Wonder why some Canton neighborhoods struggle? Attorney points to history of redlining

CANTON − Richard Harper says it isn't a coincidence that certain neighborhoods struggle more than others.

The roots of the disparity, he argues, can be traced back decades, when the federal government enacted a home loan program that inadvertently — or deliberately — created a now-outlawed practice known as "redlining."

Redlining was a process by which mortgage companies rated neighborhoods, and issued or denied loans based on four grades and colors, the worst being red.

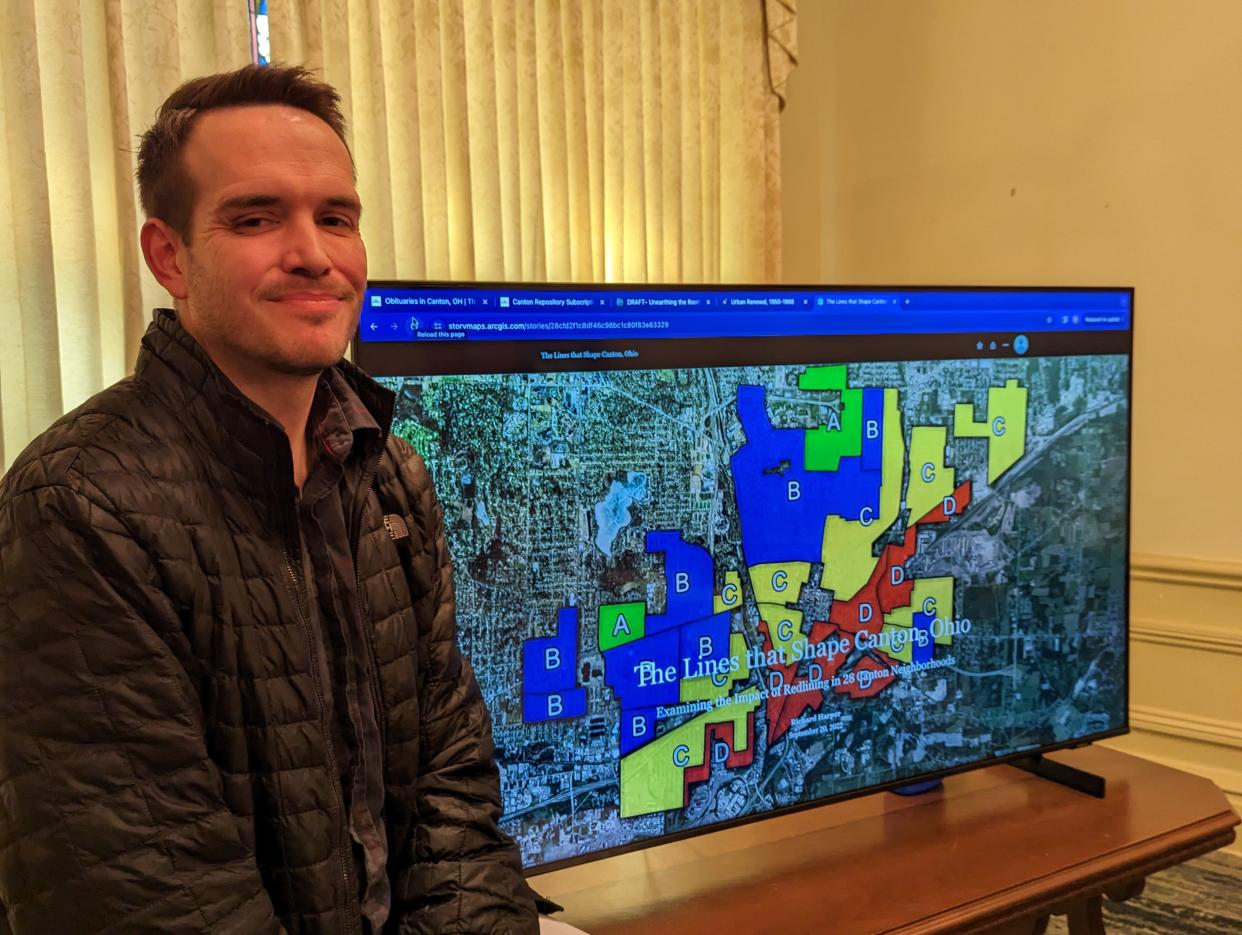

Harper published in 2022 "The Lines that Shape Canton, Ohio: Examining the Impact of Redlining in 28 Neighborhoods," an online and interactive project about how the city's neighborhoods and the people in them have been impacted.

"I grew up playing basketball at the old downtown YMCA, J Babe Stearn, the Southeast Community Center and others and was often one of only a few white kids on my teams, so my first sense of team and community was predominantly Black," he said. "Those early experiences provided me an invaluable perspective and understanding, which continue to shape me and inspire my work, such as projects like this one."

An attorney, Harper said his curiosity about redlining was piqued while working for the Stark County Prosecutor's Office. He now works as a field representative in Stark County for U.S. Rep. Emilia Sykes, D-Akron.

"We were working on a grant in the Stark County Prosecutor's Office and we were looking at low-income census tracks and the crime rates that are generated within those low-income census tracks," he explained. "I was looking at these different census tracks and at the concentration of crime that we were seeing and it was almost perfectly fitting within these different patterns. I remembered that Canton was redlined, but I didn't really know much of the history about it."

How Canton was redlined and what it meant for neighborhoods

He said he learned that Canton was one of more than 200 cities redlined.

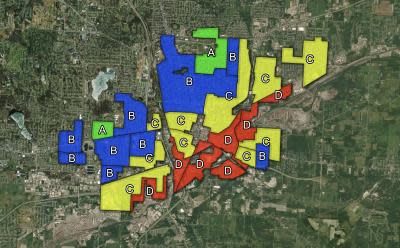

"I was like, 'Well let me let me play around here and see if I can look at a redlining map and compare it to these low-income statistics that I was seeing,' and sure enough, it almost perfectly aligned," he said. "On the east side of the city is where you really see the heaviest and the most concentrated levels of disparity."

The roots of redlining are found in the Home Owners Loan Corp., an agency created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration in 1937 which issued mortgages based on a neighborhood's desirability. According to maps archived at the University of Richmond, the Home Owners Loan Corp. gave two Canton neighborhoods — Ridgewood and Harter Heights — green or "A" ratings.

More on redlining: As online banking grew, mortgage lending regulations didn't follow suit. Until now.

Much of northwest Canton, and Colonial Heights in northeast Canton were given blue or "B" ratings for "desirable." Central and northeast Canton were marked in yellow and given a grade of "C," implying decline.

Southeast Canton was rated with a "D" and swathed in the color red as a means of discouraging banks and mortgage companies. It meant that the existing homeowners there could not secure loans for home improvements, or get a fair price when they tried to sell their houses.

"When we see these areas around Stark County where they were able to have a house and invest in it, and then sell it and get the bigger house, or sell it and finance their kids' college and so on and so forth, those sort of wealth building opportunities weren't available to Black residents," Harper said. "And then especially when you consider the destruction of Cherry Avenue, just imagine having those businesses to pass down."

Black gold: The golden age of Black business in Canton

'We need to understand that systematic injustices can exist, even if we do not see them.'

Harper's research also includes details on the destruction of the Madison-Lathrop neighborhood in southeast Canton, where more than 1,100 residents — 97% were Black — were displaced to make way for U.S. Route 30 and industrial space, and given unfulfilled promises that they would receive adequate compensation.

Some of the residents' stories recently were recorded in interviews conducted by students from Malone University.

Professor Jay. R Case, who led the project, said there are several reasons why learning about redlining matters.

"We need to understand that systematic injustices can exist, even if we do not see them," he said. "Some people think that racism or discrimination is only a matter of individual hatred or individual judgmentalism. It is that, but we need to understand that discrimination can also be built into market systems and government policies in which some people involved may not even be thinking about the impact of the system on other groups of people. Redlining contained all of that."

Case said redlining also matters because home and land ownership has been one of the most common ways Americans have been able to build up equity and generational wealth.

"Redlining not only placed steep obstacles in the way of certain groups in the United States, it slowed down the overall economic prosperity of all of society," he said. "If we want the United States to better, realize its promises of economic opportunity, we need to understand how, where and why obstacles get erected. We also need to understand that nobody climbs up the economic or social ladder on their own hard work alone. Hard work matters, but other factors are at work that determine whether a person faces opportunities or serious obstacles in that process."

Redlining aided by 'racial covenants'

Harper also took a look at "racial covenants," which predated redlining in prohibiting Blacks, Jews, Asians, Greeks and Italians from purchasing homes in certain neighborhoods.

"Racial covenants were pretty wild for me," he said. "I knew that they existed."

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable but they weren't made explicitly illegal until the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

"And so really what the court was doing there is saying that the government could not play a role in enforcing these racial covenants. However, private parties could and they very much did," Harper said.

One of the most infamous examples of a racial covenant community was Levittown, New York, five tract-housing suburbs designed and built specifically for white World War II veterans. Levittowns were built by developer William Levitt in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and in Bowie, Maryland.

Harper noted that although Stark County is 88% white, racial covenants were a factor in residential development as far back as the 1910s, including in Hills & Dales, Avondale, Colonial Heights and Menlough Estates.

