Vanderbilt University aims for excellence in divided times — throughout 150-year history

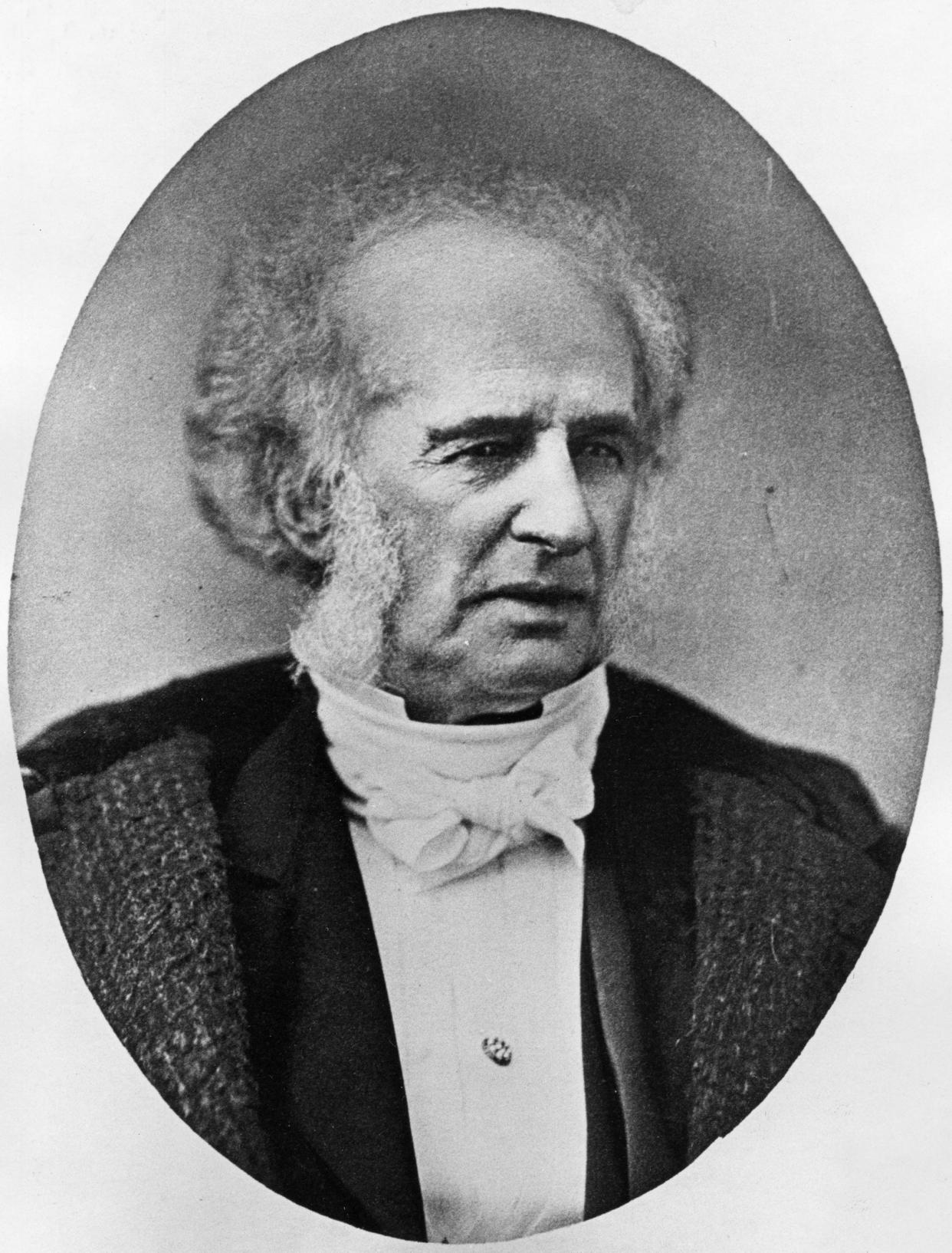

It all started with $1 million, a deeply divided nation and the vision of a man named Cornelius Vanderbilt some 150 years ago.

