‘Word of mouth.’ How underdog Democratic candidate Willie Rowe won Wake sheriff’s race

Willie Rowe fought the odds to become Wake County’s next sheriff against a challenger who had name recognition, a lot more money and had held the job before.

Rowe, a Democrat, defeated Republican opponent Donnie Harrison in the Nov. 8 election with 53% of the 445,972 votes cast, according to unofficial results reported Tuesday.

The race was expected to be an uphill battle for Rowe, 62, who was not as well-known as his opponent.

Harrison, 76, was sheriff for 16 years and was a state trooper in Wake County before that. He also had previously beat Rowe in the 2014 election, Harrison’s last electoral victory.

But the friendships and relationships that Rowe maintained since then paid off, many of them created throughout his previous 28 years working in the Sheriff’s Office, he told The News & Observer.

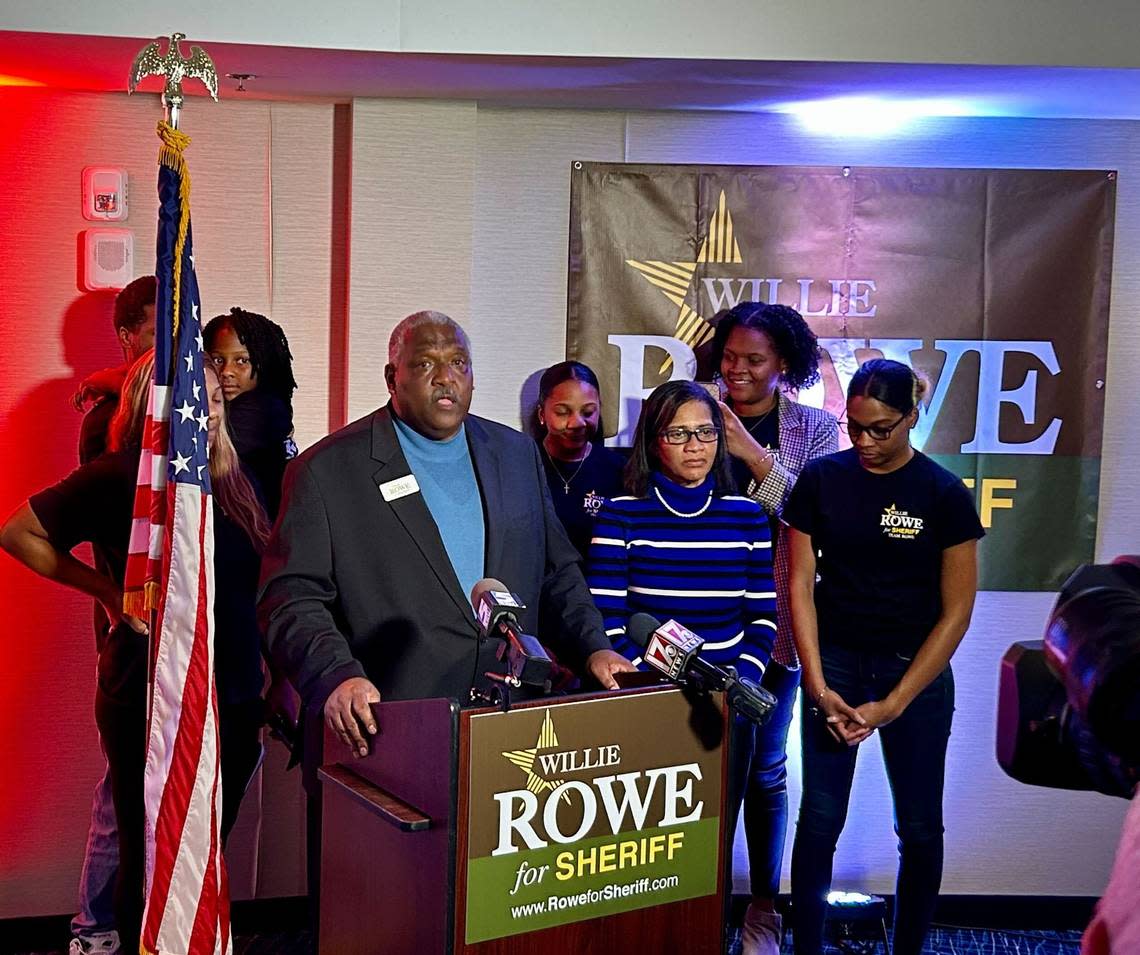

“We knew we couldn’t raise the kind of money that our opponent did ... but we knew we would win it by word of mouth,” Rowe told supporters Tuesday night in a victory speech.

The Wake native also struck a chord with voters in the Democratic core of Raleigh, according to precinct results, in a race that lacked the partisan bickering seen in other races. Harrison, meanwhile, struggled to overcome criticism of his previous immigration policies.

