Workers most exposed to AI bet it will help — not hurt — them, study finds

Workers most at risk of being replaced by AI feel the least threatened by it, according to a new study.

The report, released by the Pew Research Center this week, shows that a fifth of workers have high exposure to artificial intelligence, meaning their job duties have a high likelihood of being aided or replaced by AI. But more of those workers are betting the technology will help them, not replace them, the study also found.

The study takes an educated guess about which workers are most likely to use AI in their jobs amid uncertainty about how the workforce will evolve. It also reveals broader attitudes about the technology as it increases in prevalence.

“As we know, AI could either help with or replace what workers do on their jobs,” said Rakesh Kochhar, the author of the report. “This finding from our survey suggests that workers with more exposure to AI, at least for now, are seeing it as more helpful than hurtful, providing context to the debate over the likely impact of AI in the future.”

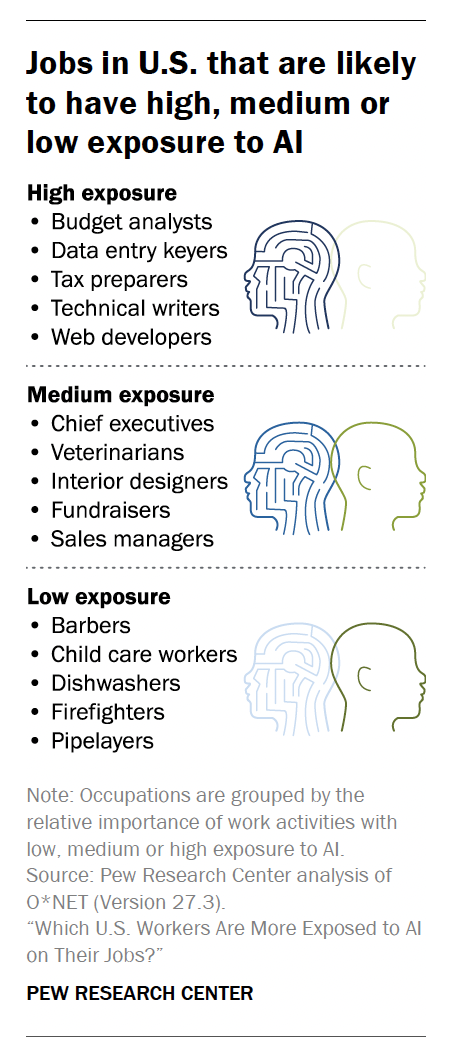

The study released by the nonpartisan fact tank in Washington, D.C., used the Current Population Study from the Census to examine 41 work skills associated with job performance and categorized them into three categories including low exposure, medium exposure, and high exposure to AI. The report also surveyed 11,004 US adult workers in December to glean their attitudes toward AI.

“How we rank activities, worker-related activities by their exposure to AI is based on a collective understanding of what AI is capable of doing right now,” Kochhar said. “We know that AI is not capable of going in and repairing your car at the moment — not by itself. But we know that AI is capable of writing software that is capable of searching for information on the internet.”

The study found that 19% of workers were in jobs that were the most exposed to AI, including budget analysts, data entry keepers, and tax preparers. Meanwhile, it ranked veterinarians, interior designers, and fundraisers as medium exposed. Some of the least exposed professions included barbers, childcare workers, and firefighters.

The study distinguished between analytical jobs — which require creative thinking, mathematics, or science — and mechanical ones, which require more physical skills like carrying objects or repairing machinery and equipment, Kochhar said.

“So we found a fairly clear relationship between analytical skills that workers are required to have on a job and the kind of activities they do on the job and their exposure to AI,” he said.

The study also found that specific demographics are more likely to be exposed to AI.

For instance, workers with a bachelor's degree or higher were more than twice as likely to work at jobs that saw exposure to AI. Workers who earned more were also more likely to have exposure to AI, with those in the most exposed jobs earning $33 per hour on average versus those with the least exposure making $20.

Also, women were more exposed, with 21% having occupations that risked exposure to AI versus 17% of men.

That doesn’t mean these specific jobs or their workers would be completely replaced by AI, Kochhar pointed out.

“We are not talking about job losses. We're talking about people who in their job are likely to be exposed to AI meaning they perform work activities that AI may even help with,” he said. “Or, it might replace them. We don't know yet how AI itself will be applied on the job.”

The study’s respondents also appear to be more optimistic about how AI could assist them.

For example, 32% of information technology (IT) workers said that AI would help more than hurt them personally, as opposed to 11% who said it would hurt them more than help. Additionally, 26% of participants who held jobs in professional, scientific, or tech services also said the nascent technology would help them versus 14% who said the opposite.

Kochhar said workers in such fields might feel secure in their jobs because they are more familiar with AI than workers in other industries.

“Workers who are seeing more exposure are more familiar with what AI can or cannot do,” he said. “And whereas other workers were less exposed or feeling greater uncertainty because they're just not exposed to the technology.”

Giacomo Santangelo, an economist at Fordham University and the recruiting company Monster, added that these workers might see AI as an opportunity to gain skills that increase their job security. Santangelo, who was not affiliated with the study, said that higher-paid workers often have the time and confidence to acquire new skills.

“It’s going to be easier for someone in the C-suite to acquire additional skills to get that additional training,” he said. “They don't have to worry about the fact that if they take an extra hour at lunch to do one of the online courses with one of multiple different companies that train in this that it's going to affect their income.”

He also said these workers might appreciate the business benefits of AI, drawing a comparison between nascent AI technology and computers. For instance, when corporations began using computers instead of typewriters, employees with information systems training were able to acquire new skills and recognize the “potential cost-cutting benefits” of the technology, Santangelo said.

But for every cost-saving computer boosting employee productivity, there are examples of other technologies — such as digital automation beginning in the 1980s — replacing workers like production and clerical workers.

From the 1950s until the 1980s, technology created new jobs at the same rate it destroyed them, according to research by Pascual Restrepo and Daron Acemoglu. But starting in the 1980s, that changed. Joe Briggs, an economist from Goldman Sachs, speculated that AI could destroy more jobs than it creates.

“For most of post-war US history, jobs were created and jobs were destroyed at roughly the same pace by technology,” Briggs said. “Starting in the 1980s, you saw this shift a little bit where the rate of displacement picked up and actually exceeded the rate of reinstatement or the rate of new job creation … I do think that there's a risk that sort of AI as a technology looks more similar to the IT experience than it does prior technology waves.”

Still, Briggs harbored uncertainty with respect to the future of AI and the workforce. Kochhar agreed, despite the more optimistic results of the study.

“The main takeaway from this particular study is that AI is likely to have a varying impact on different groups of workers,” he said. “We know that it is, in some fashion, disruptive. We don't know overall if it is good or bad, or overall creates more jobs or ends up cutting more jobs.”

“We just don't know that yet.”

Dylan Croll is a Yahoo Finance reporter.

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance