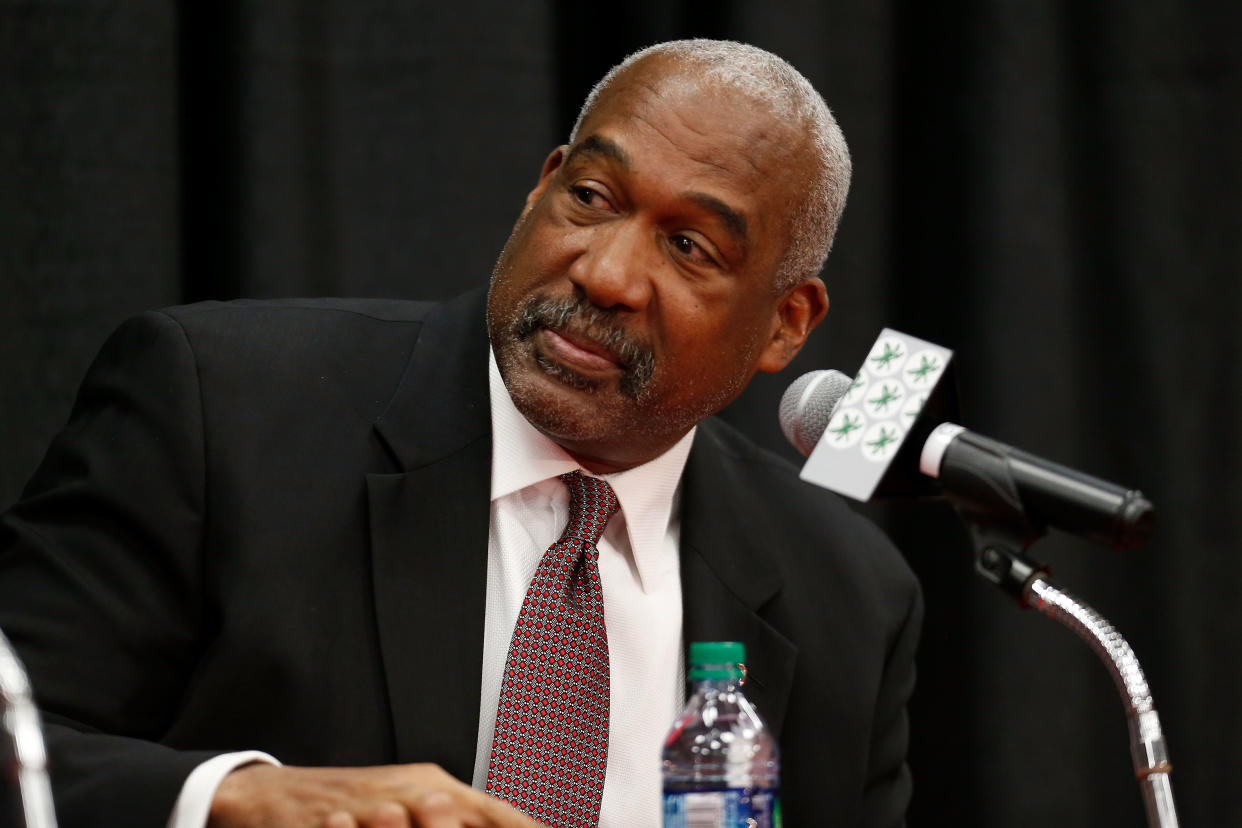

While Congress dithers on NIL, Ohio State AD Gene Smith has his own idea on how to solve issues

WASHINGTON — In 1986 at the age of 29, Gene Smith became the athletic director at Eastern Michigan. He’s 67 now in his final year in the industry, he told a U.S. congressman Wednesday.

“Trust me,” he said, “I never wanted to come to the federal government to ask for help.”

Yet, here he was Wednesday, a witness in a hearing before a congressional committee exploring name, image and likeness (NIL). The uneventful, two-hour event served as another chapter — a ninth hearing — in a now four-year campaign from college leaders to encourage lawmakers to pass a uniform NIL bill.

