‘I want to write and I am going to write’: The lost world of Zelda Fitzgerald

Sometime in the early 1970s, Frances “Scottie” Fitzgerald decided to hunt through her parents’ “secret treasures”. The daughter of Zelda and F Scott Fitzgerald was in her fifties when she went up to her attic in Washington on the trail of her literary roots. Rummaging among the scrapbooks and albums, she found a pair of dusty toy soldiers that her father had bought for her in Paris, and a handful of Christmas ornaments “peeling here and there”. But perhaps most revealingly, there were the “lavishly painted” paper dolls her mother Zelda had made for her as a child – “a jaunty Goldilocks, an insouciante Red Riding Hood, an Errol Flynn-like D’Artagnan” – that, 40years later, had barely faded.

“It is characteristic of my mother that these exquisite dolls, each one requiring hours of artistry, should have been created for the delectation of a six-year-old,” Scottie later wrote of Zelda Fitzgerald, who died 75 years ago on Friday. Zelda’s abiding legacy may be as the wild-eyed, jazz-age socialite once referred to by her husband as “America’s first flapper”, but these delicate paper dolls, so painstakingly crafted out of pleated wallpaper and Belgian lace, offer us a more nuanced and complex image of her.

Too often over the last century, this “wife” and “muse” has become so enmeshed in other people’s narratives – boom-and-bust antics such as frolicking fully clothed in the fountain at the Plaza, for instance – that, at times, her own contributions have been lost. Some may be familiar with her first and only novel, Save Me the Waltz – an auto-fictional account of her metamorphosis from a spirited Southern belle to a woman stymied by social norms – but her vivid short stories, articles and letters are just as significant, if curiously lesser known. And yet, in spite of these achievements, it was only posthumously that some of her stories were finally credited solely with her name.

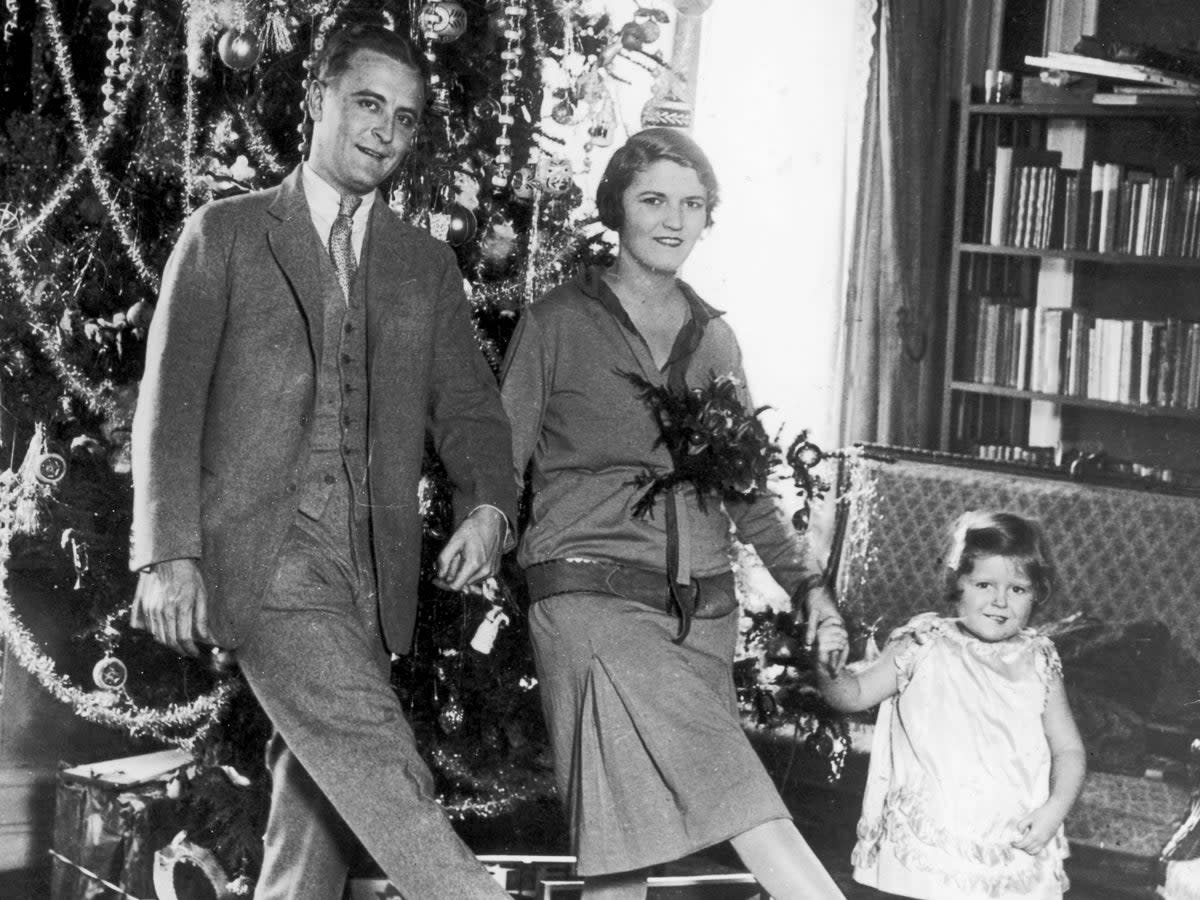

Zelda shuttled in and out of mental institutions for most of her thirties and forties; her quest for autonomy was never a linear one. “I want to live some place that I can be my own self,” Zelda appealed to her husband Scott in 1933. This was three years after she was first admitted to a psychiatric facility on the shores of Lake Geneva, and thirteen years after his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, catapulted the young couple to fame and intermittent fortune during the roaring twenties. Perhaps it is this desire for sovereignty that best encapsulates the bright flashes of creativity that became such a driving force for Zelda over the course of her life.

