Why a healthcare giant has slowed care at a Miami hospital, and where it leaves patients

Dr. Christ-Ann Magloire came to South Florida more than 20 years ago to deliver babies. Her mission was to make it easier for women in underserved areas to get care.

The Haitian-American OB-GYN has helped hundreds of mothers give birth, many at North Shore Medical Center, a North Miami-Dade hospital that for decades has provided medical care to the surrounding communities of Little Haiti, North Miami, Miami Shores and El Portal.

But North Shore is bleeding.

Patients who can’t pay much out of pocket and stingy insurers have made it difficult for the hospital to keep up with expenses, executives say. To the west of North Shore, its sister hospital Palmetto General has also had money problems, with patient care sometimes delayed due to lack of supplies.

And now, both hospitals are up for sale.

Owner Steward Health Care System, considered to be the largest physician-owned healthcare network in the U.S, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy May 6 in hopes of squeezing itself out of debt. Now, the company has put all 31 of its U.S. hospitals up for sale, including five in South Florida, court filings show.

Steward’s CEO, Dr. Ralph de la Torre, who used to live in Florida, said the company’s hospitals and medical centers will remain open during the bankruptcy process. In January 2024, the company began a “comprehensive marketing process” to search for possible hospital buyers. By April, its Florida hospitals were also up for sale, documents show.

And concerns are growing in South Florida over the future of North Shore and its sister hospitals in Hialeah, Coral Gables and Lauderdale Lakes.

North Shore’s maternity ward is already barren. The hospital, just off I-95 at 1100 NW 95th St, unexpectedly closed its critical but costly labor and delivery, neonatal, and behavioral health units in February to try to slow the financial bleeding.

“It definitely felt like a slap in the face,” said Jamarah Amani, executive director of Southern Birth Justice Network, a nonprofit that is working to make midwife and doula care more accessible in South Florida. North Shore was the go-to hospital for midwives in the area to send patients if their pregnancies became too risky, according to the licensed midwife.

A few days after Steward declared bankruptcy, executives had in-person meetings with workers in South Florida. Daniel Knell, president of Steward’s Florida market, told North Shore employees he hoped the bankruptcy process would let them catch up with delayed payments to vendors so the hospital could get the equipment and supplies it needs to be fully operational.

Steward’s CEO, de la Torre, made similar remarks during an in-person meeting with staff at Palmetto General Hospital, 2001 W 68th St. in Hialeah, according to people who attended the meetings.

READ MORE: Owner of five hospitals in South Florida files for bankruptcy. Will it affect you?

Knell also agreed Steward would participate in a June community town hall to discuss concerns residents may have about the future of North Shore hospital, according to DeQuasia Canales, vice president of 1199SEIU, United Healthcare Workers East. The union represents more than 450,000 healthcare workers in the country, including some at North Shore Medical Center, Palmetto General Hospital and Florida Medical Center, a Broward hospital also operated by Steward.

For Canales, her biggest worry is the future of ghostly North Shore. It’s ground zero in South Florida — an example of Steward’s financial crisis.

Palmetto is a “hospital that looks and operates more like a hospital, just with hiccups, compared to when we enter North Shore and it is a quiet place that feels less like a bustling hospital and more like a clinic in terms of the scarcity of the amount of people in there and the quietness of it,” Canales said.

Maternal care deserts increase risk for women, babies

North Shore, which has been a lifeline for surrounding communities for more than 70 years, has seen trouble brewing for months. North Shore employees and union representatives who spoke to the Miami Herald said there have been delays in payments to some workers and vendors, also a problem at other Steward hospitals. Because of overdue bills, vendors don’t want to send the hospital new supplies, and there are delays in fixing broken equipment.

Some workers have had their hours reduced. And some patients had their elective surgeries canceled and are sent elsewhere for care.

But the largest sign things were amiss: the sudden shutdown of the labor and delivery services unit.

North Shore President Alejandro Contreras told employees in a letter, obtained by the Miami Herald, that the February closing of the units happened because the hospital wasn’t making enough money from patients and insurers. But that cost-saving measure has led to a “maternal care desert” in the area, increasing the risk of complications for moms and babies, according to health experts and health advocates.

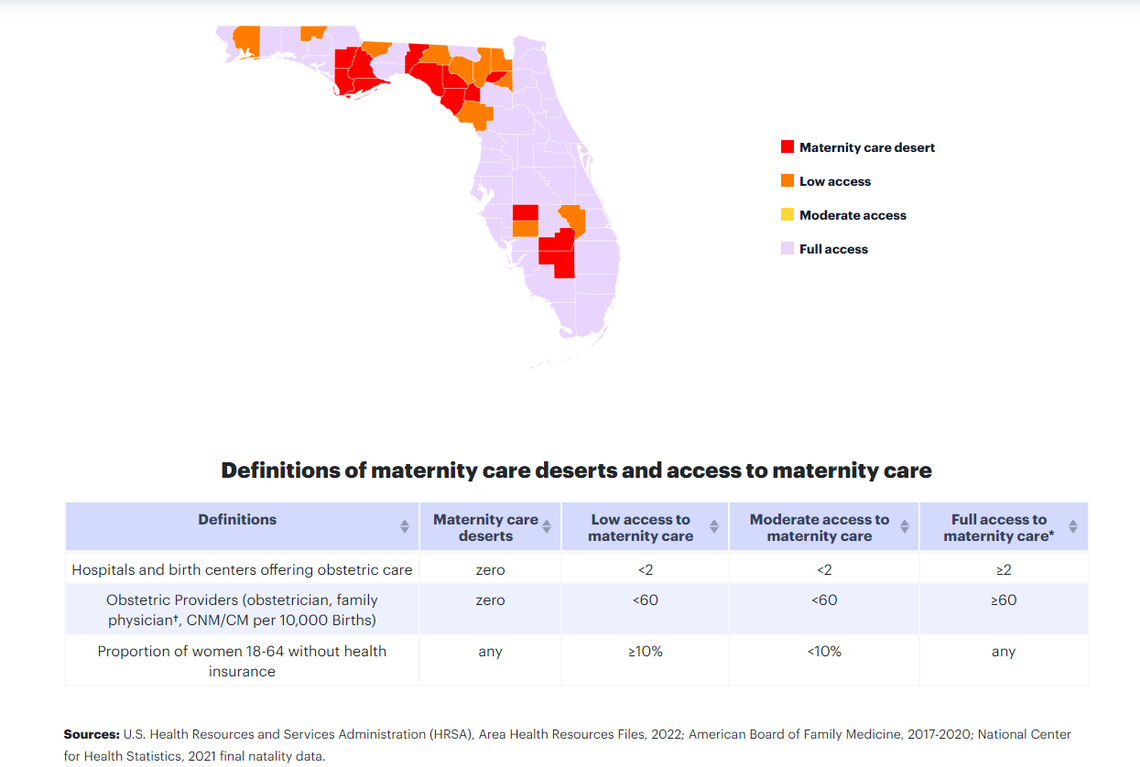

Maternal care deserts are areas where there is no nearby access to birthing facilities or maternity care providers, requiring women to travel at least 30 minutes to get maternity care services, according to March of Dimes, a nonprofit that focuses on the health of babies and mothers and monitors the ease of access to maternal care services in the country.

More than two million women of childbearing age live in maternity care deserts and more than 10% of babies are born each year in these areas, according to Tenesha Avent, the nonprofit’s director of collective impact and maternal and child health for South Florida. About 19% of Florida counties are considered to be maternity care deserts, according to the nonprofit’s 2023 report.

While Miami-Dade County is not considered a desert, North Shore is “just proving that even in Miami-Dade County, which is considered a very metropolitan area, we also are experiencing these challenges when you talk about access to care,” Avent said.

Parts of Miami-Dade County are federally listed as areas that have a primary care provider shortage. It’s what brought Magloire to South Florida, and made her the first woman board-certified Haitian American doctor in the North Miami area.