"Stark County was very rampant with racial covenants," he said. "As Stark County was growing and expanding, developing these new neighborhoods, a lot of these covenants were put into property deeds. It did evolve over time. In the 1950s, you start to see Jewish folks, Italians and Greeks being able to blend in and assimilate. And then you still see the concentration of minority neighborhoods, which you know today primarily means 'Black.'"

'People scattered everywhere'

Wilhelmina Jackson Glenn was a teenager when her parents, Price and Mary Jackson, were forced to leave the home they owned at 908 Lafayette Ave. SE because of urban renewal.

"I lived in that house since I was born. They were very upset," she recalled. "I know that they attended several meetings. The neighbors were all close and I can remember some of the neighbors get together and were discussing what they were going to do."

Glenn said her older sister, Patricia Jackson Stokes, recalls how their mother resisted efforts by Realtors to steer them and other displaced Black families to buy homes in the 12th Street NE neighborhood.

"My mother said you could see where it was already starting to run down," Glenn said. "That's how we ended up farther out. I know that my parents were real money conscious. My mother was a saver, so I think that made it maybe a little bit affordable for us to move out further."

Glenn said her parents purchased a home farther east on Ellis Avenue NE, noting that her mother lived in the house until her recent death at 90.

"The thing I think that helped my parents was my mother and one of her sisters used to work for Stern & Mann's (department store), and I think that my mom probably had a few connections because of the people she worked for and they were around," she said. "They kind of helped her to navigate through that process of trying to find a home, so I'm thinking that's part of what may have helped them because we ended up moving into an all-white neighborhood."

But Glenn said the move was traumatic for her, recalling that when they first arrived, a bus driver refused to pick her up for school and her parents had to go to the district to complain.

"I had to walk two blocks to the bus stop, and white people were looking like, 'What are you doing out here? Who is this person?' I didn't have anybody to walk with me," she said. "I had two younger brothers who went to grade school off Harmont Avenue. They had each other."

Glenn said their former neighbors had varying success in finding comparable housing.

"(City officials) didn't realize the trauma of moving, of people having to start all over when they were used to living in a such a close-knit environment," she said. "I know that everybody was trying to find a place to live. People scattered everywhere. That's how we kind of lost track of some people."

Is redlining still being practiced?

Malone University history professor Jacalynn "Jacci" Stuckey, who has studied the impact of urban renewal on southeast Canton, contends that redlining is still being practiced.

Recently, state Rep. Josh Williams a Black Republican, called for a new state law against redlining after he said he was denied a home based on his race.

"The reason I say that redlining is still practiced today is because implicit bias, fostered by government programs that sanctioned and perpetuated racism, is very difficult to vanquish from our collective mindset," Stuckey said. "Blacks and other people of color are still more likely to be relegated to areas that were redlined or 'yellow-lined.' Furthermore, zoning laws also serve to perpetuate the ill effects of redlining, since current zoning ordinances often restrict affordable and multi-family housing to the old redlined, yellow-lined, and, in older central cities like Canton, blue-lined areas. And gentrification, which may restore redlined areas, are often beyond the means of poorer folks."

Stuckey noted that in 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court held that segregation in the U.S. is "de facto," meaning, it's based on private decisions, as Harper mentioned.

"As long as the current Supreme Court argues that segregation is due to private decisions and not past and current U.S. policies, racial discrimination in the housing market will continue," she said.

Harper has shared his research with local health departments, Habitat for Humanity and the United Way. He said he has offered to give a presentation for the Canton City Council but hasn't received a response.

"I originally shared this online because I wanted to provide an understanding of people and places our community too often stereotypes," he said. "By providing historical context, I hoped my following would begin to understand how past practices of redlining and urban renewal continue to affect the overall health and equity of our communities. I also wanted to generate awareness, which can lead to advocacy for more equitable policies and practices. Some folks might have known about redlining and urban renewal, but few truly understand the impact locally."

Late last year, the city landed a $500,000 economic development planning grant through a new federal program and is a finalist to receive up to $20 million to invest in the city's southeast neighborhoods. Canton is the only Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program (Recompete) finalist in Ohio.

"You know, the data is really compelling but when you can connect with the community narrative and the history that's there, that's really the most compelling part for me," Harper said.

Reach Charita at 330-580-8313 or charita.goshay@cantonrep.com

On Twitter: @cgoshayREP

More details

To view "The Lines That Shaped Canton" project, visit: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/28cfd2f1c8df46c98bc1c80f83e83329.

For more information, contact Harper by email at: rah138@georgetown.edu

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Richard Harper publishes online analysis of redlining in Canton