Why doesn’t the Pacific Northwest get hurricanes? We asked a meteorologist

When Category 4 Hurricane Ian plowed into southwest Florida on Wednesday, it became the sixth hurricane of at least that strength to make landfall in the United States since 2017.

Ian also became the 46th Atlantic Ocean hurricane to achieve at least Category 4 status since the turn of the century, with many making landfall in the U.S.

#GOESEast captured this incredible view of the inside of #Hurricane #Ian's eye as the storm approached Florida.

Latest: https://t.co/FYrreOueMf#FLwx pic.twitter.com/ulAYnrtw9z— NOAA Satellites (@NOAASatellites) September 28, 2022

It’s now been seven years since the U.S. enjoyed a year in which no hurricanes hit the continental U.S., and there have been only 16 years where the U.S. has had that luxury.

As active as the Southeast is during hurricane season, why does the Pacific Coast not bear the brunt of ocean-borne storms?

Before you think, “Why does this matter in Boise?” — well, the City of Trees is approximately 400 miles inland from the Oregon coast.

Hurricane Ida made landfall in southeast Louisiana last year and was still causing damage as an extratropical low in New York City, approximately 1,200 miles away. A couple of years earlier, Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas and caused flash flooding in Greeneville, North Carolina, about 1,000 miles away.

Boise might not be close enough to the coast to be hit by strong winds from an ocean storm, but it would be close enough to feel the heavy after-effects of extratropical cyclones.

Hurricanes enjoy the warmth

As you might guess, the primary reason the Pacific Northwest doesn’t get hurricanes is that the storms use warm water as fuel, Korri Anderson, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Boise, told the Idaho Statesman.

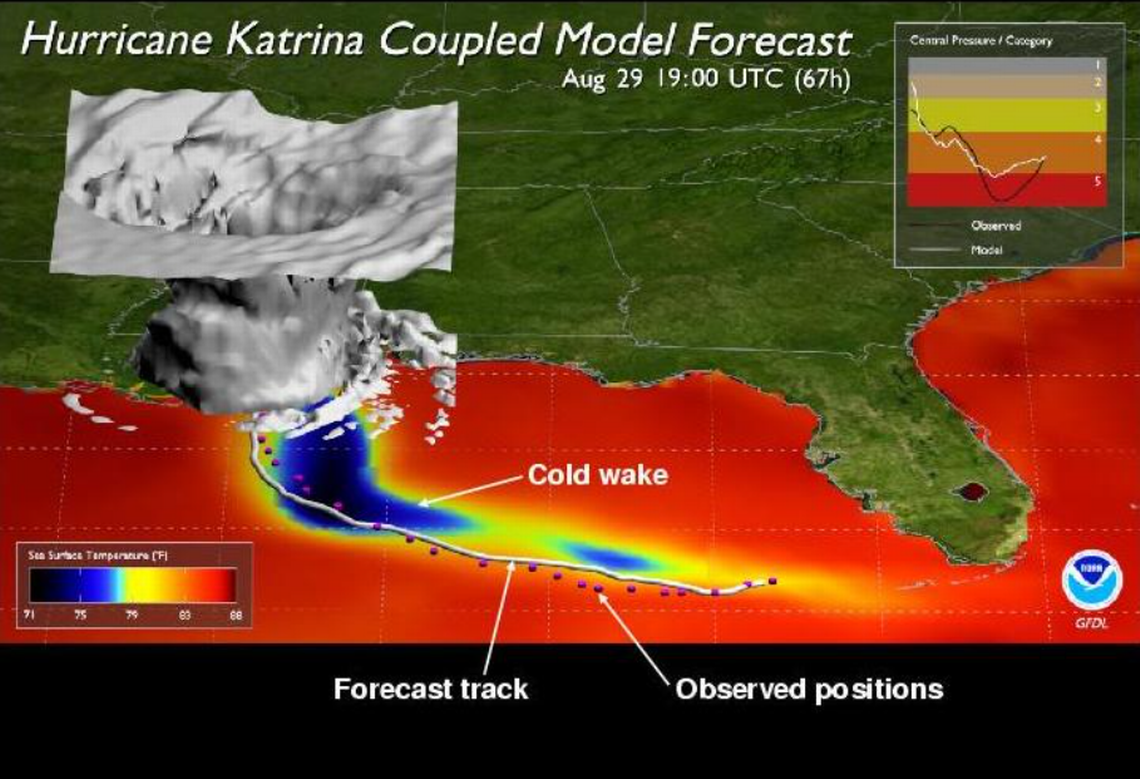

Warm water is vital for hurricanes because that’s how they get energy, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hurricanes typically strengthen over warm water and leave cooler water in their wake, according to NOAA, which is why it says global warming and rising sea temperatures will contribute to stronger and more frequent hurricanes in the future.

