Will Royals’ $2B downtown stadium district be worth it for Kansas City? It’s hard to say

Kansas City Royals CEO and chairman John Sherman, the head of the franchise’s ownership group, made his first public case for the team to move into a downtown ballpark in an open letter earlier this week.

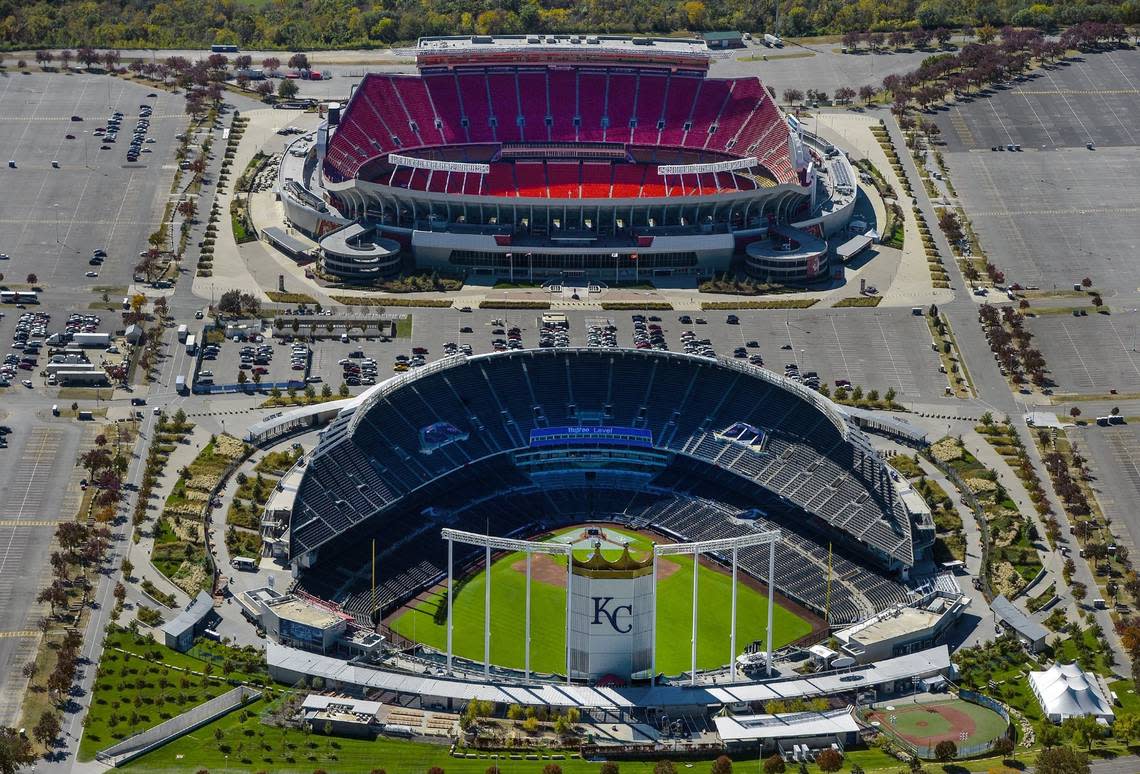

Previously, his comments had been measured and often referred to the team as “exploring” and/or “studying” a potential move from the Truman Sports Complex into downtown KC.

Along with taking a definitive stance that the club and region will be better off with the Royals downtown, Sherman presented some specific dollar figures: the project’s estimated cost and the projected economic impact of a ballpark district. And that may have been the defining characteristic of the three-page letter.

Sherman placed a $2 billion price tag on a proposed “ballpark district” that would include a stadium, restaurants and shops, office spaces, hotels and housing, including affordable housing options. He also said the Royals would work with local officials to ensure adequate public-transportation options.

The benefits for the local community, according to the letter, would include approximately $185 million more in regional economic output than currently created by Kauffman Stadium. Sherman also claimed the district would lead to greater regional visitation that will sustain more than 600 new jobs and spending that will spur $60 million in new tax revenue over the first decade.

The economic impact of the proposed Royals downtown ballpark district will likely warrant further discussion, involve varying assessments and provide a topic of rigorous debate.

Where did these figures come from?

The source of those figures wasn’t made clear in Sherman’s letter, but the Royals later said the research Sherman cited was done by an outside firm, HR&A Advisors.

It was not a study carried out by the Royals nor one of the several architectural or design firms that could potentially play a role in the construction of the ballpark district.

HR&A has offices in New York, Atlanta, Dallas, Los Angeles, Raleigh, and Washington DC, and markets itself as a company that turns real estate, economic development concepts and public infrastructure into actionable plans.

Similar economic impact elsewhere?

While no two situations will be exactly the same because of myriad factors, including changing economic conditions, it’s worth considering what type of documented impact other ballparks have had in recent years.

The San Diego Padres moved roughly seven miles from what was at the time Qualcomm Stadium in a more suburban setting — with a sea of surrounding parking — to downtown San Diego and into Petco Park, a $453.4 million project that opened in 2004.

In July 2010, Conventions, Sports & Leisure International conducted an assessment of the economic and fiscal impact of the Petco Park project.

CSL’s report included estimates of the spending within the local economy directly related to the presence of the Padres, the ballpark and the surrounding development, such as residential units, hotels and commercial and retail spaces. The report estimated the project brought in approximately $2.6 billion between 2003 and 2009, including approximately $1.3 billion in new spending, to the local economy.

The estimated new economic output during that span included almost $2 billion, 19,200 jobs and $780 million in earnings.

The estimated amount brought in by sales, transient occupancy and property tax revenues from 2000 to 2009 by the City of San Diego has surpassed $207 million. Approximately $110 million of that tax revenue had been retained by the City of San Diego and the Centre City Development Corporation, according to the report.

Measuring economic impact can be a murky endeavor

For years, Kennesaw State professor and economist J.C. Bradbury has pushed back against the supposed economic impact of multi-million-dollar sports stadiums and venues.

He’s maintained that most projected economic impact figures come from proponents of the stadiums themselves.

In Cobb County, Georgia, the Atlanta Braves MLB franchise makes its home at Truist Park in suburban Atlanta at The Battery entertainment district.

County officials claimed that Truist Park and The Battery made more than $34 million during the Braves’ World Series championship season in 2021, and property values at The Battery increased by $43 million from 2020 to 2021.

Bradbury released a study of his own claiming that, despite an increase in sales-tax revenue, a large chunk of that spending came at the expense of existing businesses in the county.

He also asserts that the property value growth for the area surrounding The Battery has been typical for the Atlanta region and rejects the presence of the ballpark as a major contributing factor.

Bradbury claims that stadium-related tax revenue for Truist Park fell short of the public funds invested in servicing stadium debt to the tune of a $14.6 million loss per year in 2018 and 2019 (pre-pandemic years). That comes out to an approximate cost of $50 per household, Bradbury concluded.

In the aftermath of Bradbury’s report, noted economist Andrew Zimbalist published a paper that deemed a 2018 Georgia Tech Center for Economic Development Research report “unrealistically optimistic,” and also described Bradbury’s report as “too pessimistic.”

A professor at Smith College who has studied the economic impact of sports venues and written extensively for decades on the topic, Zimbalist concluded the Braves’ project will be “a significant fiscal plus.”