Watch the teeth! Hands-on shark research in Lowcountry may one day help cure human illnesses

For nine days in March, Will Crowson and a team of researchers waited with baited breath.

Sometimes, in the crew area of an old 126-foot crabbing boat retrofitted for shark research, they waited for storms to blow through. Other times, when the angry clouds cleared, the team of about two dozen moved to the deck vying for one of the ocean’s apex predators.

On Day 10, in crystal clear water, they found what they were looking for: great white sharks.

At about 10 feet long, the juvenile white shark circled the boat for about two hours before researchers pulled it up in a lift. Crowson, a biology major at University South Carolina-Beaufort, shook off his jitters and stared in amazement.

“The kid in me was screaming,” he said.

But he wasn’t there to gawk. He knew this. Once the researchers put the shark on a lift, the work started. They didn’t have much time. Just 10-15 minutes to get the samples, measurements and tags the catch required before the release.

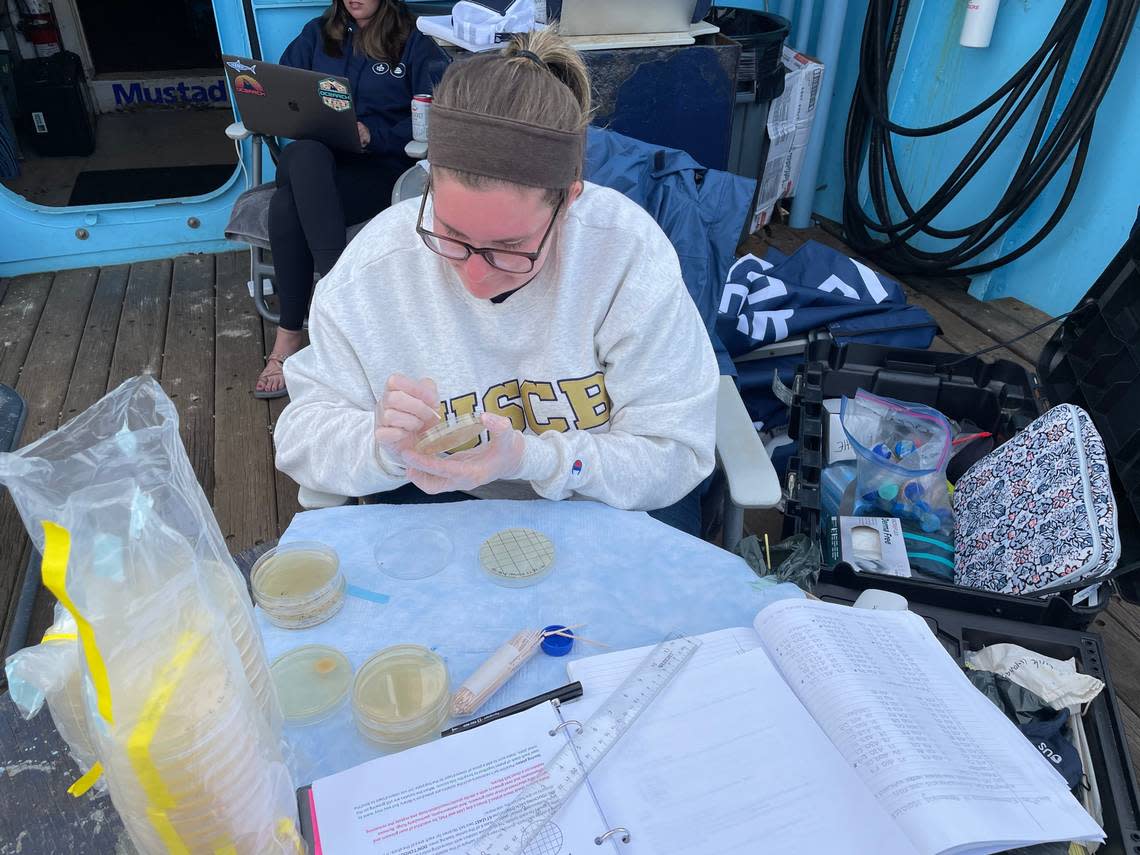

After cotton swabbing the white shark’s nostrils, teeth, gums, dorsal fins, and cuts and wounds, Crowson delicately swiped the swabs onto agar-filled Petri dishes so he and USCB professor Kim Ritchie could watch the bacteria cultures grow.

Ritchie’s research looks at beneficial bacteria specific to white sharks that is antibiotic producing. Sharks are a bit of enigmas this way — they heal their wounds quickly, and cancer is rare in great whites. She’s curious about the bacteria on and around them that protect them and how it may be able to help humans who are resistant to current antibiotic treatments or, in a rare case, are bitten by these sharks.

Her current work is backed by OCEARCH, a global nonprofit that conducts research on sharks, whales, seals and turtles by tagging, tracking and swabbing samples from the animals. The over 100-foot-long crabbing boat? That’s OCEARCH’s marine lab. The crew is made up of people from all over the United States. And this particular expedition, from March 4-24, focused on the Carolinas.

Crowson is one of the lucky ones.

He was the only undergraduate aboard his 10-day leg of the expedition. Surrounded by interns who were master’s students or PhD candidates, the then-first semester senior might as well have been a fish out of water.

Hilton’s history

Five years ago, Ritchie hadn’t yet traversed into looking for antibiotic-producing bacteria in white sharks. Instead, she and OCEARCH researchers wanted to know the fish’s history in the North Atlantic.

Where did they go to mate, they wondered. Where did they have babies and how long is the gestation period? What about their travel patterns in the winter and summer?

