Bauman and Franklin wrote.

To learn more

To learn more about the racial history of the Tri-Cities, “Echoes of Exclusion and Resistance” is available at Mid-Columbia and Richland libraries or for purchase from wsupress.wsu.edu.

Franklin will discuss “The History of African American Segregation and Resistance” and answer questions about Hanford and the Tri-Cities in a talk for the Washington Department of Ecology.

It will be streamed on the Washington Department of Ecology Hanford Facebook page and on Zoom at 5:30 p.m. Feb. 28. Information for joining the Zoom session is posted at bit.ly/HanfordBlackHistory.