‘A very long shadow.’ Thousands in Eastern WA still live in homes with racist covenants

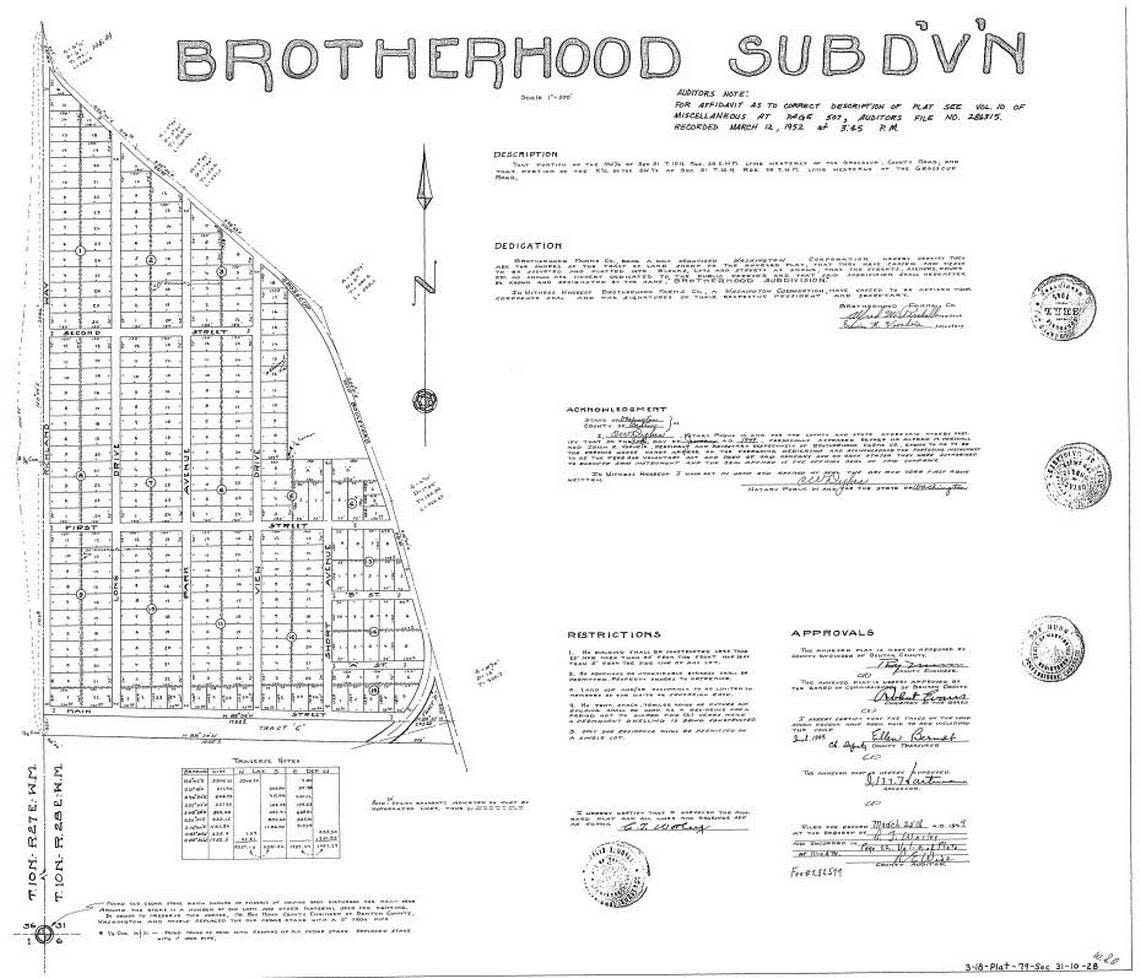

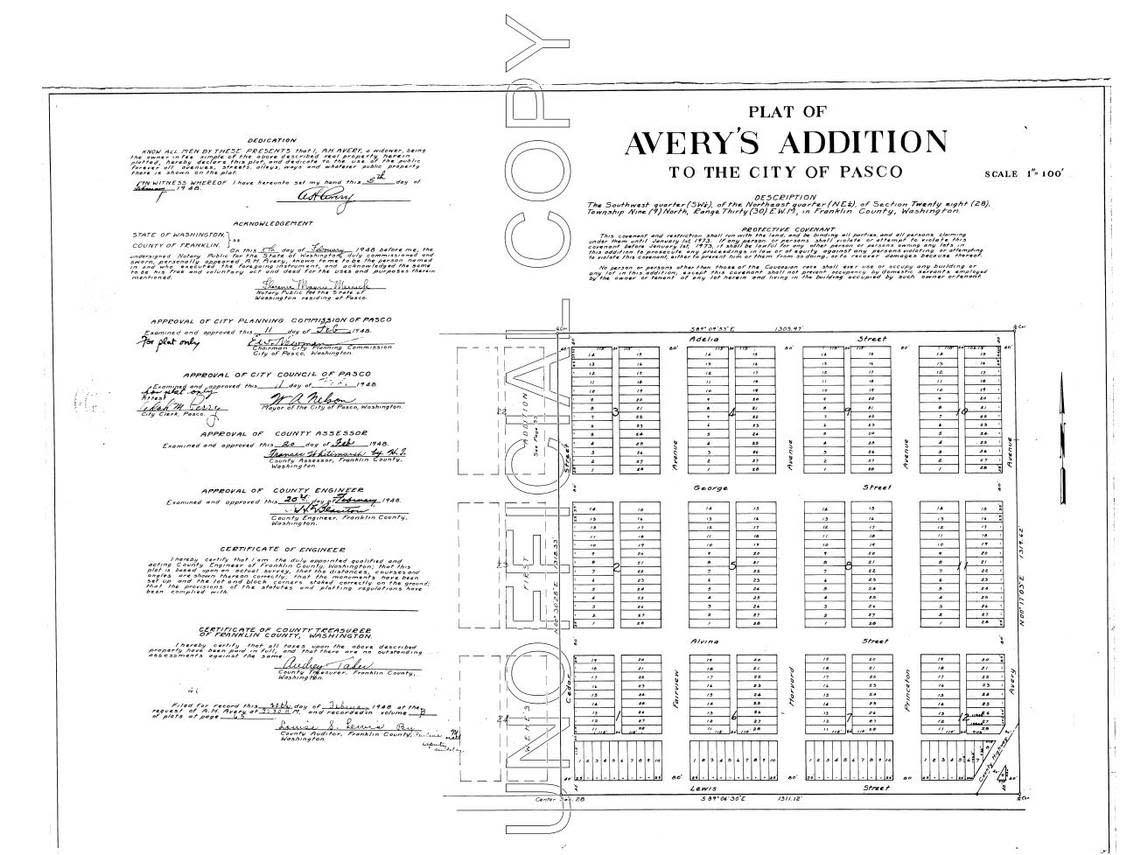

“No person or persons other than those of the Caucasian race shall ever use or occupy any building or any lot in this subdivision...”

These are racially restrictive covenants. And they’re a product of 20th century housing discrimination — an attempt to segregate and bar people of color from owning property in certain neighborhoods.

A Washington state initiative so far has found more than 1,400 properties in Benton and Franklin counties with this unconstitutional language.

Most are in Kennewick — and researchers are still finding more cases.

“Basically, a covenant is a legal agreement that attaches to a property and it restricts what the buyer may or may not do. And it continues on with the property,” said Larry Cebula, a history professor at Eastern Washington University.

“It’s not just for a given sale. It’s attached to the property in more or less a permanent way,” he said.

Cebula and a team of researchers are leading a project funded by the Legislature to identify and list every racial covenant in all 20 Eastern Washington counties.

A similar team at the University of Washington is focusing on counties west of the Cascades.