Afterward, away from hearing-room cameras and removed from the witness microphones, Smith took a deep breath and revealed his own proposal for athlete compensation. In an interview with Yahoo Sports, Smith outlined what he calls a fix to an issue that administrators say has rocked college sports: Change scholarship rules to permit more revenue to funnel to athletes.

“Some people believe the money (to athletes) should flow through the institution. I’m not one of them, unless we settle on a new scholarship model,” said Smith, in his 18th year as Ohio State’s athletic director. “We give room, board, tuition, cost of attendance and [Alston v. NCAA] money. What you’d do is add to the scholarship model an amount of dollars for NIL money.”

Such a proposal isn’t unheard of. It’s been whispered through college sports circles for months as a way to direct more resources to athletes — a concept even discussed, however briefly, in the NCAA Transformation Committee talks last year.

Smith is uncertain about the details of his idea. In theory, the plan would permit schools to create licenses for athletes who could then determine what school-related NIL endeavors with which they wanted to be involved.

He envisions a student board of directors to design such endeavors. Athletes would be permitted to strike other NIL deals with brands, other entities and possibly collectives.

“They can do other things,” Smith said. “We’d be able to help them settle deals. If you’re an athlete majoring in actuarial science and there is a company in Cleveland, I can take you up to Cleveland and I can take you up and help introduce you to the CEO and say, ‘Hey, can you do a deal with him and make sure he gets a good experience?’”

Smith’s idea would bring to a close the ongoing debate as to how involved schools should be with NIL. Current NCAA rules and even some state laws feature restrictions that limit a school’s involvement in arranging or striking NIL deals for and with athletes.

The NCAA NIL working group, in its fourth year of existence, has been re-exploring more permanent concepts to implement around NIL, including Smith’s idea of tightening the relationship between school and NIL.

However, such an idea raises legal questions. Some believe that the entire economic models around college sports would need to fundamentally change for it to work. The extra pay to athletes could be viewed as another trigger to athletes being deemed employers of their universities — an issue that college administrators vehemently push against and one that the NCAA is fighting in court.

In examining more permanent NIL policies, the working group is already receiving pushback from the NCAA’s legal counsel.

“We’re trying to do some stuff. Some of it will solve these issues, but we’re so diverse in our thoughts across the country,” Smith said. “Some of us want to do certain things and some don’t. We’ve got legal giving us warnings why we can’t do something. There are some things you take a business risk on. You can do them, but you’re taking the risk.”

The working group hopes to standardize NIL contracts, provide a registry or certification system for NIL agents and potentially hire a third-party administrator to create a public database pooling NIL contracts.

While those things “move the needle,” they won’t result in a “significant impact,” Smith said.

What will? Changing the scholarship model, he said.

In his model, could athletes still strike NIL deals with collectives? Smith played coy.

“I’ll leave that to your imagination,” he said smiling.

Collectives were a central topic during Wednesday’s hearing before the House Committee on Small Business. Witnesses referred to donor-led collectives as “largely fan clubs,” and one lawmaker ripped the groups as using “hocus pocus” while operating around Title IX.

Several leaders of various collectives have formed The Collective Association (TCA), a group of 21 collectives across the country. Some TCA leaders made the trip to Washington, D.C. for the hearing. Seated on the front row, they often bristled during discussions about their industry.

Afterward, Hunter Baddour, representative for TCA and co-founder of Tennessee's Spyre Sports Group collective, provided Yahoo Sports with a statement: "We learned during Wednesday’s hearing that there is a fundamental misunderstanding — or deliberate discounting — of what our collectives can bring to the table to help student-athletes across the board. We look forward to the opportunity to bridge that gap with constructive, professional dialogue going forward."

Meanwhile, federal lawmakers continue to work toward a compromise over NIL legislation. At first thought to be a bipartisan issue, the matter has divided an already splintered U.S. Senate, where legislative action is expected to begin.

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) is working with Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) and Cory Booker (D-NJ) on a unified bill to push through the Senate Commerce Committee, where Cantwell is chair and Cruz is ranking member.