“That’s why I came here. I came specifically to North Shore” because it was an underserved area with a physician shortage, said Magloire, who for more than 20 years has cared for patients in the community and is the only obstetrician member of the fetal and infant mortality review board for Miami-Dade County.

Its “ironic,” she noted, that instead of increasing access to care, Steward has made the community more underserved then it already was by “eliminating more physicians and unfortunately people of color” with the service cuts at North Shore.

“When patients get taken care of by people of their own cultural background, they do better, they have better outcomes. That’s a fact,” said Magloire, who has her own practice and had privileges at the hospital. This means she was not a direct employee of North Shore but had authorization to practice and admit patients to the hospital.

Patients who would have typically gone to North Shore for maternity care now have to go elsewhere. The nearest hospitals are Jackson North Medical Center and the Women’s Hospital at Jackson Memorial in Miami, both about six miles away and operated by Miami-Dade’s public safety net hospital system. Slightly farther is Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach. Aventura Hospital does not have a labor and delivery unit.

Amani, the midwife who leads the Southern Birth Justice Network, says there’s been a rise in inquiries about home births and birthing centers since North Shore stopped offering maternity services on Feb. 14, weeks earlier then planned. The nonprofit wants to open a birthing center in the area to help fill the void left by North Shore, the midwife said. It’s shopping for real estate, but finding an affordable location will be challenging in South Florida’s pricey market.

“We are a small drop in the bucket ... but we are trying to do what we can with what we have because there really isn’t a choice. We have to save ourselves. No one’s coming for us,” Amani said.

North Shore is the most recent hospital in South Florida to stop offering maternity services. One of North Shore’s sister hospitals, Hialeah Hospital, closed its maternity ward in 2021, and Jackson West in Doral closed its maternity ward in June 2023, mirroring a trend that is happening across the country, mostly affecting underserved predominantly Black and Hispanic communities, populations that have a higher rate of dying from pregnancy-related complications.

“This is going to have a detrimental impact on woman’s care,” Magloire said while discussing the shutdowns of labor units, provider shortages and abortion restrictions occurring in Florida and other parts of the country during an April panel hosted by the Southern Birth Justice Network at the Little Haiti Cultural Center, near North Shore.

The panel, which followed the screening of Paramount+ “The Changemakers” episode spotlighting the nonprofit’s midwifery work, was part of a series of events the birth justice nonprofit hosted for Black Maternal Health Week.

The U.S. has an alarming maternal mortality rate for a developed country — 32.9 deaths per 100,000 births, according to the most recent report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the country’s public health agency. A recently published study in the peer-reviewed American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology suggests the rate is much lower, 10.4 deaths per 100,000 birth.

However, no matter which data you look at, one thing remains true: Black pregnant patients are three times more likely to die than white patients, NPR reports.

Why did North Shore close its maternity ward?

North Shore abruptly closed its obstetrics care unit on Feb. 14. The behavioral health and neonatal units were shut down days earlier. North Shore President Alejandro Contreras told employees in a letter obtained by the Miami Herald that the shutdowns were because the hospital wasn’t making enough money.

“Our maternity unit is overwhelmed with non-paying patients and those whose Medicaid coverage pays us far less than cost. The Behavioral Health Unit is similarly flooded with patients whose insurance plans reimburse us at completely inadequate levels,” Contreras wrote in the letter. “We cannot continue to provide services for which we are not paid or for which we are chronically underpaid.”

Cathy Pague, a Steward spokesperson, told the Herald in an email that the decision to close the units in February, instead of March as initially announced, were due to various factors including “staffing level challenges and adjustments to our overall business plans.” Pague said “the impacted employees were offered the opportunity to apply for open positions at North Shore or any other Steward hospital.”

Some doctors, like Magloire, are still trying to get credentials to work at another hospital. The reductions in North Shore’s services already had hospitals doctors, nurses, health advocates and patients worried the hospital would close entirely, similar to what’s happened at other healthcare facilities owned by for-profit Steward Health Care System.