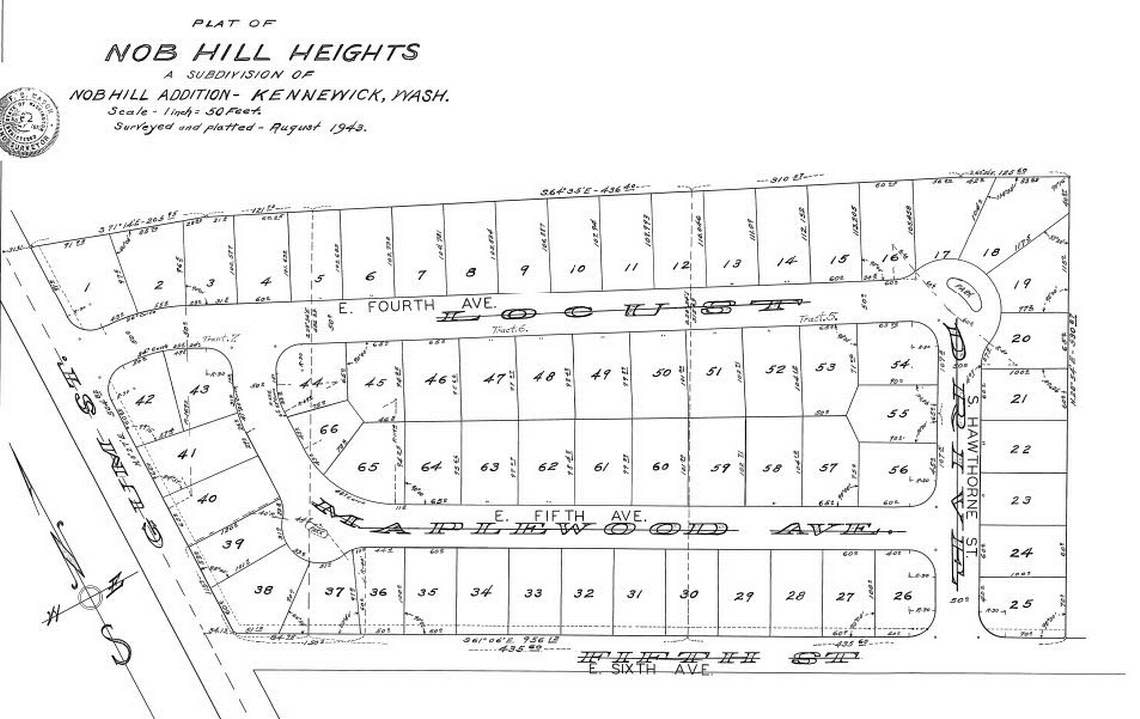

The team is scrounging plat maps, deeds and any other publicly available property records to find the offending covenants. To date, the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project has identified more than 50,000 properties across the state.

Washington is the first state in the U.S. to attempt the effort.

And Cebula says the Tri-Cities is the most interesting place in Eastern Washington to research covenants — mostly because of the“stark differences” between the three main cities in the 1950s and 1960s.

