My Wife's Chronic Illness Has Put Me in a Role I Never Imagined: Caregiver

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

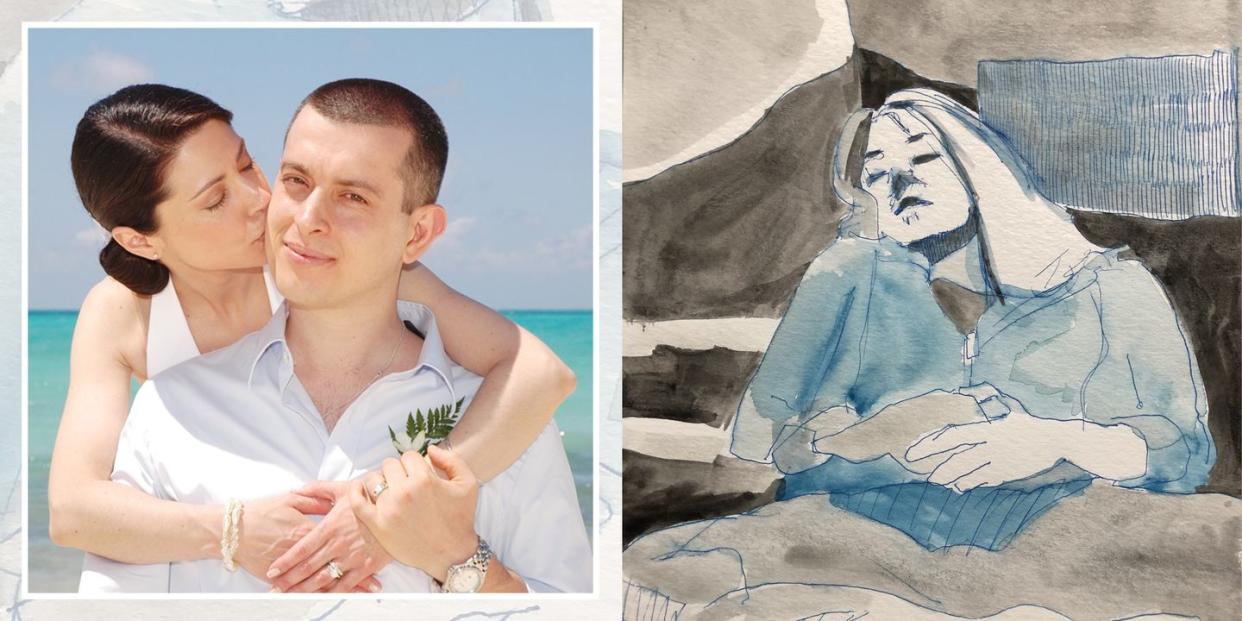

When my now-wife Emily and I met two decades ago, I knew this much: I wanted to be in love. After surviving the clumsiness and yearnings of dating life, I craved security and deep connection, and Emily seemed like a good bet. On the surface we were opposites — I’m an arts and culture nerd; she’s a science and nature nerd — but you know that great feeling when you can be yourself around someone? We had that and more, which proved essential in dealing with the challenges that lay ahead, especially an uninvited guest: Emily’s chronic illness.

When Emily was 22, she developed Crohn’s, an autoimmune disease that attacks the digestive system. It came on swiftly and without warning. She was later diagnosed with chronic migraines as well as convergence insufficiency, a neurological spatial management disorder which makes tasks like tracking anything — words on a page, images on a screen, looking through a windshield — debilitating. As the daughter of a gentleman farmer, Em grew up mucking stalls, chopping wood and cleaning the chicken coup. A two-sport athlete in high school, she was always on-the-go. All that came to an end when she got sick; by the time she turned 30, Em had undergone nine surgeries related to Crohn’s, including one that removed her colon and fitted her with an ileostomy bag.

As we got to know each other, Emily took great pains to introduce me to her reality slowly — she didn’t want to scare me away. Plus, she didn’t want to be known as “the sick girl,” didn’t want people to feel uncomfortable or burdened. What would they say, anyway? This is how she lived with chronic illness.

