Veteran Music Producer Elliot Scheiner’s Quest to Bring Hi-Fi to Your Headrests

I’m at Clubhouse, a time capsule of a studio in New York’s Hudson Valley where artists from the National and the Lumineers to Linda Ronstadt have recorded music. My vintage-rock brain is duly blown: In one corner sits the Fender Rhodes electric piano that accompanied Elvis Presley’s original Vegas run, “LV Hilton” stenciled on its surface. In another, a 1902 concert upright left here by songwriter Ben Folds.

This story originally appeared in Volume 15 of Road & Track.

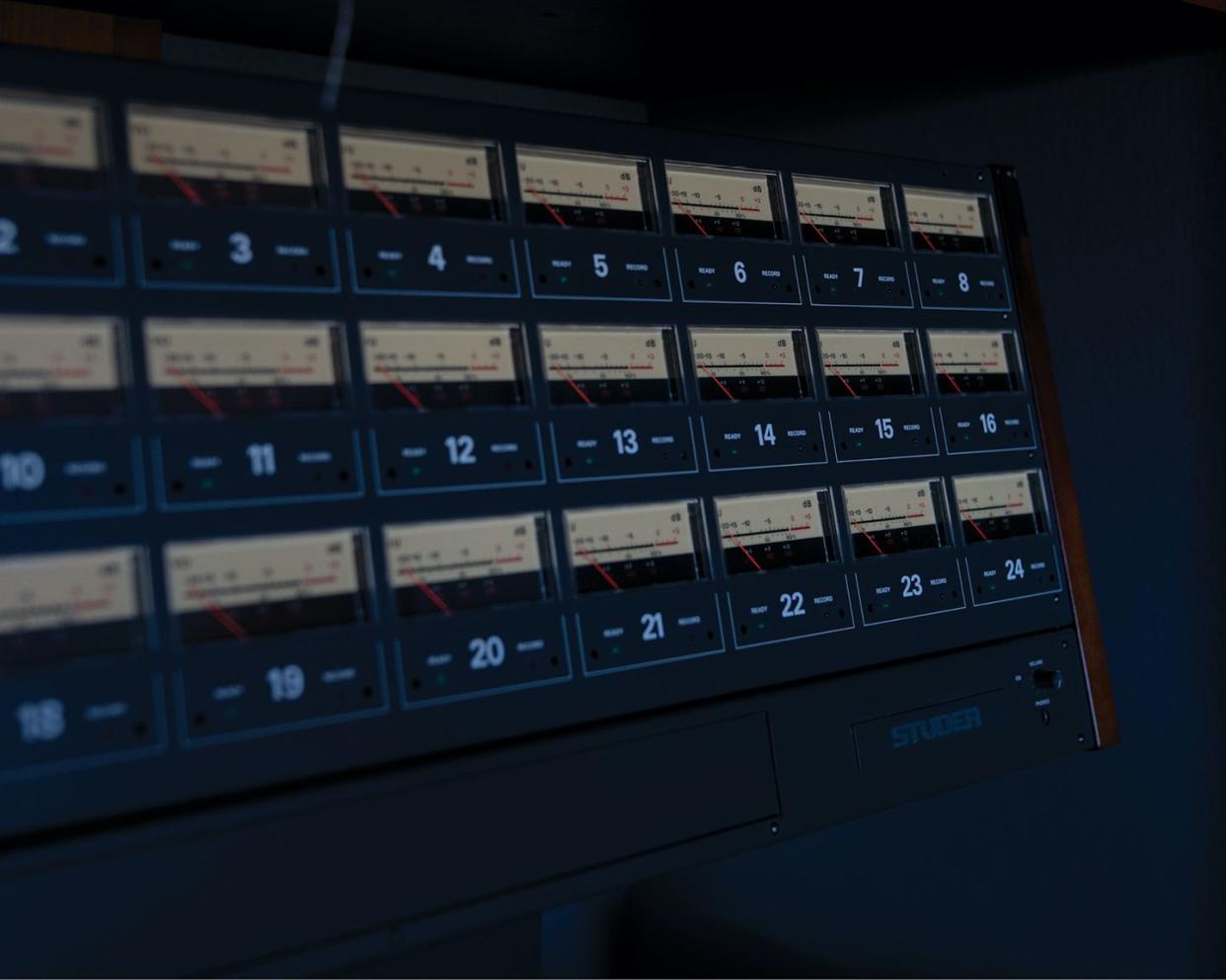

It gets better. Fronting a prized 28-channel Neve console—the solid-state recording desk that defined Seventies rock, with a late encore for Nirvana’s Nevermind—is Elliot Scheiner, the eight-time Grammy-winning producer, mixer, and engineer.

Perennially dissatisfied by the tin-can state of car audio, Scheiner lobbied initially skeptical automakers to raise their game. Scheiner tuned the industry’s first factory DVD-Audio 5.1 surround-sound system, the Panasonic ELS unit in the 2004 Acura TL, equipped with a now-quaint eight speakers and 225 watts.

Scheiner, 75, has driven up from Connecticut this morning in his Aughts-era Ford Thunderbird as he prepares to record an album with jazz singer Madeleine Peyroux. An Acura MDX Type S Advance is parked outside, its 1000-watt, 25-speaker, 22-channel ELS Studio 3D Signature Edition system the latest beneficiary of Scheiner’s golden ear.

It’s an ear that leaned close to tweak Van Morrison’s guitar sound on “Moondance.” In fact, Scheiner has guided music from Fleetwood Mac, Aerosmith, the Eagles, Queen, Sting, Foo Fighters, and Beck. He helped birth notoriously meticulous Steely Dan albums—some requiring more than a year of Kubrickian takes with a revolving army of session musicians—which became the benchmark for a generation of studio engineers.

