‘Waiting for life to start again’: Family agonizes over parental termination

Editor’s note: The story below mentions mental health issues. If you need help or know someone who does, please call 988, the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, available for 24/7, free and confidential support. This is the third piece in a six-installment series about Native American children in South Dakota's foster care system, produced in partnership between the Argus Leader and South Dakota Searchlight.

Home is Christian Banley’s purgatory.

The tan, unassuming clapboard house with a sagging awning and an overgrown front yard sits across the street from Northern State University in Aberdeen and needs a fresh coat of paint.

Inside, the walls were recently painted black and sunlight struggles to make its way through small, curtained windows.

The atmosphere reflects Christian’s pain.

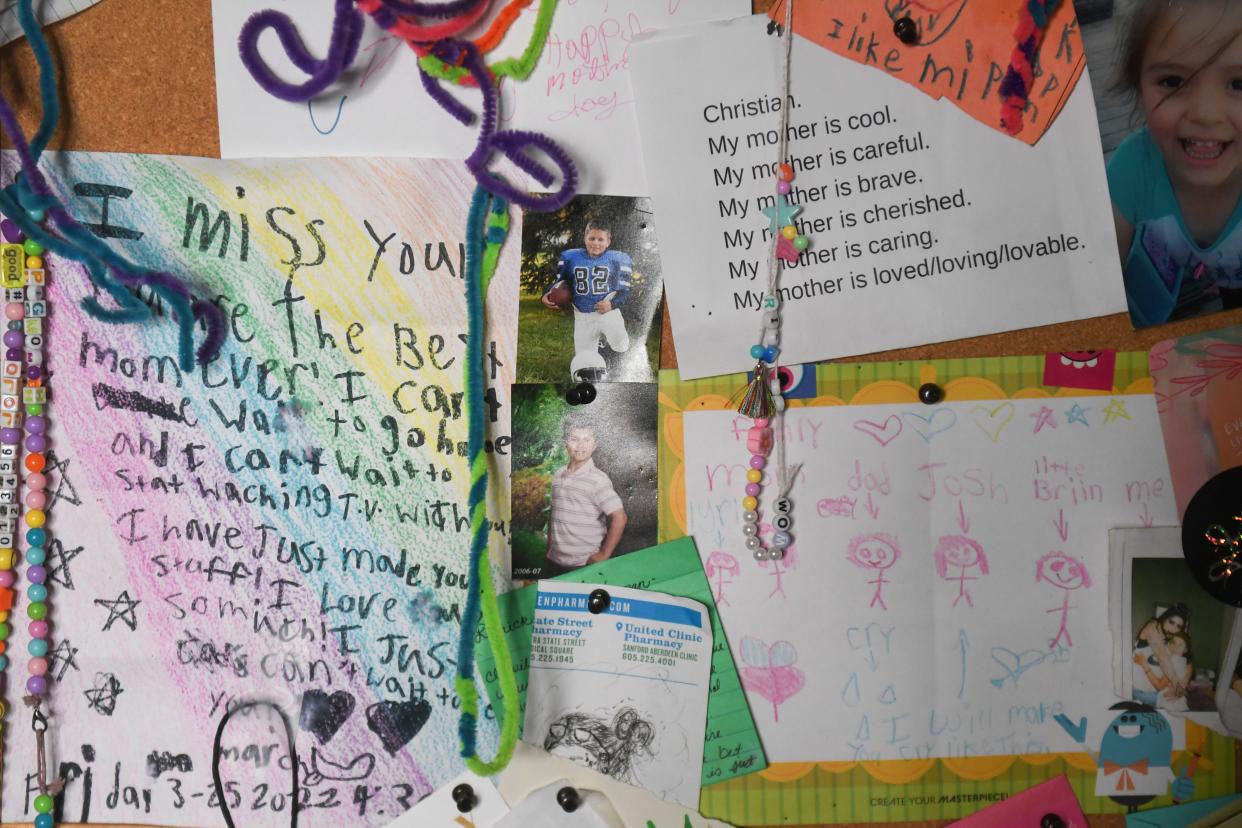

But there is one place that remains brightly lit. A large bay window welcomes the warm afternoon light into Christian’s dining room. The sunlight shines directly on the altar Christian has built for her 9- and 10-year-old daughters.

A favorite Pikachu figurine stands guard over the dining room. Sitting next to the altar is a memorial of loved ones who’ve passed: Christian’s stillborn child, close relatives and friends.

A letter colored with every crayon available and peppered with black-marker stars draws the eye.