The funny thing is you would never know she was ill by looking at her because, as I soon discovered, she spent most of her energy carrying herself as if she was completely healthy. She rarely left the house without make-up, always dressed nicely and greeted people with a firm handshake, direct eye-contact and a smile. She worked as a unit secretary in a hospital ER and exuded poise and courteous professionalism.

As for me, the world of doctors, hospitals and operations proved intimidating. I was fuzzy on the most basic medical terms, didn’t know a comorbidity from a colonoscopy and had never heard of, let alone seen, an ostomy bag. I banked instead on a willingness to show up. My father stopped drinking when I was 12, and early in his sobriety he took my sister, brother and me to A.A. meetings with him and didn’t care who thought it was inappropriate. Being thrust into adult reality beyond our experience helped condition me for the unknown. So while the prospect of contending with Emily’s illness scared me — because I didn’t know what that looked like or what would be required of me — that didn’t stop me from jumping into the deep end of the pool. All I had to do was learn how to swim.

Adjusting to Our New Reality

It wasn’t long before I discovered the all-encompassing nature of Emily’s illness. Her condition dictated how much energy she had, where she could go and for how long and what she could eat. It impacted both of us in ways I didn’t anticipate.

I come from an epicurean family — food is joy and pleasure. When I was growing up, my Belgian-born mother greeted the day with a cup of coffee, spreading Marmite or homemade jam on a burnt piece of toast at breakfast, as she joyously schemed what to make for dinner.

For Emily, food, first and foremost, is sustenance and health. Flavor and enjoyment are secondary concerns at best. So as much as I loved cooking, I had to learn to approach it in a different way. I began using all sorts of ingredients that were new to me — flax seeds, quinoa, kale. Since Em can’t digest raw vegetables, I puree vegetables into soup; something as simple as onion, walnuts, broccoli and soy milk will do the trick. It may not be fancy cooking but the chef’s satisfaction remains — making something simple and good for an appreciative eater. And she is never less than appreciative.

Choosing a restaurant also became an ordeal. We carefully inspected menus online, crossing contenders off the list, both of us losing our patience. I wasn’t always easygoing about our food challenges. I took it personally when Em couldn’t digest an ingredient I wanted to use and I let my disappointment about our dwindling restaurant list get in the way of adjusting on the fly and staying upbeat. Emily, in turn, felt crappy about upsetting me but was also pissed at the situation: it wasn’t as if she could control what she could eat. Being thought of as the problem tapped into why she didn’t even like to consider herself as sick; sickness meant weakness and dragged down everyone around you.

Intellectually, I understood it was a matter of plumbing not taste — and even if it was about taste, it still wouldn’t have been personal. Getting beyond that took time. I became accustomed to hanging out with friends or attending family gatherings alone — sometimes because Em was working or resting to go to work, and sometimes because she wasn’t feeling well. She always encouraged me to go out, soak up my friends, nourish myself and then come home and share what I’d seen and heard. If I missed her being with me, I also enjoyed being free to come and go as I pleased.

Some letdowns were more disappointing than others. When Em wasn’t available to be romantic or sexual, that was tough and I’d fall apart. I didn’t yell or scream. I sulked and brooded. Then, to mask the anger, I cleaned the apartment and went out of my way to be helpful and extra good, as if being good had anything to do with it. I felt sorry for myself, as if self-pity would help (pro tip: nothing is less sexy than self-pity). Frustrated, I ate too much, smoked too much weed and stopped exercising (pro tip #2: smoking weed, gaining weight and not working out is almost as attractive as self-pity).

The bombshell disappointment involved children. I always assumed I’d be a father, but motherhood was not a realistic option for Emily. She struggled to take care of herself, how would she have the energy to be a mother? For years, I would not accept this; we went to couples therapy and put off getting married. A lot is negotiable, so much of life is gray, but this was a legit deal-breaker. After all, you can’t have half-a-kid. By the time we married I still privately hoped that parenthood was a possibility. If not, wouldn’t I regret it the rest of my life?