So when Scheiner bids me into his sweet spot at the Clubhouse desk to hear music as God, Bach, or the Beatles intended, he becomes an ideal guide for today’s musical quest: how to re-create studio magic in your car as faithfully as possible. That’s been Scheiner’s personal earworm since the Eighties, including at Los Angeles’s fabled A&M Studios.

“When we finished a mix, they could broadcast it from one room to a ’57 Bel Air convertible,” Scheiner recalls. “And you’d go in the car and just listen, basically to hear how bad it was. In all the cars, it just never sounded good enough.”

Roll tape to 2005, when the Acura system tuned by Scheiner was more than good enough. After Scheiner engineered the Foo Fighters’ In Your Honor, Dave Grohl and his bandmates heard and approved a final 5.1 mix not in the studio but inside the car. Finally, Scheiner and the artists whose vision he serves—plus the cars’ owners who were singing along—could listen on systems that hit the right notes.

A Brief History of Rhyme

Whistlin’ Dixie aside, the first music heard in cars emanated from crudely repurposed home radios. In 1930, Paul Galvin stuffed a prototype AM radio into his Studebaker in time for a broadcasters’ convention, branded it “Motorola,” and became a millionaire. Blaupunkt brought the first FM car radio in 1952. CBS Laboratories’ and Chrysler’s Highway Hi-Fi records skipped into oblivion in 1959, despite clever tech that packed 45 minutes of music onto a seven-inch record. Eight-tracks, cassettes, and CDs have all given way to apps, streaming, and satellite radio, bringing variety at the price of (mostly) compressed audio files with sound quality worse than that of a CD.

Yet we’re now arguably entering a golden age of car audio, driven by new tech and familiar luxury one-upmanship. Names once familiar only to audiophiles—Bang & Olufsen, Bowers & Wilkins, Burmester, Meridian, Naim, Mark Levinson, Lexicon, Infinity—are proliferating on our roads. Akin to a horsepower race, luxury cars can now pack more than 1000 watts and two dozen speakers, with nearly a separate amplifier channel for each.