READ NEXT: Midwives on wheels? Pregnancy clinic goes mobile to bring services to Miami neighborhood

Steward’s bankruptcy announcement raises the stakes — not just at North Shore, but at Palmetto and other hospitals across Steward’s network. At Palmetto General, workers sometimes have to send patients to other hospitals because they don’t have the necessary equipment and supplies, although it’s not as bad as at North Shore, according to Canales, the 1199SEIU union vice president, and Lazaro Garcia, a registered nurse who works in Palmetto’s ICU unit.

Garcia, who has worked at Palmetto for nine years, said the hospital has seen a variety of supply shortages under Steward’s ownership, including towels and linens, needles, catheters and medication.

“We started getting short on everything,” said Garcia, who also serves as Palmetto’s chief representative for National Nurses United, the union that represents more than 224,000 registered nurses in the country.

Palmetto is understaffed. Doctors complain about paycheck delays. And patients are worried their care will be affected now that Steward is in bankruptcy, according to Garcia.

“We’re telling patients that as long as we’re here and the doctors are here, we’re not gonna leave,” Garcia said. “We’re going to be here with you until the doors close.”

Steward Health Care’s money problems

Before filing for bankruptcy, Steward, which owns more than 30 hospitals in the country including eight in Florida, had announced plans to use a $150 million loan to pay bills and sell assets to raise cash, including two corporate jets, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Steward’s executives are framing the bankruptcy process as helping to improve hospital operations and assist the company in paying off debt. Steward has indicated in court records that several buyers have shown interest in its hospital operations in Massachusetts, Arizona and Texas, and they have “generated interest” for hospitals in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Arkansas and Louisiana. Steward has also “launched a market solicitation process” for its Florida hospitals to “explore a sale or reorganization around such hospital operations.”

“The biggest concerns that we’ve heard is whether or not this hospital [North Shore] is going to stay open or if it’s going to close,” said Canales, the vice president of 1199SEIU. “And if it closes where does that care go? Because we’re not exactly sure that the surrounding hospitals would be able to absorb the need that is in that community.”

Why did Steward Health file for bankruptcy?

In 2021, Steward Health bought North Shore and four other South Florida hospitals — Coral Gables Hospital, Palmetto General Hospital in Hialeah, Florida Medical Center in Lauderdale Lakes, and Hialeah Hospital — from Tenet Healthcare for $1.1 billion. Steward also owns three other Florida hospitals — Melbourne Regional Medical Center, Rockledge Regional Medical Center and Sebastian River Medical.

That year, Steward sold all of its South Florida real estate to Medical Properties Trust, which the Wall Street Journal says is the nation’s largest hospital landlord, and is now paying rent to operate its hospitals on the properties it used to own, according to financial documents the Miami Herald obtained through a public record request with the state. It did the same thing with its other hospitals across the country.

In a statement, Steward’s CEO, de la Torre, said the company decided to declare bankruptcy because of rising costs and the delay in finalizing the sale of its nationwide physician network to Optum, a subsidiary of United HealthGroup. He also blamed “insufficient” reimbursement rates by Medicare and Medicaid, “skyrocketing labor costs, increased material and operational costs due to inflation, and the continued impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Some have criticized de la Torre for his lavish lifestyle while his healthcare empire sinks. He owns two yachts, a Dallas mansion in the same neighborhood as former U.S. President George W. Bush and businessman Mark Cuban, and two luxurious private jets, one of which is the Bombardier Global 6000, the same jet that helped Taylor Swift make it back to the U.S. from Tokyo to watch her boyfriend win the Super Bowl, according to the Boston Globe.

The health executive, in emails to the Globe, denied allegations that he allowed Steward’s community hospitals to whither to support his lifestyle.

Steward has more than $1 billion in debt, though it’s difficult to know how the hospital system’s individual hospitals are doing financially. Steward has had a long-standing dispute with Massachusetts officials for going against a state rule and keeping its financial information a secret for years. It’s held a similar practice in Florida.