My New Role: Caregiver Husband

Before long, I replaced Emily’s parents as her primary support. Sitting in doctors' waiting rooms together, we played Pictionary on scraps of paper; she beamed with pride at her indecipherable drawings, unable to suppress a laugh. On a few occasions, I caught a look of genuine surprise on the nurse’s face as they regarded the thickness of Emily’s medical chart. I often sat in the examination room, poised with notebook, pen and good posture. Even if I didn’t understand a lot of what they were talking about, I could pretend like I did and, in the meantime, take diligent, smart notes, which could be of use to Emily after the appointment.

At first, I talked too much to the nurses and the doctors, small talk, a habit that makes me feel less anxious in those situations but that was not at all helpful to Emily. I quickly understood the less I said the better. Occasionally, I would remind Emily of a question she wanted to ask, otherwise I kept quiet and took notes. The days and weeks leading up to an appointment were tense with anticipation and expectations. It became clear to me that each visit — to a western doctor or a holistic practitioner — came loaded not only with trauma history but an almost desperate hope for answers nobody seemed to have. When the appointments inevitably did not yield desired results, the aftermath of defeat lingered for days, weeks.

The most unsettling adjustment came when Em didn’t feel well. After eating, she’s careful not to move around too much while digesting because the scar tissue can lead to an “obstruction” — picture your intestine bent like a kink in a hose. She’s endured hundreds of partial obstructions. The bad ones put her on the bathroom floor curled up in pain, unable to speak. A couple of times we drove to the ER in the middle of the night. One came on New Year’s Eve. I paced outside an exam room as two nurses fumbled to insert a nasogastric tube up her nose — the tube is threaded through the nostril down the throat and into the stomach — and listened to her gag. I stopped pacing, as if my stillness would help them steady their hands. The nurses took breaks, I held my breath and Em kept choking until they threaded the tube properly.

It is a particular kind of challenge watching a loved one suffer. There are moments when the pose of “I’m not sick” falls away and Emily is infuriated by her reality. She teems with anger. Sometimes she’s overwhelmed with sadness. And when she’s in either state — fury or sorrow — it’s difficult to resist the urge to swoop in and try to fix things. As if there was anything that could be fixed — other than my anxiety in experiencing my wife’s anger and sadness.

Since we’ve known each other, Emily has doggedly pursued knowledge and wisdom when it comes to feeling better in her own skin. She’s a Wellness OG, reading pioneers such as Louise Hay and Wayne Dyer back in the mid-’90s. Em’s incorporated tapping, guided meditation, reiki, crystal healing, earthing and humming — yes, humming one continuous note, ooooohhhmmm — to her self-care repertoire.

I’m a skeptic by nature but my attitude is “whatever works” and not only that — I’ve picked up pieces of wisdom here and there and found them useful, such as the sense of surrender and acceptance Anita Moorjani describes so eloquently after a near death experience in her 2012 book, Dying to Be Me. A copy of Eckhart Tolle’s A New Earth now rests on my night table.

Emily lives a rich inner life. She’s an introvert and enjoys her own company in a way I envy. When she’s down, however, Emily shuts the world out. She’s gradually warmed to the idea that she can reach out to one of her trusted friends when she feels like shit; she can let them see the “unwell” her. One of my favorite sounds in the world is hearing her talk and laugh on the phone with a friend. I’m relieved that she’s comfortable enough to confide in someone else other than me, especially a someone who can provide nutrients and understanding beyond my reach.

The Highs and Lows of Being a Caregiver

Though Emily remains self-sufficient in most ways, she often leans on me for emotional support. When the pain and frustration of not feeling well becomes too much, darkness replaces Emily’s usual optimism. Unsure what to do with her anger she points it inward, blaming herself for being sick as if it were due to a lack of character. Sometimes it gets so bad she excuses herself from the room.