“I miss you. You are the best mom ever,” it reads. “I can’t wait to go home.”

But the girls aren’t coming home.

The girls, who are being named only by initials to protect their privacy and well-being, are enrolled members of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe like their mother and 16-year-old brother. The two, L and J, are part of a growing number of children whose parents’ rights have been terminated. Between 2017 and 2021, the number in South Dakota grew by 40%, according to the United States Health and Human Services Department.

Part 1: South Dakota inspired ICWA but still has high rate of Native children in foster care

Those findings are part of an Argus Leader/South Dakota Searchlight investigation examining the issues Native families and children face inside South Dakota’s child welfare system. Native American children accounted for nearly 74% of the foster care system at the end of fiscal year 2023 — despite accounting for only 13% of the state’s overall child population.

Half of the children who enter foster care in South Dakota are reunited with their parents. For Native American children, that drops to 40%.

Christian’s parental rights were terminated in July after a two-year legal process.

The termination is a judge’s signature on a piece of paper, permanently cleaving parents from their child.

They’re not allowed to initiate contact.

They have no idea if their child is up for adoption or if adoptive parents have come to love the child as their own.

The state moves on.

Christian is frozen in place, unwilling to improve her house. While the girls’ return is legally impossible until they turn 18, she waits, hoping they’ll come home.

“We're not going to sand the floors until we know when L and J are coming home, because what if they don't want to stay here?” she said.

Arrest separates family

Before her girls were taken, Christian’s house was filled with friends cooking and eating around the large wooden dining table. Christian tried to provide a judgment-free refuge for recovering addicts and formerly incarcerated people.

The 32-year-old knew what it was like to be judged by those in the small community. She was a pregnant teenager. Christian’s birth mother had been unable to care for her, so she was adopted by her aunt and uncle. She had been in a series of violent relationships. She even ran away as a teen.

By providing a safe place for those in need of a helping hand, Christian wanted to teach her children by example to love people despite their flaws.

“I have a really big soft spot for addicts and prisoners,” Christian said. “I can let them live with me and they can be sober because I'm sober. I’m trying to convince myself that I can save people.”

J and L understood their non-traditional family was recovering from choices made and consequences that followed. They knew why some “uncles” went to prison, and the girls would challenge them to be better versions of themselves, Christian said.

Christian says she didn’t know one of her roommates, living in the locked-off basement of the three-floor house, was using meth and had it in the home.

But on the morning of April 21, 2021, police entered the home with a search warrant.

Meth residue was found on the property and Christian was arrested, according to court documents. Her parents were called to pick up the girls, still at home waiting for homeschooling lessons to start. Their brother Josh, who attended Central High School, was already gone.

Christian was charged with possession of a controlled substance, ingestion and keeping a place for use or sale of a controlled substance, according to court documents. The charges were later dismissed by a Brown County prosecutor.

Then, she was charged with two counts of contributing to the abuse and neglect of a child, triggering a Child Protective Services case.

Journey through the foster system

L, J and Josh moved into a six-bedroom mobile home outside of Aberdeen after Christian was arrested. The place belonged to Thad and Pam Banley, Christian’s adoptive parents and biological uncle and aunt.

The girls struggled to adjust to their new environment for a month, waiting for Christian to come pick them up, Pam recalled.

The 48-hour emergency custody hearing, required by law, was held in June, not in April. The Unified Judicial System could not provide an explanation as to why the emergency hearing was delayed because child abuse and neglect cases are sealed. The hearing happened two days after Thad and Pam had said they couldn’t continue to keep J and L and they couldn’t find other family members to take the girls.

More: Native American families broken up despite federal law meant to keep them together

Thad explained he’d made the call to DSS in June, not because he and Pam didn’t want the girls, but because he wanted the girls to be back with their mother.

“Maybe I was wrong, but I wanted Christian to raise her own kids,” Thad said. “It’s not that we don’t want them, but rightfully they belong to their mother. Whatever the state sees right or wrong, those kids need to be with their mother.”

Thad’s 2021 call to DSS was outlined in a letter sent to the Banleys two years later, notifying them they were not approved to be an adoptive placement for the girls.

While DSS was granted custody of the girls and Josh, they continued to stay with their grandparents during the summer and fall of 2021.

Josh ran away to live with a friend in Nebraska, afraid he would be placed away from his siblings and relatives.

The girls settled into living in the country. Pam recalled the house was filled with quiet conversation and laughter in the evenings while the girls drew at the kitchen table, Pam made supper on the stove and Thad painted birdhouses.

