Your Vintage Kitchen Tiles Might Have Been Made in a Spark Plug Factory

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Flint, Michigan, is famous as the home of the Buick Motor Company, the oldest extant American automaker. While I knew of its well-reputed art museum—a common feature of Midwestern cities as they became enriched during the industrial booms of the 19th and 20th centuries and sought cultural cachet—it had never struck me as an artistic hub. However, a deep search revealed an intriguing, original, and unique connection between this tile company and the auto industry.

Albert Champion was a wildly successful French-born bicycle and motorcycle racer in the first decade of the 20thcentury, but when he came to the United States to compete, he had trouble sourcing quality parts for his motorbikes. So he decided to import his own from France, creating the first American spark plug company. His endeavor eventually became the Champion Ignition Company of Boston, and then the AC Spark Plug Company due to a nomenclatural dispute with his co-founders. In 1907, the quality of Champion's imported products, along with his racing fame, compelled William Durant, the founder of the vertically integrated General Motors consortium, to contract AC to produce spark plugs for GM's vehicles. Champion moved his business to Flint in 1908 to a new GM-built factory.

All seemed set for success, but there was a misfire. According to historians Margaret Carney and Ken Galvus, authors of the definitive book Flint Faience Tiles: A to Z, during World War I AC's supply of French ceramic insulators was interrupted by German occupation. With the help of engineers at Ohio State University, the plant developed its own ceramic material, one that had a deep domestic supply.

The war, and its manufacturing needs, also ushered in other advances in production. "In Flint, they started using tunnel kilns around 1919," says William Walker, a veteran ceramic engineer who has worked for decades in the spark plug industry. A tunnel kiln is a continuous, domed, 35-foot-long brick oven with the heat source toward the middle. It features a conveyer that shuttles ceramic components through a lengthy warming, firing, and cooling process. This innovation enhanced efficiency. But production didn't always require the large machines' full capacity, and when workers would shut down underutilized kilns to conserve fuel, the heat dissipation cycle caused a structural problem. "As the bricks cool down, they start to crack," Walker says.