“I think Scott said, ‘When her flame burns brightest it’s hotter than mine,’” says Judith Mackrell, author of Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation, as we discuss her writing. Like me, Mackrell was drawn to Zelda through her words, so alive on the page, like lavishly painted paper. “Zelda is a shooting star. She blazed so brightly and briefly, there was an extraordinary force of character and talent...” Mackrell tails off. “You hesitate to call it genius because it was so damaged.” In Zelda’s life and work, the relationship between dispossession and reclamation is a powerful one – but a brittle one, too.

It was around the time of her breakdown, in 1930, that Zelda began writing “girl” sketches for an American magazine called College Humor; short stories that displayed an instinctive and original impressionistic style. “The far-away lights from buildings high in the sky burned hazily through the blue,” she writes in “A Millionaire’s Girl”, “like golden objects lost in the deep grass, and the noise of hurrying streets took on that hushed quality of many footfalls in a huge stone square.”

It is the sharpness of her wit, and the strangeness of her prose, that pulls you into Zelda’s sensory world: an inner sanctum that was deeply misunderstood at the time. Zelda was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the autumn of 1930, but posthumous analyses now lean towards bipolar disorder as a more probable explanation for her many fluctuations. “Her mind and her senses were so acute sometimes,” Mackrell muses on her complex psychology, before placing her in proximity to modernist pioneer Virginia Woolf: “That blurring of those lines, between reality and the unconscious, made [Woolf] the extraordinary, receptive writer that she was – and Zelda, too.”

In Flappers, Mackrell makes note of Zelda’s “restlessness”: an agitated quality that ebbs and flows in her stories, too. “The fictions that Zelda began to write were in some ways variations of her own story,” Mackrell writes. “In each she portrayed a different woman whose attempt to fulfil herself was blocked by some essential failure of nerve, or by the constraint of her husband.”

These fictional obstructions become more entangled with real-life biography when one learns of the circumstance in which her stories were originally published. At the time, magazine editors made it a condition that Scott’s name – a more bankable entity – appear on her stories as co-author. In one instance, her name was stricken completely. Zelda’s “A Millionaire’s Girl”, deemed too good for College Humor by Scott’s agent Harold Ober, was sold to The Saturday Evening Post for $4,000 instead of $500, but only if Zelda’s authorship was omitted. “I really felt a little guilty about dropping Zelda’s name from that story,” Ober wrote to Scott at the time – “but I think she understands...”

How to acknowledge this glaring betrayal without turning the rest of their story into a patriarchal caricature? On the one hand, the Great Gatsby author could be both generous with his time and encouraging with his words. Yet on the other, his compassion was often conditioned by the trajectory of his own work. In 1922, Zelda was asked by Scott’s friend, the humorist Burton Rascoe, to write a satirical review of Scott’s latest novel, The Beautiful and Damned, for the New York Tribune. “It seems to me that on one page I recognised a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar,” she teased. “Mr Fitzgerald – I believe that is how he spells his name – seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

It was a sharply funny review that demonstrated the unique qualities of her voice. It was also a tongue-in-cheek jibe at the ways in which that voice could, from time to time, stimulate her husband’s. When Zelda gave birth to their daughter Scottie in 1921, sozzled on anaesthesia, she babbled – to everyone and no one at all: “I hope it’s beautiful and a fool – a beautiful little fool.” All readers of The Great Gatsby will instantly recognise this quote as one of the novel’s defining lines, voiced by the diaphanous Daisy Buchanan.

“He trusted her literary judgement and acted on her criticisms. But Zelda was never his collaborator,” Matthew J Bruccoli, Scott’s biographer, levelled at the “Zelda partisans” in the early 1980s. Which, yes, may be true. But what cannot be denied is the input she gave – and the input that he took. As time went on, Zelda would increasingly wrestle with the ways in which her words fed a narrative she didn’t own.

“I want to write and I am going to write,” she insisted to Scott, just under a year after her autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz, was published in 1932. It was based on the same marital events that Scott drew upon for his own novel, Tender is the Night, which followed two years later. That she managed to write it over a whirlwind period of just six weeks, while she was a hospital patient in Baltimore, speaks volumes to the strength of Zelda’s spirit and the gutsiness of her resolve.

At the time, Zelda’s literary attempt to understand herself, with what Bruccoli would later call her “lavish synaesthesia”, left readers bewildered. Critics swiped at it – and the novel sold poorly. Yet when an edition resurfaced in London in 1953, British reviewers changed their tune significantly. The Times Literary Supplement, for instance, called her prose “powerful and memorable” with “qualities of earthiness and force”.

Tragically, Zelda would never get to read these words. Five years previously, in 1948, a fire had torn through the North Carolina hospital in which she was a patient on the fifth floor. With her death at just 47 came a new wave of critical reappraisal – and, alongside it, a surge of theories that sought to reclaim her alongside so many other misunderstood women of the past. “I think it’s important to separate Zelda from all the gossip, all the urban myth that surrounds her,” Mackrell says of this revisionism. “But also, to separate her from the feminist myth-making, that impulse to cast her as a victim of history and a victim of Scott – I think that denies her an agency of choice.”

Like the paper dolls she made, there is a strength to be found in her fragile hand. Zelda’s autonomy, so fiercely fought for, was always expressed on the page.