A railroad and shipping magnate, Vanderbilt sent a $1 million endowment with a handwritten letter to Bishop Holland McTyeire in 1873 to help establish a university in Nashville. The Civil War had ended just a handful of years earlier. In his letter, Vanderbilt charged the school to “contribute to strengthening the ties which should exist between all sections of our common country.”

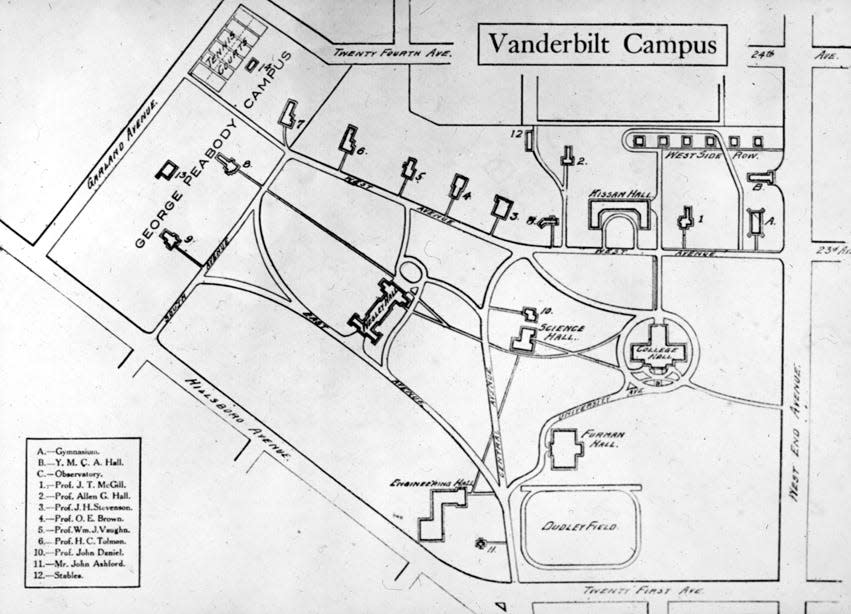

The school was briefly called the Central University of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, before changing its named to Vanderbilt University ahead of its opening. In the fall of 1875, the first 307 students arrived on campus.

This March, the university kicked off a celebration for its 150th anniversary, also known as a sesquicentennial. The school has become a leader in research, academics and social causes over the years.

In 1914, the school parted ways with the church and struck out on its own. In the 25 years that followed, the university weathered World War I, the Spanish flu pandemic and the Great Depression. After World War II ended in 1945, the passage of the G.I. Bill bolstered the university’s enrollment. The university, along with the nation's economy, was booming.

Vanderbilt’s first Black student, Joseph A. Johnson, was admitted in 1952 to the Divinity School, but segregation and Jim Crow laws persisted into the 1960s, spurring the Civil Rights Movement.

