Why Do Viruses Exist, Anyway?

I’ve had it up to here with viruses lately. It’s easy in these times to wonder whether there’s anything good about them. That made me curious about why viruses exist in the first place, and where they come from. So, let’s take a few minutes to talk about them. Not about the infamous SARS-CoV-2 virus that’s been in our lives for over two years now, but about viruses as agents that exist against the larger backdrop of life on this planet.

Though they are puzzling and frustrating at times, viruses are really quite impressive, according to researchers whose lives revolve around studying them. A small group of genes in an ingenious casing that can rapidly evolve to continue defeating cellular defenses, a virus is like an ever-adapting robot, designed to do just one thing—keep making copies of itself. Unlike all other forms of life in our world, a virus doesn’t create its own energy to keep going; it’s not made of cells, and it doesn’t grow. It uses nothing in the environment, except the cells of other living things, which become hosts to each replicant virus.

🦠 Science explains the world around us. We’ll help you make sense of it all. Join Pop Mech Pro.

We’ve probably identified only a small percentage of the viruses that exist in the world—and where they came from, nobody knows. “Several theories have been proposed as to whether viruses came before or after cells,” Alan Rothman, a viral immunologist at the University of Rhode Island, tells Popular Mechanics. Rothman has been researching immunity and the pathogenesis of viral diseases in humans (that is, the way a disease develops) for more than 30 years. It’s a chicken-and-egg question. While viruses do have a structure holding them together, Rothman thinks the genetic component that drives their behavior probably came first. Why? “The structural part wouldn’t have made sense in the absence of cells,” he says.

People have long wondered: are viruses alive? But according to Rothman, asking whether viruses are an actual form of life is not a relevant question. “I find that more of an amusing question and more of a kind of thought exercise,” he tells me. The reason it’s not a practical question is that people are still trying to understand what life itself is, he explains. “So I would say, the majority of people would probably come down on the side of saying that you can’t call viruses living or alive at least, but they are part of life. They teach us a lot about life.”