Surface-level sea temperatures have to be at least 80 degrees for a hurricane to form, Anderson said. The ocean waters along the West Coast are typically a chilly 50 to 65 degrees.

“Pretty much anywhere north of Hawaii to Alaska is too cold to have tropical systems,” Anderson said. “On the other side of the ocean in the western Pacific, you can get that warm water all the way up to Japan.”

That’s not to say tropical storms can’t form in the northeast Pacific every now and then. In 1975, a nameless hurricane formed from the remnants of Hurricane Ilsa northeast of Hawaii. The storm became the farthest-ever north Pacific hurricane and came close to the coast of Alaska, but it failed to make landfall after colliding with a cold front and falling apart.

Why is the water so cold off the West Coast?

It might make sense why water off the coast of Washington and Oregon would be chilly, but cold water persists all the way south to Cabo San Lucas at the tip of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula.

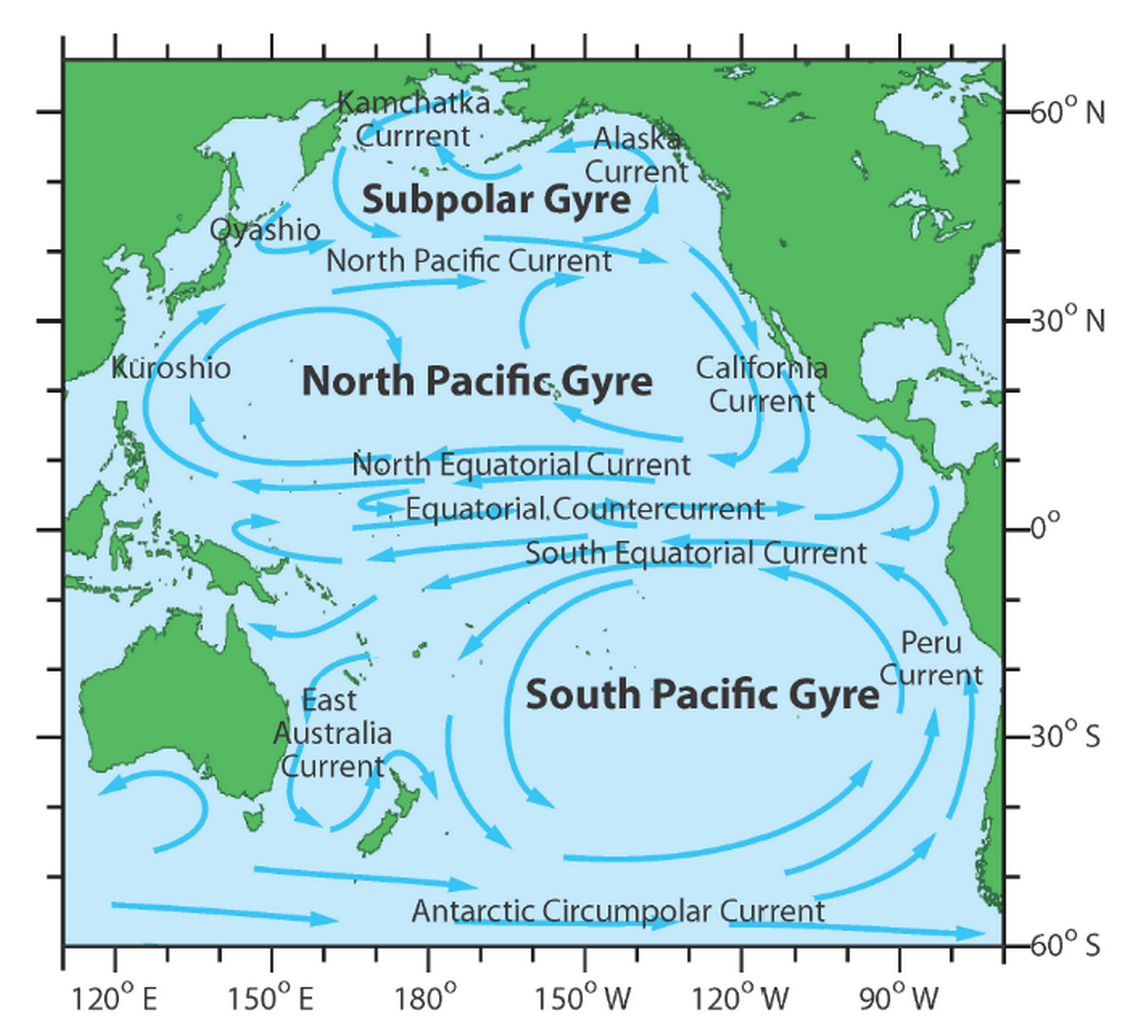

Cold water reaches that far south because of the North Pacific Gyre, a large rotating system with smaller rotating systems within it.

One of those smaller systems is the California Current.

“You get the westerly flow,” Anderson said, “and it makes the currents come down from Alaska, and it flows down towards Baja California.”

The cold water from Alaska is then pushed westward as it collides with warmer water from the North Equatorial Current and flows across the Pacific, until it reaches near the east coasts of Asia.

The water warms as it crosses the world’s biggest ocean, which is why typhoons — the name for a hurricane in the western Pacific — occur in the western Pacific but not in the eastern pacific.

The same phenomenon occurs in the Atlantic — the North Atlantic Gyre pulls water from northern Europe toward the African coast before pushing it west toward the Americas. Along this warm-water current, hurricanes form.

Wind also affects a hurricane’s path

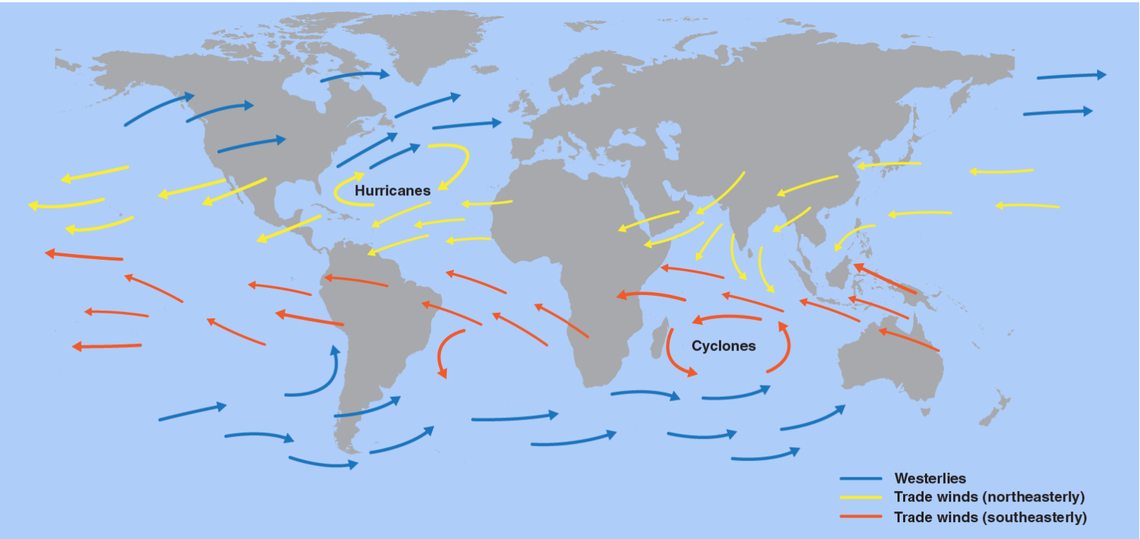

Another primary reason why hurricanes mostly move from east to west — and therefore away from the U.S. West Coast — is because of trade winds. Trade winds result from the Coriolis Effect, the phenomenon that causes the worldwide circulation of wind that is created as the Earth rotates.

In most of the Northern Hemisphere, these trade winds blow from the northeast to the southwest, eventually blowing more easterly as they approach the equator.

Some trade winds — called westerlies — occur close to the poles and blow in the opposite direction. These winds, on rare instances, can blow storms back toward Europe, such as Hurricane Katia in 2011, which formed east of Florida, traveled north and eventually hit the United Kingdom.

Along with following the flow of warm water, hurricanes are typically pushed westward by these winds.