These spells can last hours, days. In the past, my approach was to do something, anything to help her feel better. Whether I had the energy or attention or not, I’d listen, cajole, cheerlead. I wanted so badly to take away her pain that I drained myself. When my wife got upset, I dropped everything, no questions asked. Em encouraged me not to exhaust myself even though it was my choice to get involved. Normally, once Emily’s mood lifted and the storm passed, she’d be present and loving. I didn’t feel grateful, but bitter. Where’s mine? What about me?

I found a huge measure of relief in therapy. Having time set aside for talk therapy was crucial for the validation alone. I also attended a weekly men’s group run by the same therapist. Taken together, I had a place to share and connect and feel less alone. The group, usually a half-dozen men, ranging in age from their 20s to their 70s, listened to my dilemma and my stories. They also challenged me. It's easy to blame things not going my way on Emily and her illness, but what was my part in creating my own suffering? The focus always came back to that.

Here is a woman that loves you, they reminded me. She champions you, says you’re hot stuff, lets you be yourself and doesn’t want to control you. She’s independent, and so while you do most of the shopping and all the cooking, she holds her own and then some keeping the family finances, handling the laundry, scrubbing the bathroom. She just can’t be available for you all the time the way you would like. That doesn’t give you an excuse

to go to pieces or stop taking care of yourself. You chose to get involved with someone that deals with a lot, what did you expect?

At the same time, they pointed out how critical I was of myself, that I refused to cut myself a break. How do you face taking care of yourself when you’ve always pushed the responsibility off on others? My concept of love was transactional. I gave and expected a lot in return. The group encouraged me to find love in the giving. What if I could let go of controlling and evaluating what comes back, trusting, since I had an empathetic and supportive partner, that it will come back. Nobody can make you happy or make you whole or any of that shit, they told me, week in, week out, year after year. That’s your work.

“You can have anything you want,” the therapist liked to say, “you just can’t have everything you want.”

Our Messy, Wonderful Life, 20 Years Later

A few months ago, Em and I celebrated the twentieth anniversary of our first date. Our life isn’t tidy — but since when is an authentically-lived life, tidy?

We still get in arguments despite being more conscious. Emily’s health is still unpredictable in ways that are challenging and sometimes scary. Yet her resolve is deep and abiding. She left her job in the ER after 21 years at the start of the pandemic, and now works as a Life Coach and Reiki Master specializing in relief from anxiety.

Like many women, she stopped dying her hair during the pandemic and is now a silver-haired Goddess, more radiant than ever. Proud, accomplished and, incrementally, softening within herself, my admiration for her is undiminished. Our lives don’t look anything like I imagined. But a funny thing happened six, seven years into our marriage, after all our friends and siblings had children and those kids got a little older,

I realized, wow, it’s ... okay not being a dad. I hadn’t expected that. I figured I’d regret not being a father. But instead of seeing a void in my life I saw space, and I filled that space with nurturing relationships, a productive, satisfying creative life and an intimate connection with my wife. In other words, just what I’d always wanted.

Hear More of Alex and Emily's Story

For years, I encouraged Emily to share her chronic illness experience and for years she said, “Until I get well, there’s no victory.” No story to tell. And I said, “That’s not the point. The story is how you handle yourself in the face of illness and all that comes with it.” In 2018, Emily agreed to let me write about us in an essay for Men’s Health. It was a nervy, courageous thing for someone as private as Emily, but she felt if her story could help a potential reader feel less alone in the world, it was worth doing.

When Audible approached me about doing an original audiobook about living with someone that has chronic illness, I knew including Emily’s voice would make the project so much stronger. She’s not a performer — and is not a ham — but she has the rare ability to sound natural when someone sticks a microphone in her face. So we made a 30-minute demo at home, just the two of us, and when the folks at Audible heard it, they said, “We want both of you.” Last summer, Emily and I recorded a two-and-a-half hour Audible Original remotely from our home. You’ll hear both of us on Here I Are: Anatomy of a Marriage, our she-said/he-said account of how we deal with chronic illness and other potential relationship dealbreakers such as money, sex, kids, you know — life!

You Might Also Like