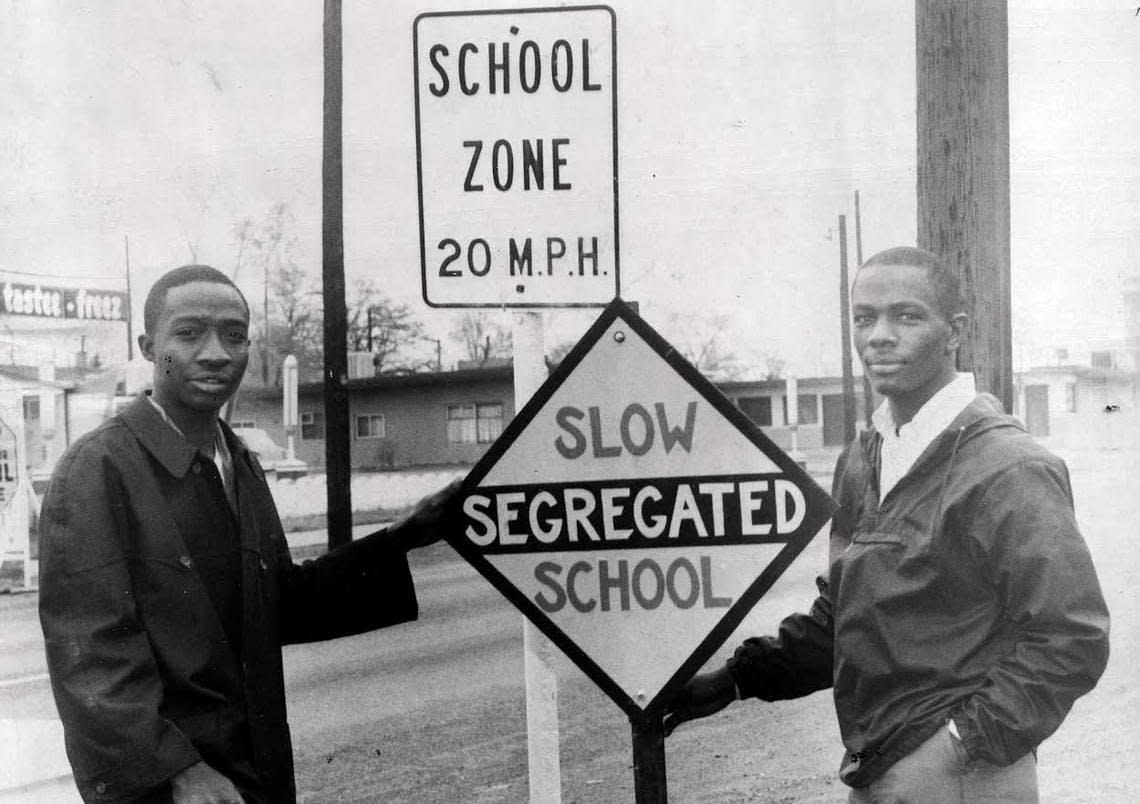

‘Birmingham of Washington’

Kennewick was a known sundown town, deemed the “Birmingham of Washington” by a former northwest branch president of the NAACP, according to an article by WSU Tri-Cities history professor Robert Bauman.

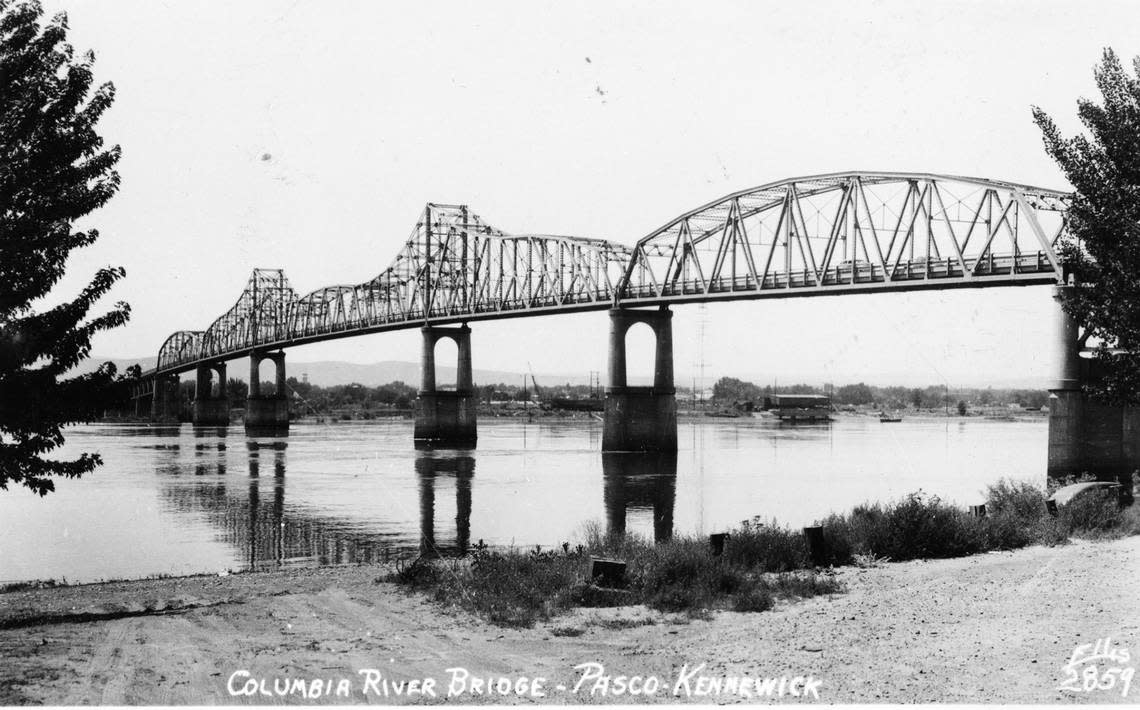

Across the river, in east Pasco, was where nearly all of the Tri-Cities’ Black residents lived. Covenants further separated Black families from whites along the old railroad tracks.

“The unique racial history there where you have Chinese going way back, Japanese more in your area, you have some African Americans, you have Native Americans in your area — and then you have the arrival of a substantial number of Blacks during the Manhattan Project,” Cebula told the Tri-City Herald.

The Racial Restrictive Covenants Project was originally created and funded by House Bill 1335, signed in 2021.

And researchers, professors and supporters are lobbying the Washington Legislature this session for additional funding.