Thad bought palm-sized birdhouses for the girls to paint. The tiny plywood structures reflect the girls' personalities: L’s is simple and orderly, with a purple and pink roof and crisply drawn lines on the side. J used all the colors she could, the house striped in green, orange, pink, blue, white and yellow.

Christian visited the girls once a week in a supervised environment as detailed in her case plan set by DSS and the courts, working toward reunification.

Then Pam suffered a stroke in October 2021. Her son called DSS, asking if L and J could be placed with another foster family nearby as Pam recovered.

But there were no open, long-term foster homes in the Aberdeen area. The girls were able to stay with their youth pastor in an emergency placement in town for a week before being sent together to a foster family in Garretson, 200 miles southeast of Aberdeen.

That didn’t last long. The girls were quickly split: L went to the Children’s Home Society in Sioux Falls while J was sent to a foster family in Madison.

Suddenly, Christian’s 10-minute drive turned into an eight-hour round-trip drive to see her girls weekly. If Christian was late, which she often was because of car trouble or getting pulled over for driving with a revoked license, she would miss the visitation.

She missed seven visits in a 12-month period.

She failed to find steady employment that met the requirements in her case plan, instead relying on her gig work as a cleaner and her OnlyFans account, a paid online platform in the adult entertainment industry. She became isolated from friends and couldn’t find people DSS and the courts approved of to list on a safety plan, the ones who could come check on her children when they returned home and report their findings back to the department.

Months passed. Christian married her boyfriend right after her girls were placed with her parents, thinking he could get custody of them as their step-father. That wasn’t an option, considering his past history of drug use and incarceration.

She subsequently divorced him, thinking it would improve her chances.

More: Memorial for former US Senator James Abourezk set for Sunday in Sioux Falls

“My marriage is over now because of this entire thing,” Christian said. “That was my best friend.”

L and J’s fathers were unable to take custody of the girls since one of them had died and the other was in prison.

Josh eventually returned and was put into Department of Corrections custody in Aberdeen after he’d missed a parole date while he was living in Nebraska with a friend. As soon as he was released, he went back to living with Christian.

He questioned why his mom, who had always provided the essentials — food, water, electricity and wifi — couldn’t get his sisters back. He treasured being a big brother.

Thad and Pam watched as Christian tried to comply with the case plan. Thad, a by-the-book veteran who still keeps his gray hair cut to Army standards, said he grew frustrated as he watched his daughter jump through every hoop put in front of her, without the system caring for her ADHD.

“What it boils down to, for me, is it appears that DSS set her up to fail,” Thad said. “She's not entirely at fault. She did what she could.”

Thad and Pam now live in a quiet home, void of the chatter of two of their grandchildren.

“Yes, it’s sad, and yes, you get upset,” Thad said. “Two, three times a week, I sit and I watch TV here all alone because Pam was in bed early. And I cry those two, three times.”

For Pam, she can’t think about the absence left by her granddaughters.

“I don't want to let the sadness in,” she said.

To stave off the feeling, she picked up a plush toy shaped like a Prozac pill from the living room table and squeezed it. The toy let out a peel of laughter and Pam smiled.

“It sounds like my granddaughter’s laugh.”

Indian Child Welfare Act adds to case complexity

Adding to the emotional turmoil the Banleys face is their allegation that the state failed to comply with the federal 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act. The law is meant to keep Native American families together. When Native children are placed into the foster care system, the law prioritizes keeping the children near their communities and culture.

The Banleys say ICWA applies to L and J’s case since they’re enrolled tribal members. The girls’ case should have been transferred to the Cheyenne River Sioux tribal court, they say, like Christian’s own case when she was a baby.

More: Matson: It all comes down to ‘home’

Christian’s mother left her with Thad and Pam, both Cheyenne River Sioux citizens, and who were granted temporary custody of her when she was 6 weeks old. Thad and Pam adopted Christian, gaining a daughter in addition to their five sons. But Christian’s birth mother still had the right to visit her daughter when she could.

Thad said it was the best case scenario of ICWA working — keeping a Native child with her family. He wants a repeat of that win with his granddaughters. Pam has recovered from her stroke and the grandparents believe they can care for the girls.

“To me when they terminate the parental rights, then those children should be given back to the tribe, period, or given back to us,” Thad said. “It's tribal custom for the children to be raised not only by their parents, but by the grandparents, by aunts and uncles and so on.”

Christian needed a miracle earlier this year. She was a month from having her parental rights terminated and there was no guarantee that Thad and Pam would be eligible to adopt the girls.