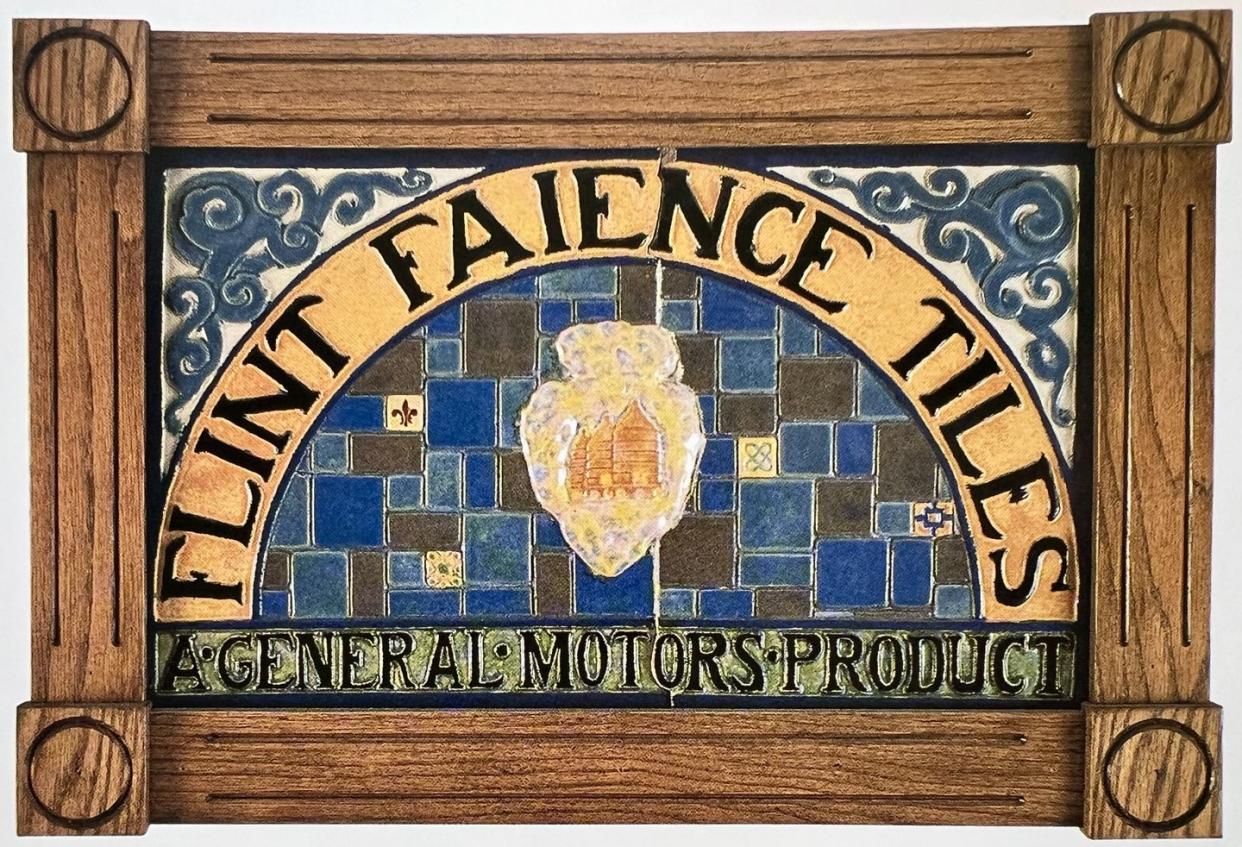

Durant and Champion came up with a novel solution. They decided to find a co-use for the kilns, one that could utilize excess manufacturing capability, allowing the ovens to remain heated and active. The boom in home, industrial, and retail construction that was occurring; the re-emergent Arts and Crafts-era interest in decorative tilework; and an encounter between Champion and Belgian ceramic artist Carl Bergmans all led to a decision to start a tile company. The result, in 1921, was the establishment of an ancillary AC business, the Flint Faience Tile Company.

I first saw the tiles in a real estate listing in the New York Times. They covered the kitchen walls in a 1927 five-bedroom brick house in Detroit's University District, near where my father had grown up, their glazing a murky but alluring range of celadon greens. At first, I assumed they were from the famed Detroit Arts and Crafts–era ceramics studio, Pewabic Pottery. But the article described them as original to the house, and from a company called Flint Faience, which is how I came across the connection between automotive and decorative ceramics.

