Weaver or Ellis? SC voters to decide new schools chief and direction of public education

The race for South Carolina schools chief between Republican Ellen Weaver and Democrat Lisa Ellis pits two first-time candidates in a contest that could have major implications for the future of public education in South Carolina.

The candidates share many of the same priorities, such as raising teacher pay, improving school mental health services and encouraging more parental involvement in schools, but have starkly different political ideologies and backgrounds, and present contrasting visions for achieving their policy goals.

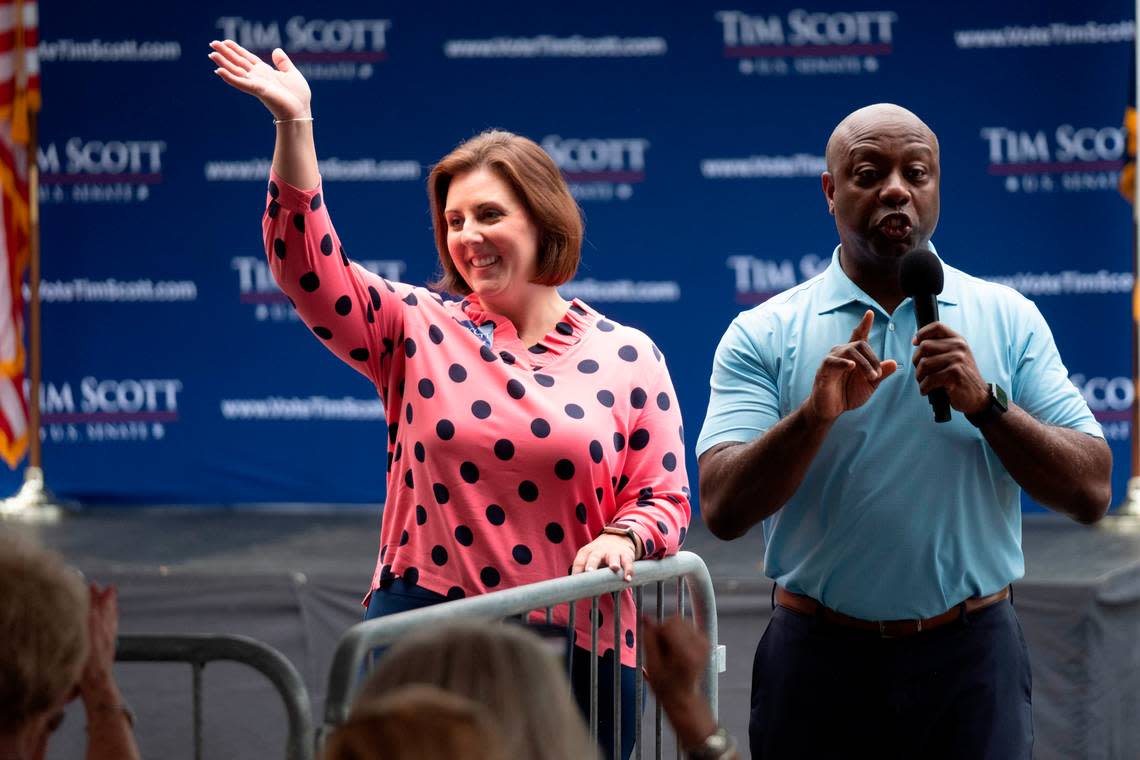

Weaver, a longtime aide to former U.S. Sen. Jim DeMint and president of the Palmetto Promise Institute, is a well-funded political insider with no teaching experience but deep-rooted relationships with Republican lawmakers and years of policy experience.

A darling of the national school choice movement, Weaver smashed fundraising records on her way to a Republican primary runoff victory over Kathy Maness, the leader of South Carolina’s largest teachers advocacy organization.

Ellis, a Richland 2 student activities director and founder of grassroots teachers group SC for Ed, is a political novice who has spent more than two decades in the classroom and understands firsthand the challenges that teachers in South Carolina face.

She came to prominence in 2019 after SC for Ed successfully channeled widespread discontent over teacher pay and working conditions to galvanize a historic march at the State House.

Both candidates say they want to ensure all children in South Carolina are afforded the opportunity for a quality education, but would go about doing so in very different ways.