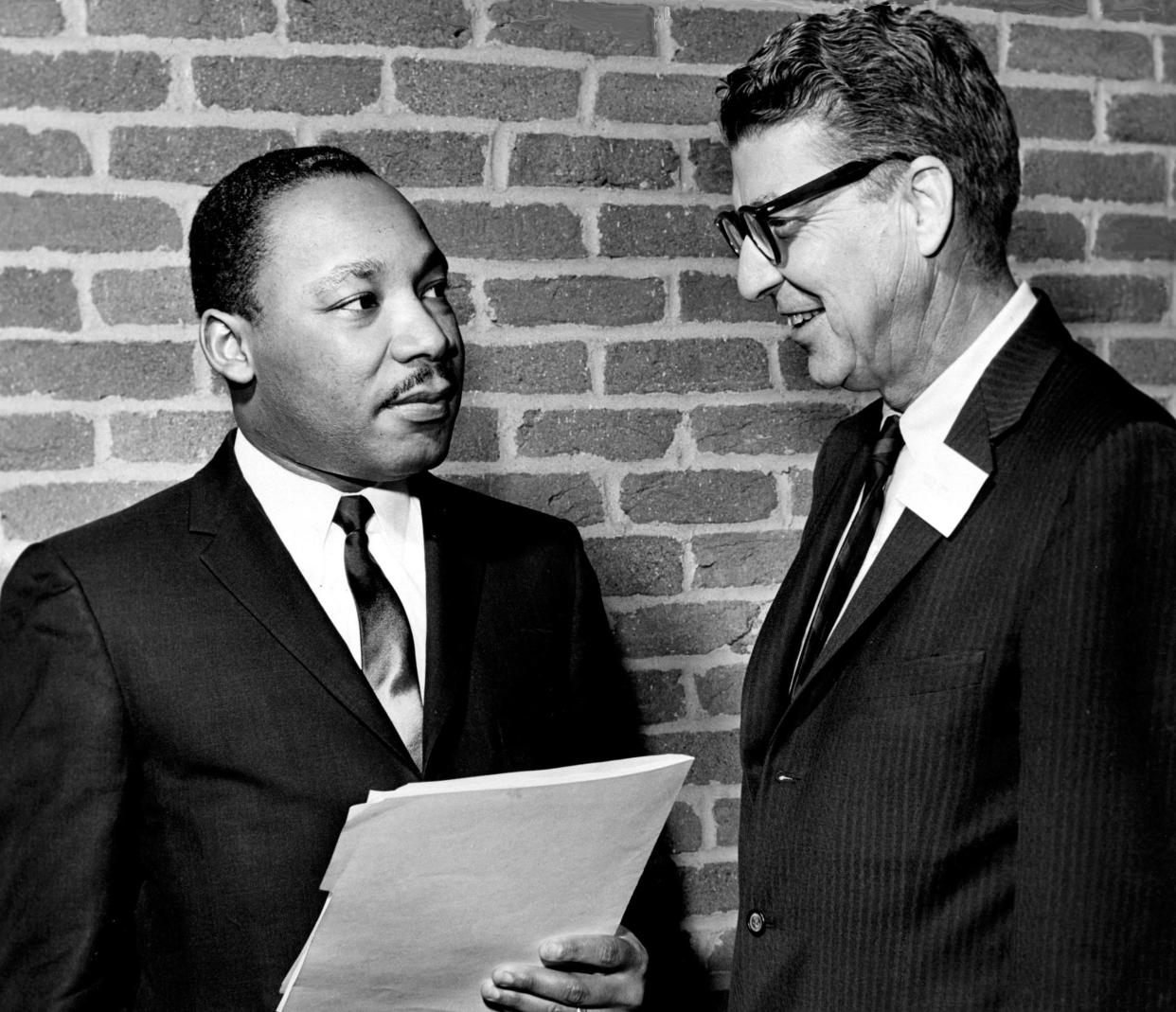

Drawing on its founding principles of bringing people together and fostering civil discourse, the university hosted a wide array of speakers as part of an ongoing symposium. It brought voices from opposite ends of the spectrum, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Strom Thurmond, who was a vocal supporter of segregation. The move sparked intense controversy and calls for leadership to resign. But the university remained committed to its cause, said Daniel Diermeier, the school's ninth and current chancellor.

“It focused on an exchange of ideas rather than shouting at each other,” Diermeier said. “That is the Vanderbilt way.”

Diermeier recalled that story, among others, as he reflected on the university's 150th anniversary. The extensive sesquicentennial project includes meticulously curated historical exhibits, a website, a series of videos, photos, events and a special print magazine.

Diermeier believes that core, founding value of civil discourse — among many others — holds strong today despite heightened polarization and a rapidly shifting academic landscape.

Granted, Vanderbilt has not always gotten things right, which is something Diermeier readily admitted in an interview in early November.

For example, he said, the university expelled James Lawson, a Black student in the divinity school at the time, for his role in the 1960 lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville. The sit-ins were a form of protest against segregation that the late Rep. John Lewis also participated in.

The university later faced a "reckoning" with that period in history, Diermeier said.

Lawson went on to become a reverend and an iconic Civil Rights leader, along with Lewis. In 2022, under Diermeier's leadership, the university launched the James Lawson Institute, which focuses on studying nonviolent movements.

“I think that’s an important part of Vanderbilt — to look at things that were difficult, that were not perfect, that … were broken and have the courage to heal," he said. "There’s a story of redemption here that I find very powerful. That shows you the positive power that a university can have.”

While Vanderbilt's social role in the Nashville community and beyond is a touchstone for the university, its thriving academics, drive for research and recent breakthroughs also show its evolution over the last 150 years.