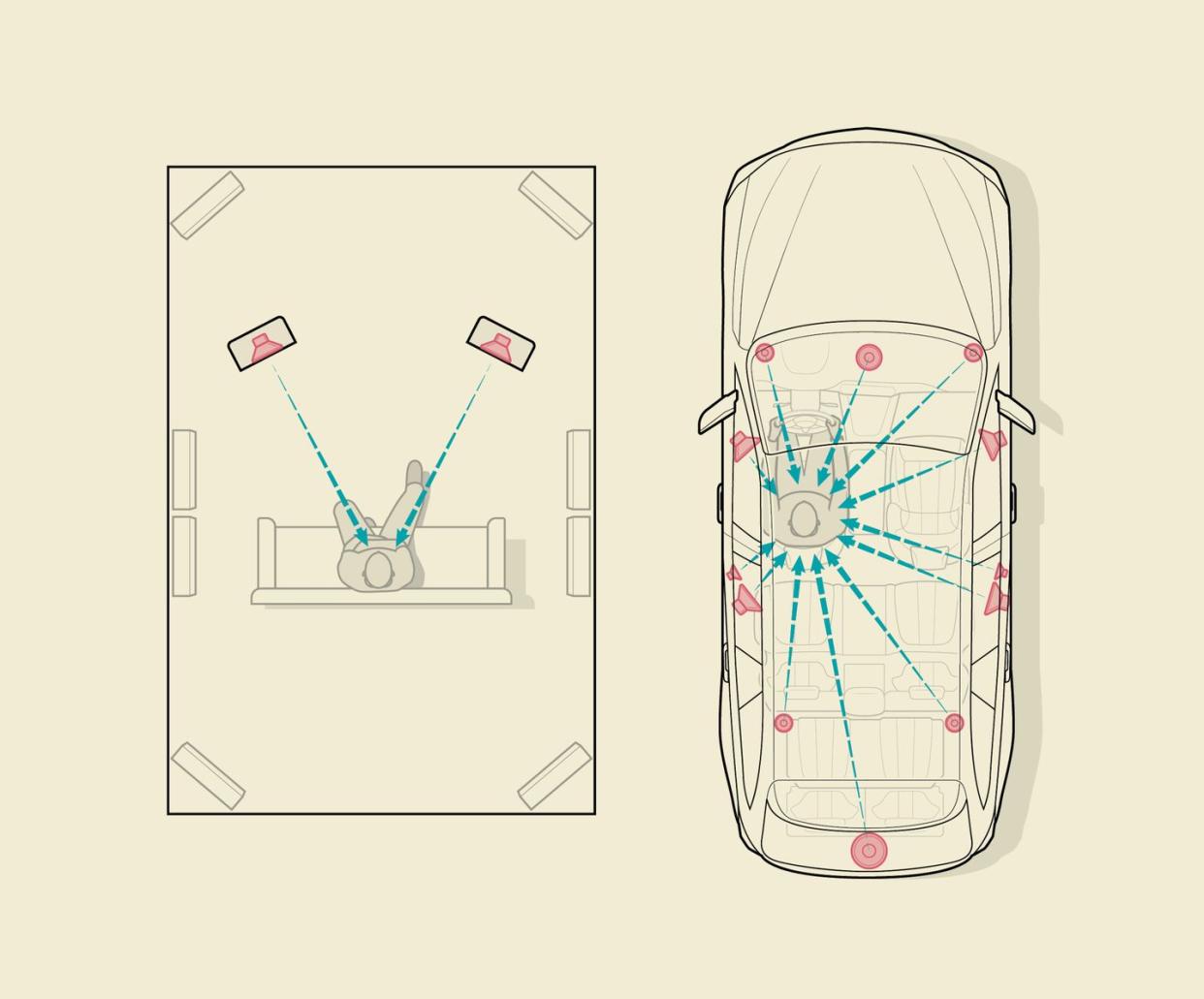

Yet familiar challenges remain. From cramped quarters to hard and asymmetrical surfaces, car cabins are a sonic minefield. Occupants are jammed up against doors rather than seated at the idyllic center of the speakers’ soundstage.