In the end, Rowe said a “grassroots approach” pushed him past the finish line with around 30,000 more votes than Harrison — a closer race than in neighboring Durham County, where the incumbent sheriff easily won with 71.5% of the vote.

Rowe truly had fewer other options than this strategy, as Harrison ultimately raised over $500,000 more than Rowe in the race, according to the most recent campaign finance reports filed in October. Harrison had roughly 12 times more cash available than Rowe did in October.

But before he faced Harrison, Rowe also had to beat incumbent Gerald Baker twice — first in the Democratic primary and then in a runoff. Baker lost both, becoming the first Wake County sheriff in decades not to be re-elected to a second term.

After the votes were counted Tuesday, Rowe could claim victory as one of three sheriff-elects in North Carolina to beat an incumbent in the 2022 elections, according to the North Carolina Sheriff’s Association.

Here’s how he did it.

Support from community

Rowe counted on sheriff’s deputies whose trust he gained during his career, some of whom campaigned on his behalf in the law enforcement community and in Wake County’s towns, he said in an interview.

“When people (in the Sheriff’s Office), from retirees and even current employees, got the word that I was running, you know, they reached out to me because they always remembered the way I treated them,” Rowe told The N&O on Wednesday. “Word of mouth is still the most effective means of communication.”

As an example, he named his professional relationship with former four-term Raleigh Mayor Nancy McFarlane, whom he worked with when he was in the Sheriff’s Office until retiring in 2013.

McFarlane was one of the few people who donated the maximum amount to his campaign.

“I took time to build relationships,” he said.

Three of his previous opponents in the Democratic primaries — as well as Republican sheriff candidate David Blackwelder — also endorsed him.

Harrison told The N&O Tuesday he wasn’t devastated by his loss, and said “a good man” will now run the Sheriff’s Office.

“I just want us to come together and forget about the politics and keep people safe,” Harrison said. “Sometimes we put politics in front of people. We’ve got to learn to work together across the board regardless of where you’re from.”

‘Big and blue’ Wake County

In Wake County, the largest group of voters — 41% — are unaffiliated, followed by 36% registered Democrats and 22% registered Republicans. That statistic put Harrison at a disadvantage from the start.

“Republicans are outnumbered; that’s just the way life is right now,” Harrison said.

A closer look at the map of precinct-by-precinct results in Wake County may also explain Rowe’s victory.

Harrison’s support overwhelmingly came from unincorporated, suburban and rural areas of Wake County, according to the N.C. State Board of Elections precinct map. The precincts won by Harrison are colored red on the map.

But they wrapped around a core of precincts, colored blue, in central Wake, that voted for Rowe. Those hold a majority of the county’s population.

“Wake County is big and blue,” said Charles Hellwig, Harrison’s campaign strategist. “Elections are a math problem, and the math wasn’t on our side.”

Of the roughly 75 people moving to Wake County each day, “they’re probably two to one, Democrat over Republican,” Hellwig said.

Hellwig noted that Harrison received 10 percentage points more votes in his race than Republican Sen.-elect Ted Budd did in Wake County.

For Harrison to win, he had to take the majority of Republican votes, get Wake’s unaffiliated votes and pick up nearly 20% of registered Democrats’ votes, based on numbers gathered from polling, Hellwig said.

Immigration policy controversy

In his 2018 campaign and again this year, Harrison struggled to get past public criticism surrounding his stance on immigration — a consequence of his office’s adoption of the 287(g) program.

Under the program, Wake officers screened the immigration status of people in the county jail, leading to them being turned over to federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents for potential deportation.

Baker successfully campaigned in 2018 on removing the program if elected. Counting on Democratic fervor at the time, he got the support of voters, and the ACLU spent $100,000 in advertisements attacking Harrison.

“Sheriffs are (not) normally seen as being a real political,” said Hellwig. “Part of what happened in 2018 was that he was lumped together with Trump because of 287(g). So it kind of became political.”

This election, Harrison said he would not bring back the program if re-elected because he said the county no longer needed it to verify identities in the jail. But area activists decried the move as too late to sway their opinions about Harrison, The N&O reported previously.

On the other hand, Rowe publicly opposed the program for the better part of a decade, saying it violated due-process rights for people arrested in the county.

“(Harrison’s) defeat, for members of the immigrant community, is a victory,” said La Fuerza, a Raleigh Latino advocacy group, in a statement.

La Fuerza, along with the ACLU of North Carolina, expressed public skepticism of Harrison’s policy reversal previously.

Also working in Rowe’s favor were get-out-the-vote events in the Latino community by El Centro Hispano, a nonpartisan organization that publicly criticized Harrison’s record.

Rowe speculates that his message resonated beyond registered Democrats.

“We were talking about, you know, not any type of favoritism or special treatment, but just ... equality, fairness across the board,” he said. “ And I think young voters today, whether people of color or not, you just want to be treated fair.”