Weaver is one of the state’s most vocal champions of private school choice, arguing that all children deserve an education that meets their individual needs, be it public or private.

Her think tank, Palmetto Promise Institute, has for years been at the forefront of the education choice movement in South Carolina, pushing for legislation that would allow families to pay for private schools with public dollars.

Ellis is a staunch opponent of private school choice who believes taxpayer dollars should remain in public schools. She supports more funding for public education and said she fears Weaver and her supporters in the school choice movement want to destroy public education.

“I don’t think you could get more opposite in terms of what my opponent and I stand for,” Ellis told The State Media Co. in July.

Campaign donations plainly illustrate the disparate bases of support each candidate has cultivated.

Weaver, the recipient of more than $740,000 in campaign contributions, a state superintendent contest record, is funded primarily by big-dollar donors from the worlds of business, finance and school choice. Less than 1% of her donors identify as educators, according to campaign finance data.

By contrast, Ellis has gotten four times more individual donations than Weaver, but has raised just $227,000 because she averages only $51 per donation to Weaver’s $740. She counts educators as her largest contributors.

The race between Weaver and Ellis has been less contentious than the hotly contested Republican primary, but has touched on many of the same themes.

Weaver has toned down some of the divisive rhetoric she employed against Maness, but continues to home in on wedge issues, such as critical race theory, COVID-19 protocols and transgender student rights, that play to the Republican base.

“I’m the only candidate who supports school choice, supported reopening our schools, and opposes woke indoctrination,” her campaign posted on social media earlier this month in promotion of “Far Left Lisa,” a website paid for by the South Carolina Republican Party that paints Ellis as a “progressive champion” with a “radical” record.

Ellis has been less confrontational, opting primarily to tout her own strengths rather than attack Weaver’s academic credentials, but, like Maness, has questioned the legitimacy of her opponent’s master’s degree and the Republican Party’s decision to certify her candidacy before she met the qualifications for the office.

By law, South Carolina’s top schools official must, at minimum, possess a master’s degree and “substantive and broad-based experience” in public education or financial management.

Weaver, who enrolled in an online master’s program sometime in April and roughly six months later announced she’d completed her coursework, has criticized the focus that’s been paid to her master’s quest.

“People are looking to hit me because they don’t frankly have anything else to go after,” she said. “They’re trying to make an issue when there isn’t one.”

Regardless of who comes out on top Nov. 8, the state’s next superintendent of education is likely to take the office in a different direction than current schools chief Molly Spearman, who opted not to seek a third term.

Spearman, a moderate Republican who recently endorsed Weaver to the chagrin of many public school teachers, has taken a measured approach when dealing with politically polarizing issues that her eventual successor appears less likely to adopt.

Weaver and Ellis will square off in a televised debate at 7 p.m. Wednesday on South Carolina ETV.

Who is Ellen Weaver?

Weaver is a 43-year-old Greenville native with a long career and many connections in Republican politics, but no classroom teaching experience.

After graduating from Bob Jones University in 2001 with a degree in political science, she went to work for DeMint in Washington, climbing the ranks from executive assistant to state director of his Columbia office.

When DeMint resigned in 2013 to head up the Heritage Foundation, he used $300,000 in leftover campaign cash to launch Palmetto Promise, a free-market policy research institute focused on education and health care issues, and tapped Weaver as its president and chief executive.

She has served in the role ever since, focusing primarily on education issues, but also weighing in to oppose Medicaid expansion and push for income tax relief.

In 2016, Weaver was appointed to the South Carolina Education Oversight Committee, which approves academic content standards and assessments and works with the Department of Education to develop school and district report cards. She chaired the committee from 2019 to 2021, but resigned her leadership post after getting into the superintendent race.

While Weaver waded heavily into divisive culture warrior rhetoric in her primary campaign, she has of late emphasized her willingness to listen to and work with others toward shared goals.

“I think the best approach to leadership is to be thoughtful, listen and learn,” she told The State earlier this month. “Over the next few months I plan to do exactly that, to speak with Superintendent Spearman and understand the processes and divisions within the (education) department and get a lot of counsel and feedback.”

In recent interviews, Weaver has fashioned herself a relationships-oriented leader who excels at balancing the interests of a variety of stakeholders and translating ideas into action. On the stump, she frequently highlights her policy experience and constructive relationships with governors and state lawmakers.