“Vehicles were always considered one of the worst audio environments,” says Rishi Daftuar, who leads system design for Lexus’s Mark Levinson systems as Harman International’s senior principal acoustic systems engineer. That’s been changing, Daftuar says, with top audio systems delivering sweeter playback than your average home setup. How many people have a dozen speakers in their living room, with equipment modeled, tuned, and optimized for their space and fixed listener positions? It’s rather unlike most of us, who haphazardly prop a Bluetooth speaker behind a potted plant in our living room.

Audio systems must boost certain bass frequencies by about 10 dB to counteract road and engine noise. But they can also use cabin gain—the phenomenon wherein smaller spaces cause bass pressure to build quicker than larger spaces do—to amplify bass passively, for the chesty thump you usually experience only at concerts. Critical time delays ensure music from multiple speakers arrives at ears exactly when it’s supposed to.

In Harman surveys, people cite their car as their most enjoyable and frequent listening environment. A Seventies teenager fishing under the seat for an Exile on Main Street tape might have said the same, but if that teenager heard the Stones’ “Loving Cup” pour from the speakers of a modern luxury SUV, he’d start measuring space or a water bed.

“There’s an emotional connection between driving and listening to music that transcends generations,” says Jonathan Pierce, director of global experiential R&D at Harman Automotive.

As for today’s digital tracks, which often stream from apps like Spotify or Pandora in mediocre quality—what Pierce calls “the bane of my existence”—many experts predict that the audio-quality problem will solve itself in our new big-bandwidth age. From Tidal’s high-fidelity streaming to Spotify Premium at 320-kbps quality, Pierce sees lossless or CD-quality music as an inevitable advance for in-car listening.

Senses Working Overtime

It’s not all about the ears. The visual design of speakers was once largely automakers’ domain, but audio companies are developing signature looks too. Automakers let audio partners advertise their brand names on shiny speaker grills.

“In any industrial design, the first interaction is with your eyes,” Pierce says. “And if you’re paying high dollar, visual aesthetics can be equally important.” As long as there’s no bait-and-switch in sound, he adds. “A system can look beautiful and ornate, but if sound quality falls flat, you’re disappointed as a consumer.”

Audio designers face a familiar hurdle in customers or suppliers who prefer pinching pennies to tapping toes. Mark Ziemba, Panasonic Automotive audio systems manager and Scheiner’s tuning partner for about 20 years, puts it more symphonically. “You can do great things with digital tech, but you can’t make a Stradivarius out of plywood,” he says. “Core acoustic tech has suffered because they’re commoditizing speakers, and that’s sad.” What surrounds speakers is also critical to ultimate sound quality. Speaker grills should be as audibly transparent as possible to avoid muffling sound but still robust enough to offer protection from children’s sticky fingers. The steel enclosures wherein most car speakers reside are a notorious hotbed of unwanted noise and motion.

“An amp can put out a signal and stop, but a speaker is like a vibrating spring,” Ziemba says.

On several Acuras, Panasonic’s Acoustic Motion Control sends a corrective signal to the amplifier to stop the speaker faster. Designers caution that speaker count alone isn’t a be-all and end-all, but they’re putting woofers, coaxials, and tweeters anywhere they can to create accurate, enveloping 3-D sound, including headliners, roof pillars, headrests, or center consoles.

To that end, better materials help. Ziemba cites the MDX Type S Advance’s 1.7-inch carbon-graphite dome tweeters. Sure enough, they faithfully reproduce tricky frequencies that can be strident and ear-fatiguing on lesser systems—say, Bob Dylan’s acoustic guitar and harmonica on 1962’s “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down.”