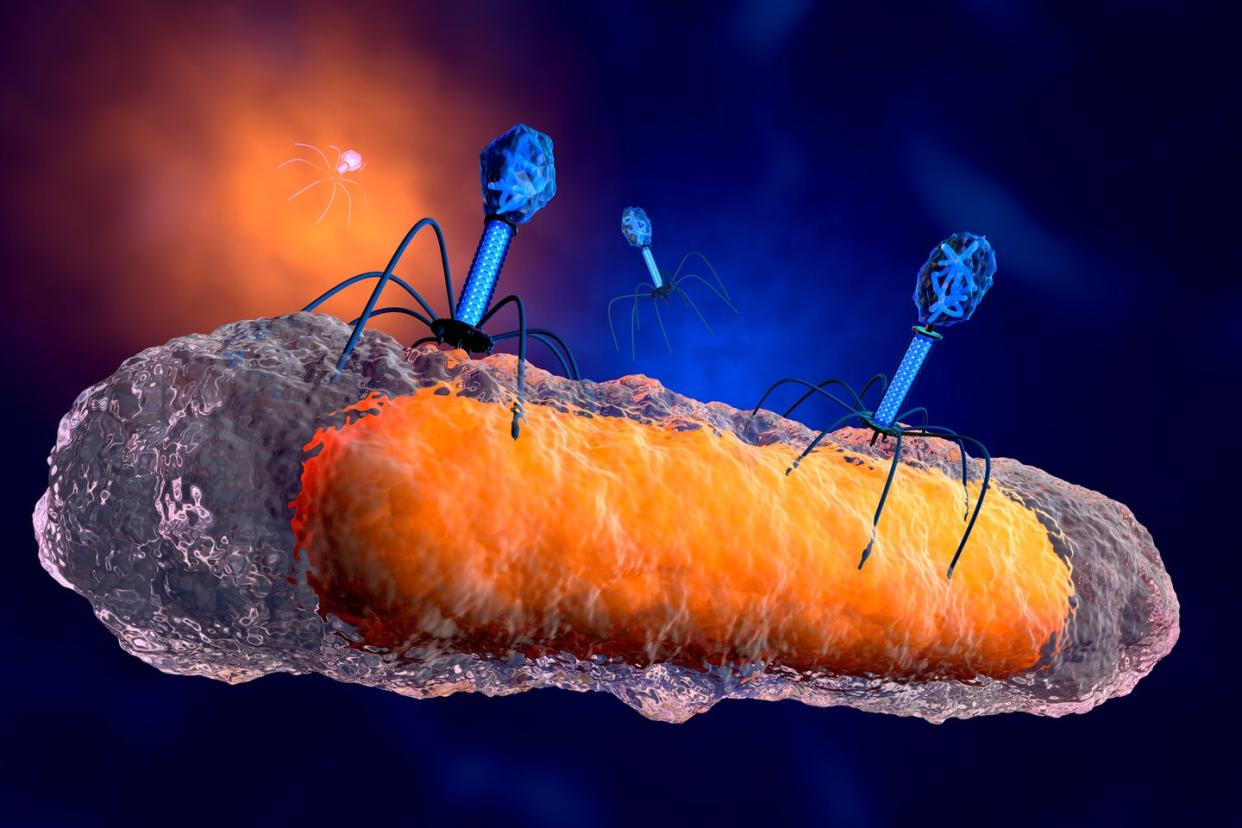

These infectious agents are everywhere. We play host to a number of viruses. Many of them are totally harmless to us. In fact, our bodies’ bacteria have their own viruses, called bacteriophages. “Every branch of life has a virus associated with it,” Rothman explains. And then there are viruses that can even infect other viruses. At least one such case has been discovered, he says.

Viruses really pack a lot of information into their short genome. “It’s kind of like a Swiss Army knife, especially the small viruses,” Rothman says. “They have to use their proteins to do everything. So they’ll have one protein that will have at least five different functions, and we’re still discovering new functions for them. You know, it’s one of the more fun parts of virology to see.”

For example, the dengue virus, which is spread by mosquitoes and causes high fever, rash, and muscle and joint pain, makes ten different proteins that do everything. (By contrast, we humans have tens of thousands of proteins, each with a unique function.) Three dengue proteins create the virus particle itself, and the other seven proteins are responsible for all the other viral functions, such as changing the structure of the cell they infect, copying the viral RNA, and shutting off all of the host cell’s abilities to fight back. So every protein must have two or three different functions. “They’ll put enzyme functions that have no business being part of one another together. It’s just an incredible machine,” Rothman says.

This elegant multi-functionality is cool, but here’s a fact about viruses that’s really breathtaking: despite the baneful qualities of some viruses, like causing disease and death, we can thank these seemingly simple bits of genes for shaping life as we know it. Viruses really drive home the point of evolution—that every species, and viruses themselves, are constantly in a state of change, responding to other living and nonliving things in their environment. Some of our evolutionary traits spring from retroviruses, which are a type of virus whose genes become entangled with our own DNA and are passed on to future generations.

“If you look at the human genome, there’s a reasonable percentage that is actually incorporated retroviruses,” Rebecca Dutch of the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, where she studies human respiratory viruses like COVID-19, tells Popular Mechanics. While our bodies don’t necessarily use many of these inherited viral sequences, some genes have fundamentally changed our species over millennia.

About 160 million years ago, the small furry ancestor of all of today’s mammals laid eggs. A symbiotic retrovirus altered its reproductive traits over many generations, until mammals evolved the ability to grow offspring inside their own bodies. Previously, an animal had no ability to keep its own blood supply separate from a new organism maturing inside it. But a viral gene, and probably genes from several different retroviruses, were instrumental in the development of the placenta, the organ the mother grows to keep her body separate from a new fetus. This gene probably originates from a retrovirus for the proteins that cause fusion between the virus and the cell, says Dutch. “Instead of fusing the virus to the cell, it’s fusing the cells of the placenta together,” she explains.

This change sparked an evolution that allowed the proto-mammal’s body to keep itself separate from the fetus, even as it removed waste and provided oxygen and everything the developing fetus needs. “Essentially in this case here, we hijacked something a virus had, for our own benefit,” Dutch says. It’s now part of our own genetic makeup, packaged in a gene that’s involved in sperm-egg fusion. “So there are cases like that. What’s come out of viruses turns out to be a key part of us. It’s amazing,” Dutch says. So maybe we don’t have to worry about the ubiquity of viruses.

Viruses can, and do, turn our world upside down. But they also made us into what we are. While viruses hold enough mysteries to keep researchers busy for many lifetimes, the scientists are sure of one thing: these odd companions will likely always be a part of life.

You Might Also Like