“I see myself as a common-sense bridge builder,” Weaver said earlier this week before a campaign fundraiser in Charleston. “There are so many people who have to be on the same playbook if we are actually going to move the ball forward. And I believe that’s the unique skill set that I bring to this job, and the reason why I’m honestly the only qualified candidate.”

When knocked for lacking teaching experience, Weaver points to her executive leadership and management skills that she says will be invaluable for running the Department of Education’s multibillion-dollar operation.

“I am not running to be a classroom teacher,” she said. “I am running to put the experience that I have had in over 20 years of public service to work on behalf of the students, the parents and the teachers of this state.”

As superintendent, Weaver has promised to “repair South Carolina’s broken education system” by emphasizing early literacy — she previously served on Spearman’s Read to Succeed advisory panel — enhancing school safety and engaging parents in the education process.

She wants to raise teacher pay, take unnecessary paperwork off of educators’ plates and foster professional learning communities for teachers and administrators that elevate instruction and instill strong school culture.

A self-proclaimed “unapologetic supporter” of school choice who has advocated for taxpayer-funded scholarship accounts that families can tap to pay for private school costs, Weaver has said she would implement and administer any school choice program the General Assembly passes.

She’s also supportive of legislative efforts to clarify what can and cannot be taught in South Carolina public schools. The General Assembly last session failed to pass a critical race theory ban after struggling to coherently define the term, but could take up the issue again in the new year.

“We are about education, not indoctrination of any stripe,” said Weaver, who added it was important teachers and administrators know exactly what is expected of them so they don’t have to guess about the Legislature’s intent.

In order to enhance school safety and improve discipline, Weaver supports placing a resource officer in every school and has floated the idea of allowing military veterans to serve in that capacity.

She’s also voiced support for Gov. Henry McMaster’s efforts to increase the number of school mental health counselors. The governor earlier this year tasked the Department of Health and Human Services with expanding school mental health services after an audit found counseling was available in less than half of the state’s public schools.

The lack of mental health support in schools is the most frequent concern Weaver said she hears from educators.

“If we are going to get ahold of the teacher retention issues, it really is going to start with the questions of mental health support and restoring discipline in the classroom where that may be lacking,” she said.

While Weaver supports raising teacher pay, she hasn’t supported increasing overall education spending. South Carolina is not underfunding education, she argues, but misfunding it.

“We have too much money that is siphoned off into programs that maybe 30 years ago were a good idea, but just aren’t serving the needs of our students today,” she said.

For all of Weaver’s talk of her leadership ability and connections, the most salient issue in the superintendent’s race, which has overshadowed the bulk of her policy prescriptions, has been her lack of qualifications for the job.

The South Carolina Republican Party certified her candidacy earlier this year despite her lack of an advanced degree, attesting that she’d earn one by Election Day.

Weaver subsequently enrolled in an online master’s program in educational leadership at Bob Jones University, her alma mater, that she completed in roughly six months while running Palmetto Promise and maintaining an active campaign schedule.

“It’s really been non-stop,” she told The State earlier this month, shortly after announcing she had completed her master’s coursework. “It’s definitely been an intense few months.”

Critics have questioned Weaver’s ability to earn a master’s in such a short period of time and accused Bob Jones of allowing her to cut corners.

The university has denied it gave Weaver special treatment, but unanswered questions about her enrollment date, high course load and capstone research project, as well as President Steve Petit’s public support of her candidacy and campaign donations by several Bob Jones employees have fueled speculation that Weaver’s degree is tainted.

The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, an accrediting body for universities in the southern United States that was inundated with complaints about Bob Jones’ handling of Weaver’s situation, this summer opened an investigation into the school’s policies.

Weaver has denied receiving preferential treatment and said it defied reason that Bob Jones would jeopardize its reputation and accreditation for her sake.

Who is Lisa Ellis?

Unlike Weaver, who has worked in and around politics her entire adult life, Ellis is a reluctant politician.

The 47-year-old Columbia resident said she threw her hat in the ring only after being unable to find anyone else willing to run for state superintendent.

“For two years I tried to find someone else to run for this position because I don’t want to leave the classroom,” said Ellis, who jokes that her goal is to fix education in four years so she can get back to teaching.