A visual representation of that evolution can be found by wandering its sprawling campus, nestled between 21st Avenue South and West End Avenue in Midtown Nashville.

A walk across campus

Regardless of where you first set foot on campus, you’re likely to see the towering Kirkland Hall jutting up from the landscape. If you head east, weave between the Bishops Common and the Vanderbilt Law School building, and walk up Grand Avenue, you’ll find Diermeier's office overlooking the northeastern corner of campus.

He said he likes to take walks on the idyllic campus, which was designated as an arboretum in 1879, to clear his head. He often strikes up conversations with people or stops for selfies with students as he goes.

That friendly and collegial spirit carries over as you head a few minutes down 21st Avenue South, where you’ll find the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries — and university archivist Kathy Smith hard at work.

She’s spent the greater part of the last 30 years patiently curating, updating and preserving the university's archives. She could talk for hours about Vanderbilt history. Even so, she quipped, she imagines she only knows about 1% of the university's story.

"Maybe 2% if it's from the last 50 years," she said with a smile.

For the 150th anniversary project, Smith tracked down a massive variety of materials to display. Aside from the anniversary project, her daily duties include helping students, faculty, staff and the general public find what they need in the university’s vast library and archives. She often thinks about what the founders would say if they could see the university today.

"They couldn't have imagined what it has turned into now, 150 years later," Smith said. "It is beyond their wildest dreams."

Cut across the library lawn to the Saratt Student Center, head down to the basement and you’ll find offices for the Vanderbilt Hustler, the student newspaper. Senior Rachael Perrotta is editor in chief.

That same concept of collaboration and support shined through as Perrotta, a triple major in cognitive studies, political science, and communication of science and technology, recounted her final year on campus so far.

Perrotta recalled hearing sirens blaring past the Vanderbilt campus as they raced to the Covenant School just a few miles away on March 27. A shooter left three children and three staff members dead that tragic day. In the days and weeks that followed, Perrotta and her team leaned on each other heavily as they covered the fallout of the shooting.

Perrotta was adamant about getting her team outside as they faced the harrowing task of covering a school shooting in their own community. She said they'd sit in groups of three or four with their computers open and work.

"It was really powerful for us to sit outside, sit on a lawn together ... and figure out how to process this together," Perrotta said.

Deeply affected by the variety of experiences and connections she's forged at Vanderbilt, Perrotta has her sights set on law school next.

Head south from the student center and the Hustler office, and you’ll happen upon the sprawling medical center campus. After navigating a dizzying series of tunnels and elevators, you’ll wind up at the lab of Dr. Mark Denison, where breakthroughs in COVID-19 research have garnered international interest in recent years.