With two more years of funding, the researchers plan to continue to digitize records, fund research efforts to review paper plats and deeds, continue to build a county-by-county database and a GIS map, and work to help homeowners to remove racist covenants.

An infusion of $475,000 to EWU would help them complete the project and place these covenants on a county-by-county map.

Tri-City racial covenants

Racial covenants in the Tri-Cities affected seasonal agricultural workers, Jews, Asians and immigrating Black families coming to the area to work at Hanford.

They’re found on properties in the Glenn Memorial Park neighborhood in West Richland, the old downtown Hotel Pasco property, Nob Hill in east Kennewick and homes south of Hatfield Park in Kennewick — and there’s likely hundreds or perhaps thousands more yet to be uncovered.

In Benton County, a review yielded 14 different plat maps with racial covenants that affected 1,013 properties. Just four racial covenants were found in Franklin County on 338 properties.

The covenants may not be enforceable today, but Cebula argues they shaped home ownership and the neighborhoods we live in today in substantial ways.

“There’s a very long shadow with these things,” he said. “It’s worth investing in because these things are still on the books. Thousands of people in Eastern Washington live in homes that still have covenants on the property title and chain property records. We’re giving them information and the ability to remove it. We’re empowering homeowners.”

The group started by reviewing digitized plat maps — these are surveyed diagrams used to show geographic divisions between properties in neighborhoods, cities and counties.

A planned hand-by-hand microfilm search of undigitized plat maps and deeds for the two counties between the 1920s and 1960s at the Secretary of State archives in Ellensburg will likely produce many more documents.

Tara Kelly, director of research for the Racial Restrictive Covenants Project at EWU, estimates they could find at least 60 more plat maps in Benton County alone affected with racial covenants.

“We could find 100, we could find 50. It’s really surprising. It’s not predictable,” she said.

“I don’t know if there are going to be a lot, but there are going to be some,” said Benton County Auditor Brenda Chilton, whose office records property.

“It’s a hugely important project. It’s something they’ve talked about for years, and we’ve tried to be very cooperative with them.”

Across all 20 counties in Eastern Washington, 561 racial covenants have been identified so far affecting more than 7,300 properties. More than half those properties are in Spokane County.

In the Puget Sound region, UW researchers have identified far more properties — more than 40,000 — affected by racially restrictive covenants across five counties. There are still five other counties on the west side yet to be scrutinized.

“I think hardly any homeowners who own a home covered by racial restriction know about it. I can almost guarantee you 95% have no idea, because who has looked at their plat map?” Cebula said.

Shelley v. Kraemer

In 1948, a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, found that racially restrictive covenants in property deeds violated the equal protections provision of the 14th Amendment and were unenforceable.

Cebula says developers kept writing racial covenants well into the 1960s since putting them in property records still wasn’t illegal. The 1968 Fair Housing Act changed that.

“We are finding most of ours in Eastern Washington in the 1940s,” Cebula said.

The covenants paired with redlining and other discriminatory housing practices stymied generational wealth for generations of Black Americans, researchers say.

Today, white families (about 67%) in Washington are twice as likely to own a home as Black families (32%), said UW professor James Gregory during a recent legislative presentation to the House Local Government Committee.

A large part of this is because housing prices had boomed by the time desegregation efforts commenced in the 1980s, effectively shutting families of color out of the housing market.

U.S. Census data reflects that.

‘Unspoken division’

In the 1970s, about 62% of all Black residents in Benton and Franklin counties still lived in east Pasco. Today, Black Tri-Citians live all over the region.

There currently exists a process for modifying property records with restrictive covenants to strike the language, but some counties are unaware of it because they’ve never had to use it.

Chilton said no one has ever come into the Benton County Auditor’s Office requesting a modification. If they did, she’s not sure what they would do.

But as word gets out about this project, she expects to see more people coming in.

“There’s a lot of families in the Tri-Cities that have been here for a long time,” she said.

Including Chilton’s.

Her grandparents grew up in a pink house along Bonneville Street in Pasco. Growing up in the Tri-Cities, there was still an “unspoken division” even after passage of the Civil Rights Act.

“My Black friends lived on the eastside, which is the east side of Oregon Avenue and my white friends lived on the west side. You don’t see that anymore, which is heartening,” she said.

“This is an important project to me… I know the struggles even back then, so to get the opportunity to do this work is important.”