Why is the man Macon was named for buried beneath a pile of rocks?

The pile of rocks atop Nathaniel Macon’s final resting place lends new meaning to gravestone.

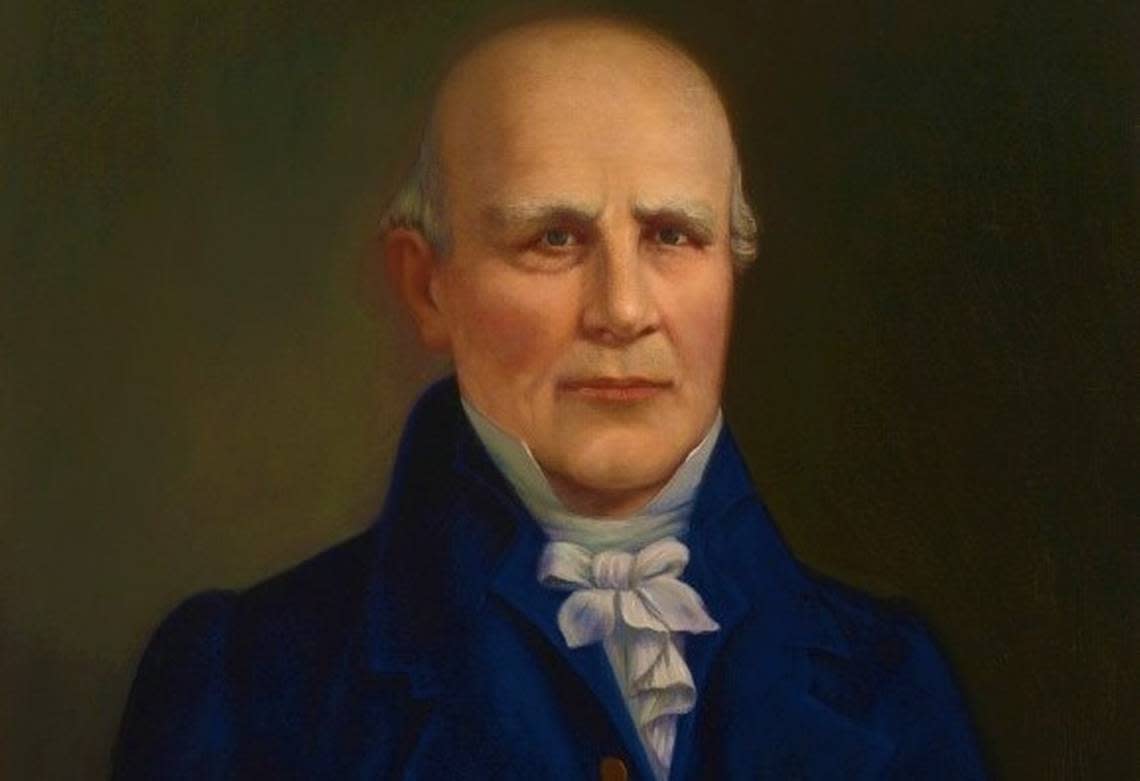

Macon, for whom the city of Macon, Georgia, is named, was a renowned statesman from North Carolina. He fought in the American Revolution, served as a U.S. representative and House speaker, and was a two-term U.S. senator.

His grave lies 4 miles due south of the Virginia border at Buck Spring Plantation near where he had lived, about 50 miles northeast of Raleigh.

What is curious about his burial site is that it was — at his behest upon his death in 1837 at age 78 — covered with stone.

The majestically unkempt tomb was erected, or perhaps deposited, at the edge of his family farmland, again per his instruction, in an out-of-the-way, unplantable plot.

The spot sits half a dozen or so miles from, yes, Macon, North Carolina — population 69.

His biography, “The Life of Nathaniel Macon,” published three years after he died, noted that it had been Macon’s wish to be buried alongside his wife and a son, who predeceased him, in “a spot of land ... least likely ever to be cultivated.”

The biography further noted Macon’s desire that “after his interment in the usual way ... that a parcel of rock should be brought from a certain one of his fields, and piled upon the grave in such a manner as to prevent the molestation of cattle or other intruders. All of which instructions were strictly attended to.”

Macon had been a childhood neighbor and schoolmate of Benjamin Hawkins, for whom the venerable Fort Hawkins, which now overlooks Emery Highway in east Macon, was named. He had also been a second cousin to first lady Martha Washington. His funeral was said to have attracted 1,200-plus mourners.

The crowd of rocks now assembled on the earth above his coffin, many of them flint, as requested by Macon, no doubt surpasses that number. His grave marker, all but dwarfed by the sepulchral stone, bears a quote about Macon from Thomas Jefferson, declaring Macon “the strictest of our models of genuine Republicans ... upon whose tomb will be written, ‘Ultimus Romanorum,’” or “last of the Romans.”

A 1902 write-up in The Telegraph about Macon, the man, cited another biography of him that described Macon as “plain-spoken, unassuming, approachable.”

The article mentioned how Macon had resigned from the Senate at age 70 “because he said he had sense enough to know he ought to.” He was, it would seem, the kind of fellow who might make arrangements to ensure that his name, long after his death, would not merely be etched in stone, but rather unceremoniously enshrined beneath a heaping mound of it.