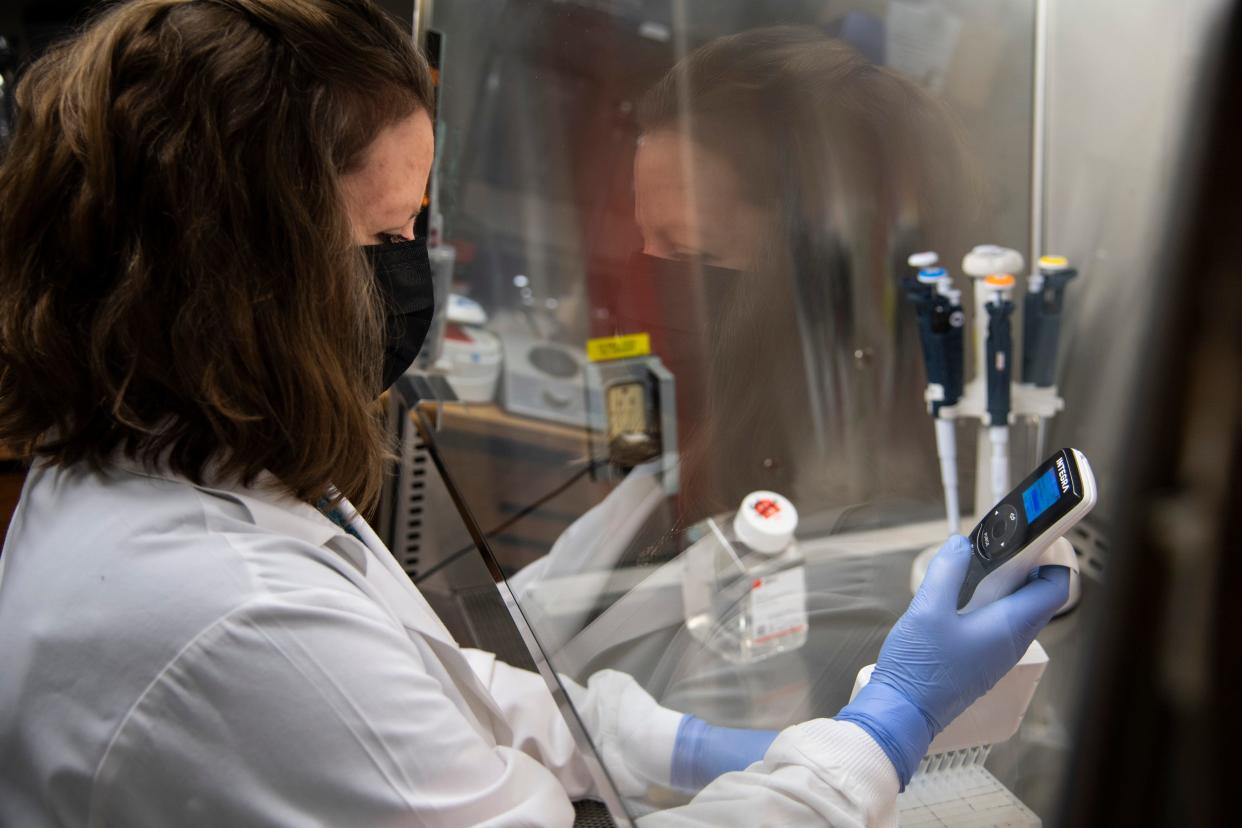

When Laura Stevens first came to work in Denison’s lab, she was struck by how engaging, excited and open to discourse the team was. As the pandemic raged, she helped conduct the lab’s vital research on developing COVID-19 antiviral treatments. She also helped conduct the trial for the Moderna vaccine, funded in part by a $1 million gift from country star Dolly Parton.

Stevens remembers the exact day she first saw signs the Moderna vaccine could neutralize the COVID-19 virus: May 9, 2020. She and her colleague Andrea Pruijssers were peering at backlit slides in their lab when they realized what they were seeing.

They started screaming in excitement, elated by the glimmer of hope in a dark time.

“It was 30 straight seconds of euphoria,” Stevens said. “Then it was right back to work.”

A vision for the future of Vanderbilt

Today, Vanderbilt University's endowment has grown to over $10 billion, supporting more than 13,000 students at 10 schools and colleges, and driving internationally recognized programs. While it’s impossible to summarize the role Vanderbilt has played in the Nashville community and beyond over the last 150 years, Diermeier, the chancellor, said he has high hopes for its future.

“We are in a moment now where there's so much change happening in higher education that we need to really rethink what a great university for the 21st century is," Diermeier said.

He sees the university's students as its true legacy. Alumni have gone on to become senators, business leaders, scientists, doctors, athletes and more.

"From Bach to baseball and everything in between," Diermeier quipped.

In the years to come he wants the university, which has been called the "Harvard of the South," to stand alone, instead of competing with others. He also wants it to stand the test of increasingly polarized times in the U.S. and around the globe.

A native German, Diermeier was no stranger to the power of institutions to divide or unite as he grew up in the shadow of the Berlin Wall.

He was 24 when the wall came down, popping champagne with fellow revelers atop it as the Brandenburg Gate opened in 1989.

“It was an incredible, unforgettable time," Diermeier said. "That shaped my interest in how institutions play an important role in business and society and politics."

He wove that sense of fascination and determination into the stories he told as he reflected on Vanderbilt's long, storied history and the path now ahead of it.

As its 150th year draws to a close, Diermeier is set on pushing Vanderbilt forward amid global conflict, lagging college enrollment nationwide and culture wars that challenge the value of a college education.

To sum things up, he repeated one of the university's unofficial mottos:

"We’re proud but not satisfied."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Vanderbilt staff reflect on Civil War start, civil rights, legacy