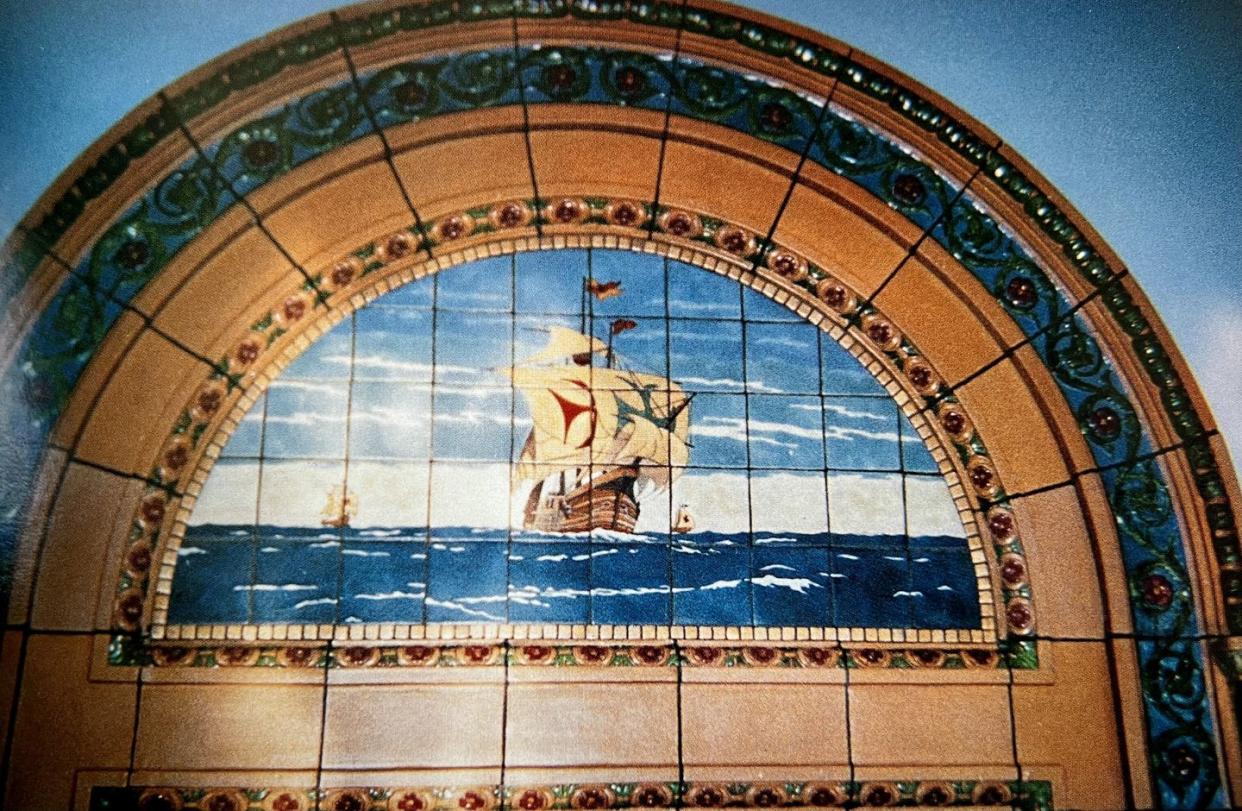

"Their [tile] styles ran the gamut from Arts and Crafts to art deco, with wonderful crystalline glazes and lots of innovations," says Carney, an art historian and founder and director of the International Dinnerware Museum in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as well as co-author of the aforementioned book on the subject of Flint Faience. Some designs depicted objects—religious iconography, characters and settings from fairy tales, buildings, birds, fruit, plants; some were more decorative mosaic-like tessellations; some were large-scale murals; some were solid colors in every conceivable muted hue.

The company claimed in its promotional materials that there were "more than 5000 uses for Faience tile," and that may not be far off. In addition to typical floors and walls, Carney's book documents fireplace surrounds, ashtrays, stair risers, towel rack holders, bookends, tabletops, radiator grilles, and store entrances. It shows images of bizarre Faience-tiled sandbox/drinking fountain/terrarium combos in elementary school classrooms; Faience-tiled swimming pools and decks on ocean liners and in the Rockefellers' New York estate, Kykuit; Faience-tiled bathrooms in the presidential palace in Peru; and tiled stairways in the U.S. Customs house in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Coming full circle, Flint Faience tiles had a special relationship with the auto industry. They were used throughout the Albert Kahn–designed General Motors headquarters building in Detroit from 1920, then heralded as the largest office building in the world. They were also found on the floors and walls of automobile dealer showrooms throughout the country, with period advertisements touting the fact that they were "economical and had easy upkeep, plus their oilproof nature."

And while the ceramic clay used to create the tiles was mainly excavated and transported in from a mine in Zanesville, Ohio, a key ingredient was added on-site during production. "They used ground up spark plug refractories," Walker says, referring to the hardened, heat-resistant ceramic material used to support AC's insulators when they were being fired. "They mixed it with this ground material, grog, that makes the product a bit more robust." Carney notes that "This could have been one of General Motors' earliest recycling projects."

The company had widespread success, with showrooms on Park Avenue in New York and in the Tribune Tower in Chicago, as well as in Detroit, Boston, Cleveland, Atlanta, Saint Louis, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Factory capacity for Flint Faience output was doubled by 1929, according to in-house publication AC Sparks. Despite this, the company only survived 12 years and was closed down in 1933.

Myriad factors may have contributed to its demise. It may have been a victim of diminished building construction in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Depression. Or it may have been slow to adapt to shifting consumer tastes as the Arts and Crafts movement ended in the 1920s. As Carney mentions in her book, it may have been simply a casualty of consolidation at GM, which decided that "the tile business was foreign to the automotive field and it should be dropped."

But the most common reason given was a reverse of the reasons AC had partnered with Bergmans in the first place. GM had great success during the Depression. According to a 2015 article in Michigan History, the company's belt tightening and marketing during the economic downtown yielded increased sales, with the number of GM cars purchased by Americans in 1933 rising by 50 percent over the nadir of 1932. This increased demand meant that factory capacity was better used for vehicular components. "It was always framed in the context that they needed the space back for firing spark plugs," Carney says.

It's a shame that such odd artistic collaborations haven't been more common in the automobile manufacturing in general. They may also be compelling to the spark plug industry in particular very soon, as capacity is likely to diminish again in coming years. I ask Walker if spark plugs have any place in electric vehicles. "We would like to find an application," he says. "But, no."

You Might Also Like