“Those frequencies can be torture for a tweeter,” Ziemba says. “Now it sounds like Dylan is in the car with you; there’s a sweetness to the sound that’s unusual in a car.”

In testing and validating onboard systems, six-microphone arrays are placed and angled at a listener’s approximate head position, while laptops and sound cards generate pink-noise test frequencies. HATS, or head-and-torso simulators resembling crash test dummies, have microphones in their ears, as well as mouth speakers to fine-tune hands-free communications. For all of that, Ziemba says, a tiny adjustment in volume or equalization can improve playback in a way no objective tool can measure. “It still takes a human listening to make that final determination,” he says.

In the Eighties, Ziemba and a partner created Listening Test Technology (LTT). Adopted by several OEMs, LTT taught hundreds of students how to listen to music and grade audio quality. In addition to its experts, Harman recruits laypeople to listen to and score seven set tracks, chosen in part for challenges they pose to systems, on various criteria. (Since times and listeners change, Harman recently replaced Steely Dan’s “Cousin Dupree” with Daft Punk’s “Fragments of Time,” a different genre but a song with similar vibrancy and active rhythm sections.)

Naturally, Panasonic and Acura see Scheiner as their tuning trump card. Akin to Albert Biermann, the now-retired chassis guru who took BMW’s M cars to ineffable heights, Scheiner melds his deep institutional knowledge to impeccable craftsmanship, then sprinkles on some black magic.

“It’s not just a cut-and-dried academic thing,” Ziemba says. He cites Scheiner’s mixes of classic R.E.M. albums, the nuances he coaxed from Michael Stipe’s heartfelt vocals. “Elliot knows not just where the instruments are supposed to be, what phrases were played, but the mood the musicians were in. Whatever emotion the artist was feeling, he wants to bring that into the mix.”

It wasn’t always so, Scheiner is quick to add. He began his career as an assistant to legendary engineer and producer Phil Ramone in 1967.

“Back then, I based everything on Sgt. Pepper’s and being high,” Scheiner says with a twinkle. “But Phil taught me what I should be hearing.”

Hearing Is Believing

After listening to tracks in the sonic temple of Clubhouse, Scheiner, studio owner Paul Antonell, and I hop in the Acura for a drive. Scheiner rides shotgun as dream DJ, including running commentary and fly-on-the-wall rock stories. (Steely Dan’s “Hey Nineteen,” we learn, was inspired by Scheiner.)

The MDX Type S Advance’s top-tier ELS unit would floor any music lover, especially with 5.1 mixes suffusing the cabin in six-channel bliss—not typical “surround sound” signal processing, with bogus “concert halls” and other artificially sweetened room effects. Among the clues to greatness in the MDX: Music sounds as pure and crystalline in the back seats as it does up front, partly due to center-console speakers and authentic three-way sound (woofer, coaxial, and tweeter) for all occupants. We can also hold a normal conversation, even with music cranking. It’s a startlingly good system, particularly considering it’s in an attainable daily-driver SUV and not some rolling Xanadu.

I pull up my own songs and artists, playing Sault, the shapeshifting R&B-funk-Afrobeat collective, and the ear-tickling siren Santigold. Then, in a hat tip to Scheiner, I cue up R.E.M.’s “The One I Love,” Peter Buck’s Rickenbacker 325 chiming that foreboding riff in stadium-rock splendor. It’s a transformative upgrade from my mediocre home Sonos system. I’m starting to feel guilty about just hanging out. If we were teenagers, the cops would pull up any second. Antonell chimes in from the back, seemingly reading my thoughts.

“I can’t remember the last time I just sat in a car listening to music,” the studio owner says. “But I discovered music like this. It’s how I became a fan.”

Scheiner listens intently, calling attention to a bass attack here, a musical filigree there, the space between notes like a held breath.

“I always strived to make music where you can hear every detail if you focus,” Scheiner says. “And that’s the goal: to have everything sound exactly like it did in the studio.”

You Might Also Like