Over the course of her career, Ellis has worked as a teacher, instructional facilitator and student activities director at four middle and high schools in Richland and Fairfield counties.

She was thrust into the spotlight in 2019, after a private Facebook support group she created for disaffected teachers ballooned in popularity and galvanized 10,000 educators and their allies to travel to Columbia to demand better pay and working conditions.

Three years later, SC for Ed is a tax-exempt social welfare organization that boasts more than 34,000 members on Facebook, endorses political candidates and releases an annual legislative agenda.

Ellis stepped away from the group in June to focus on her campaign, but has continued working at Blythewood High School, where she teaches a service learning class that aids students in creating and implementing schoolwide events. As part of her job, Ellis recently spent the better part of five days in Florida accompanying students to the annual Southern Association of Student Councils conference.

While the trip prevented her from meeting with voters during a critical stretch of the campaign, she has no regrets.

“I always told my campaign team that my job and my students would come first,” Ellis said prior to the conference. “This is a great opportunity for my students to get to network with other student councils across the other southern states of the U.S.”

Like Weaver, Ellis has maintained a grueling schedule in recent months balancing her full-time job with campaign duties.

She works with students during the day and often after school in her role as student activities director. In evenings and on weekends, she’s in campaign mode, traveling to events and meeting with voters or doing media interviews.

Ellis said she’s managed to juggle both roles relatively successfully, but has on occasion had to turn down opportunities to meet with constituents due to school obligations.

“I’ve really worked hard to make sure, first and foremost, that my students and school haven’t suffered because they deserve everything I can give them,” Ellis said. “It has really been helpful for me to remain in the school, to be reminded of what the issues surrounding public education are and just to sort of keep me grounded in what I’m fighting for.”

For Ellis, the issues that inspired thousands of teachers to march on the State House in 2019 are the same ones that animate her superintendent campaign: increasing teacher pay, improving working conditions, limiting class sizes and reducing standardized testing.

Minimum starting salaries — which the General Assembly raised to $40,000 this year — must increase substantially if the state wants to recruit and retain talented educators, she said.

And the goal cannot simply be to reach parity with the southeastern average, as some lawmakers have proposed. If South Carolina wants to attract teachers, Ellis said, it will need to pay them enough that they turn down jobs in other more lucrative fields.

“The General Assembly … doesn’t realize the reality of the market today, because you’re no longer competing against just other jobs in education,” she said. “You’re competing against every other job that exists.”

She said South Carolina’s ever-growing shortages of teachers, bus drivers, instructional assistants and school mental health counselors speak to the fact that lawmakers don’t understand how education works in 2022 and aren’t doing what’s necessary to fix the problem.

In addition to increasing teacher salaries, Ellis also wants more state education funding for mental health counselors, social workers and nurses.

While she acknowledges that some districts spend money in the wrong places, including on central office bureaucracy, she disagrees with Weaver that education in the state isn’t underfunded.

“I don’t think districts are getting enough funding from the state, full stop,” Ellis said. “Because if they were, then we would have access to mental health, we would have smaller class sizes, we would have buildings that aren’t falling down around students.”

Ellis also wants to curb high-stakes testing, which she said drives discontent over working conditions and contributes to teacher turnover. Rather than “one-and-done” testing that creates anxiety for teachers and students, forces teachers to teach to the test and fails to accurately capture student improvement, the state needs to adopt a testing regimen focused on growth, she said.

South Carolina also must reassess its teacher evaluation system, eliminate the pointless hoops educators are forced to jump through and develop a robust mentoring program for teachers entering the classroom, Ellis said.

She’s not opposed to hiring more school resource officers, as Weaver has proposed, but has concerns about perpetuating the school-to-prison pipeline and said she’d only support adding officers in schools if they were focused on building positive relationships with students.

“I can support school resource officers, if you’ve got the right resource officers in place,” Ellis said. “But it’s not the answer.”

Improving school safety and student discipline, she said, will rely on making students feel supported in their schools.

“You’ve got to get adults in the building — teachers, instructional assistants, bus drivers — to build those relationships to make that student feel connected to the school,” she said.

Until better academic supports are in place and children have access to hot meals and mental health services, “you’re just putting Band-Aids on a broken dam,” Ellis said.