The hospital system has not submitted audited financial statements and reports to Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration, as required by state law, for at least North Shore and Palmetto General Hospital since Tenet sold the hospitals to Steward in 2021. The Miami Herald learned this while making a public record request with the state agency for each hospital’s financial records.

De la Torre told South Florida staff that Palmetto General Hospital and Florida Medical Center, 5000 W Oakland Park Blvd in Lauderdale Lakes, had their best two quarters so far, according to people who attended the meetings. Steward’s attorney also said in court that its Florida hospitals were the “most profitable,” according to Fierce Healthcare. Steward will not be able to keep its finances a secret in court.

For now, North Shore, Palmetto General, Coral Gables, and Steward’s other Florida hospitals remain open. Doctors are still caring for patients and the emergency rooms remain open.

North Shore leaders declined to be interviewed by the Miami Herald. Pague, the Steward spokeperson, told the Herald in an April email that “there are no plans to reduce any other services” at North Shore.

But the closing of North Shore’s labor and delivery unit — a service that doesn’t bring in a lot of money to hospitals — has left the community grappling with the loss.

Many have flocked to Jackson North Medical Center and the Women’s Hospital at Jackson Memorial’s main Miami campus. Jackson Health has quieted rumors that it’s looking to buy North Shore, but it is ramping up its labor and delivery services to ensure it can meet demand.

Jackson North, 160 NW 170th St, has seen a 15% to 30% increase in patients coming to the center for labor and delivery services since North Shore cut back on care, according to Dr. Marie Sandra Severe, Jackson North’s CEO and senior vice president. Its neonatal intensive care unit is also seeing more babies.

Joanne Ruggiero, CEO and senior vice president of Holtz Children’s Hospital and the Women’s Hospital at Jackson Memorial, says the hospital system has homed in on Black maternal health. For the past several years, Jackson has worked to reduce the medical mistrust that is in South Florida’s Black communities, through outreach efforts and building partnerships with doulas, midwives, birthing centers and other health providers, she said.

“All of our work has really had a focus on disparities of care and making sure that we eliminate them within our hospital and the North Shore closure actually really gave us a chance to test the work that we’re doing and what we’re able to see is that we actually did have the right infrastructure in place” to support more patients, Ruggiero said.

Both Jackson CEOs say their hospitals can care for women through the entire pregnancy, including postpartum, and are looking to expand operations and provide more services. They’re also focusing on natural childbirth to increase birthing options for patients. Ruggiero said all of Jackson’s hospitals are using wireless monitors so expecting moms who want natural childbirth can walk around. Severe says Jackson North is also planning to open an obstetric ER in the next few months, and if all goes well, offer water births at the center by 2025.

Jackson has also partnered with the Southern Birth Justice Network to get doulas into its hospitals to help support expecting parents.

‘Beacon of light’

South Florida health providers say the goal is to ensure expecting patients have a variety of birthing options in South Florida, something that proved critical for Marie Gilliam, 37, of Cutler Bay.

“I know the severity of what it means to give birth in America as a Black woman,” Gilliam told the Miami Herald. “You’re not really heard ... so I wanted to make sure that I was in a place surrounded by people who would care for me as a person and want the best outcome for me.”

A bad experience at Jackson South for a spinal injury made her want to give birth at home. The midwives and doulas she found through the Southern Birth Justice Network were a “beacon of light” on her journey, she said.

But two weeks before her due date, Gilliam began to show signs of preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication associated with high blood pressure. Plans changed — and she gave birth in North Shore.

It wasn’t a pleasant experience. Gilliam said she argued with inattentive nurses who didn’t acknowledge she was in labor until 30 minutes before her daughter was born. The doctor didn’t make it to the birth, but showed up shortly after her baby was born.

And then, finally, Gilliam’s dream — to be a mother — came true.

Amarna-Marie Massey was born 12:58 a.m. June 4, weighing 6 pounds and 3 ounces.