Through it all, Christian had been calling the Cheyenne River ICWA office, trying to get someone to look at her girls’ case. An email sent by the state notifying the ICWA director of the case bounced back and Christian said nobody was taking her calls.

In late May, an ICWA caseworker finally called her back.

Frankee Veit had been at the office for less than 100 days. Her case count had grown from 40 when she started up to 57.

“I only had 15 days on that case before they made the decision that it was done. That's probably my most frustrating thing,” Veit said, adding she filled out paperwork for a jurisdiction transfer and that Christian’s brother in Fargo and parents were still viable kinship placement options. “I don't think I had enough time.”

Christian said because of a wrong date on the paperwork, the case was unable to be transferred to tribal court. Christian’s rights were terminated in June.

Miscommunication leads to termination

Thad and Pam were notified via letter from DSS in June that they weren’t eligible to adopt the girls but could continue to have contact with them. It’s a point of contention because the two say the case workers twisted their words.

“They are constantly fabricating information,” Thad said. “They will say a lie just to prove themselves right.”

In response, DSS said that all case records and files relating to child abuse and neglect reports are confidential in accordance with state law, and the department could not comment on the particulars of this case.

“In South Dakota, CPS does not have the authority to remove children from homes and South Dakota courts maintain jurisdiction and oversight throughout the entirety of an abuse and neglect case,” said Emily Richardt, a DSS spokesperson.

In the letter to Thad and Pam, DSS laid out a timeline of moments when the grandparents had expressed they didn’t want custody of the girls, including the June 2021 call Thad had made, and their failure to complete paperwork for a home study and a background check.

More: It takes a village: SD foster program is a new model of care for Indigenous children

Pam disputes what’s in the letter regarding her discussion with the caseworker and her interest in caring for the girls.

“There was no health professional telling me I couldn't keep my girls,” Pam said, as she continued to recover from her stroke. “I was just not ready mentally at the time.”

After expressing her anxiety, Pam said she texted the case worker a week after their discussion and said she could care for the girls and asked to resend the paperwork for the home study. Instead, they got the rejection letter.

The final goodbye

Christian had 15 minutes to say goodbye to L and J at the Children’s Home Society’s visitation room in Sioux Falls.

She held herself together as her daughters cried. She couldn’t cry, she wouldn’t cry. For Christian, this wasn’t the final goodbye.

“I’m not concerned,” she told her daughters. “I know you’re coming home.”

As the minutes wound down, case workers stepped into the room. The girls cried harder and fought to stay in her arms, Christian recalled.

She fell to her knees after the door shut, sobbing.

“It took everything inside of me not to cry with them,” she said.

Her tears continued as she left the Children’s Home Society and went to a nearby park. She contemplated taking her own life.

It was the thought of her son that kept her from walking into the river. Josh became a rock for his mother as she dealt with the fallout of the girls’ removal back in 2021. She was depressed. Josh became more of a parent to Christian than she’d been his mother during that time.

“The only reason that I am not as suicidal as I've been most of my life is because how would it look to him that I was so heartbroken over the girls that I left him?” she said.

Christian says she’s learned her lesson.

She now understands she put her daughters in danger when she allowed her former roommate to live with them and trusted there wouldn’t be drugs in the house.

“I've definitely put them in a very not good environment, but it was not out of malice,” she said. “I was just trying to follow my heart to help and show my kids just how you should treat people. I hate that other people would ruin it for me. But at the same time, I can only blame myself because I knew it could go wrong.”

She also picked up 16 traffic tickets and three serious charges, such as drug possession and shoplifting, in the last two years, according to court documents — a marked increase from her previous interactions with the court system.

She became isolated, depressed and paranoid, saying the child welfare process made her feel crazy.

“How do you defend yourself for two years? That's not who you are and then you become the monster they want,” Christian said.

Each time Thad and Pam enter their bedroom they see the tiny birdhouses the girls decorated. They’re reminded of the two missing grandchildren, their lost birds.

Christian is frozen in time at the Aberdeen house. She hasn’t painted the outside, for fear the girls won’t recognize what it looks like. And she doesn’t want to move, for fear the girls won’t be able to find her again.

The walls of the girls’ bedroom are bare. Stuffed animals, baby blankets and clothes wait in the girls’ closet, their scent fading with each passing day.

Josh wants to move, to escape the prison the two have created for themselves. It’s tormenting, the memory of when the girls were removed wrapping itself around the mother and son, following them throughout the house.

But still they remain.

“We’re both waiting for life to start again,” Christian said.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Parental termination in SD cleaves families from children, leaving pain