A 12.5-foot-long, 1,300 pound shark, simply named “Hilton” after being tagged near Hilton Head Island, filled in gaps during a 2017 expedition. He was the first male OCEARCH tagged.

“He led us right up to Nova Scotia, and then we started going up to Nova Scotia because of them,” Ritchie said. “And that’s when we figured out the life history of the North Atlantic white shark.”

To bulk up on seals, white sharks head to Nova Scotia in the summertime. In the winter, they haul it down to the Carolinas and even farther south, and researchers believe the fish are mating at that time. After mating, the females act as loners off the Mid-Atlantic ridge for about 18 months. They drop their pups around Long Island, Ritchie said. Those pups stay up there for a few years until they are strong, and then they begin migrating.

All this information off one shark? Yes. Getting a single shark into the OCEARCH lift can feed into 50 different research projects.

“We’ve learned so much, and a big part of that was being able to tag Hilton,” Ritchie said. “He’s kind of the ambassador for the North Atlantic white sharks.”

And that ambassador propelled over 18,000 miles in the two years his tracker held up, said OCEARCH Lead Scientist Bob Hueter. In that time, Hilton went from South Carolina, up to the Grand Banks up Newfoundland, back into the eastern Gulf of Mexico and all the way down to the mouth of the Mississippi River.

The tags that Hueter said are usually good up to 5 years aren’t just pinging on a map to tell the public where the white sharks are located. It’s more precise than that. Scientists can identify water temperatures they like, how deep they swim and their critical habitats important to survival.

For people like Hueter and Ritchie, the importance of their work lies in what many people do not know: White sharks are the balance keepers of the ocean.

“If you eliminate that top level, then the system goes out of whack,” Hueter said. “We’ve had an out-of-whack ecosystem for 30 years. It’s a matter of creating an abundant and healthy ocean again.”

And in the case of Ritchie’s latest research, white sharks may hold what many humans have never given them credit for: A cure.

From fieldwork to lab work

Setting off from Morehead City, North Carolina, for the second 10-day leg of the OCEARCH trip, Tori Sember was ready to throw herself into fieldwork.

The USCB biology senior was used to lab work — analyzing specimens and data inside. But fieldwork meant she got a front row seat in the collection. Aboard the OCEARCH crabbing boat, it became clear that it wasn’t easy, as the boat swayed and the wind whipped, and the environment wasn’t particularly sterile.

Like Crowson, Sember was one of Ritchie’s students. She came on hours after the first crew caught the white shark, but raging storms during her trip meant no such fish were pulled onto the lift.

“Even if you have this perfect picture in your head of how you want things to go, you’re kind of at the mercy of the environment that you’re choosing to work in,” the now-master’s student said.

But once she switched spots with Crowson, she got to plate the bacteria he’d swabbed. The bacteria, notoriously colorful in white sharks, grew in plumes of bright reds and vibrant yellows. Once on common ground, back in Ritchie’s lab, the tedious work began — culturing, growing and testing the samples swabbed from the shark.

Ritchie is interested in beneficial bacteria on white sharks. The fish are older than dinosaurs, trees and Saturn’s rings, the professor said, yet all that time, this type of shark has rarely gotten cancer and has healed quickly without much infection or other issues.

Why is that? It has her focused on the shark’s microbiome — the bacteria on and around them.

It’s a “big area of research all across the board with all animals, including human beings, because we’re starting to realize how important our microbes are for human health or for the animal’s health,” she said.

Ritchie is also looking at antibiotic production in the beneficial bacteria and what it might be doing for the shark. And how it may be able to help human maladies.

“One big problem is we’re running out of antibiotics that work against all of these antibiotic-resistant bacteria (in humans),” she said.

That means searching for novel drugs from novel sources. In this case, white sharks.

The professor has found that about 30% of the bacteria cultured produces antibiotics against something, including MRSA infections, antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospitals and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.

Ritchie’s work also has doctors calling.

When bitten by a white shark, which Hueter said is rare, if the person survives the loss of blood and tissue, infection is the next concern. That’s where Ritchie comes in. She advises doctors on what antibiotics to administer to the patient so they can ward off the infection that comes from bacteria that was introduced into the wound.

“We’re not seeing more bites from white sharks on people, but when it does happen, it’s very serious and she’s helping to perhaps save lives,” Hueter said.

Ambassadors, police and healers

When someone asks Ritchie if she’s afraid of a white shark being pulled up on the OCEARCH lift, she’ll say no every time.

“I’m never afraid, except for the shark. I’m always worried about the shark,” she said.

Even at over 1,000 pounds, she sees the vulnerable animal, surprisingly still in the lift and wants to make sure it’s safe. And she assures, the team always gets the massive fish back in the water without harm.

OCEARCH scientists have to move fast, working up to 15 minutes on the shark to gather the samples they need. They make sure it has enough oxygen. They cover its eyes with a wet towel so it avoids sunburn. They keep water running through the shark’s gills. In a short amount of time, a team of about two dozen has enough data to possibly save lives. And, of course, the white shark population.

It’s been about 60 years since there’s been a healthy number of sharks, Hueter said. From the 1970s through the 1990s, their population was decimated by humans killing the fish, which led to what he called an over-fished ecosystem.

“We’re trying to put things back now, including all the way up to the white shark, which is showing a nice recovery,” Hueter said.

Yes, that means more sharks in the water. However, he warned, this is in no way to say there’s an overabundance of sharks. After all, marine biologists remind us that white sharks are the ambassadors of the ocean. Or, as Sember calls them, “the police.”

And as Ritchie’s research proliferates, the very shark that humans so fear may become our healers.