The untold story of the Hilton Head man killed on his bicycle

Alvin Singleton seemed to live on his bicycle, and he died on his bicycle Nov. 6.

The S.C. Highway Patrol says he was killed in a hit-and-run accident late that Sunday night on Palmetto Parkway on the north end of Hilton Head Island.

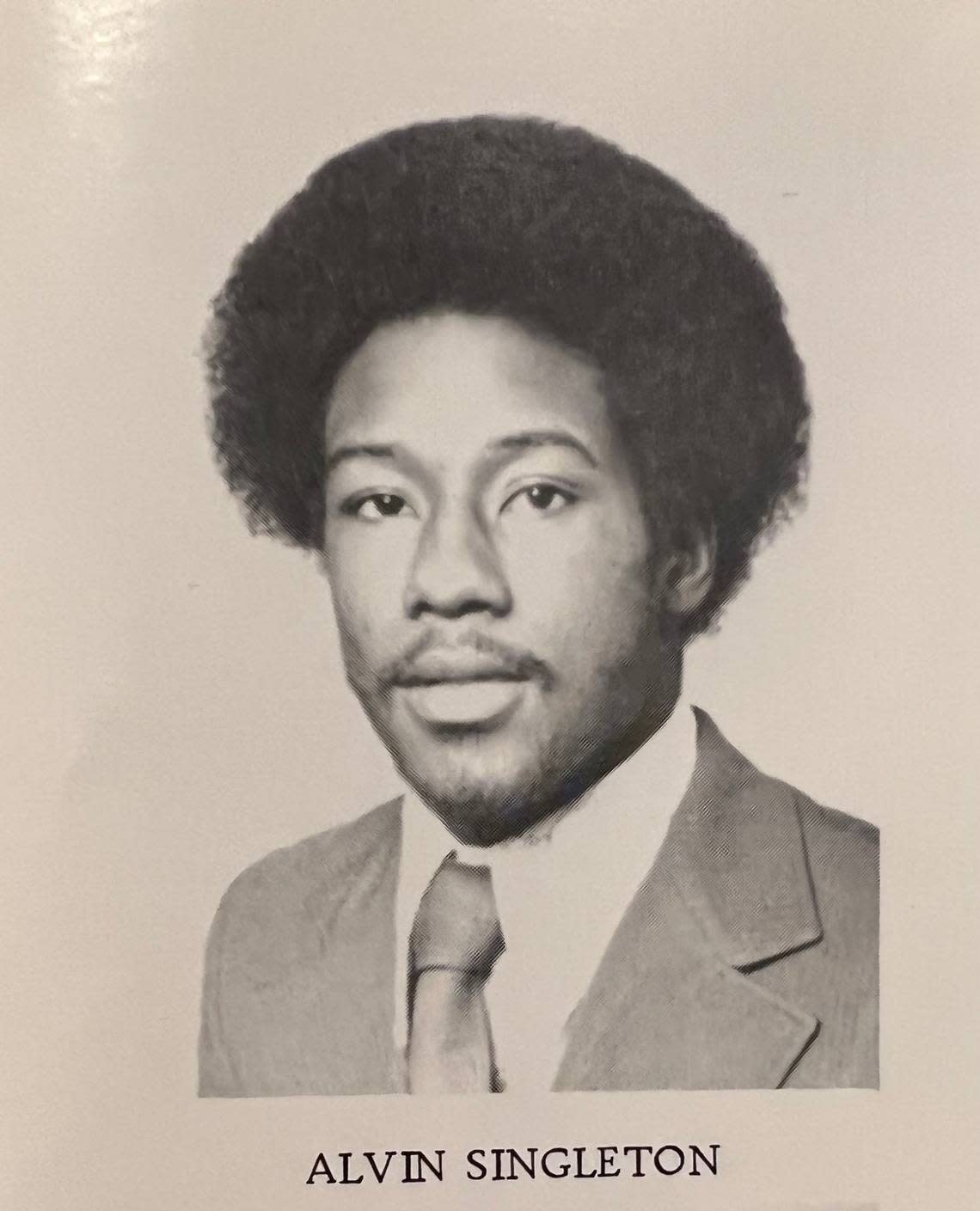

His death at age 67 shook his classmates in the H.E. McCracken High School class of 1973, where he was a star athlete who made good grades.

And it saddened the directors of two of the island’s social services agencies who treasure framed self-portraits that Singleton made photocopies of and sold for $5.

The Rev. Nannette Pierson, founder and director of the Sandalwood Community Food Pantry on Hilton Head, said, “Alvin Singleton was a big part of our Pantry family. Alvin arrived on his bicycle every Tuesday and when I would tell him, ‘Alvin, I love you no matter what!’ he would cry, and when I prayed he would just soften into the sweetest soul.”

Sandy Gillis, director of the Deep Well Project, said, “My guess is many, many people have seen Alvin, maybe talked to him, maybe were asked by Alvin if they could spare a dollar.

“Alvin covered the north end of Hilton Head on foot and on his bike like it was his premier sales territory. He’d visit Deep Well and ask for a soda, some hot dogs, and some bread, preferably sliced bread with no seeds.

“One time we had a big slice of yellow cake with chocolate frosting to share with Alvin. He was so happy to see that cake in his ‘travel food bag’ that he sat right down on the bench by Deep Well’s front door and proceeded to devour that big slice of cake in one sitting. He declared it very good cake.”

Singleton lived on his mother’s property off Marshland Road.

His sister Vernie said his life was complicated, and a source of both pride and frustration to the family.

It also was a life of hidden gems, and great promise.

HILTON HEAD LEGACY

Alvin Singleton was from one of Hilton Head’s oldest and most prominent families.

His great-great-grandfather, Namen Singleton, spent the first 12 years of his life in slavery, but started an inspiring legacy of land ownership and entrepreneurship on a remote Hilton Head.

Namen’s son Ezekiel was “able to envision the great potential that the land possessed,” according to a history of the family published in 2016 by Hilton Head Monthly magazine. “Having the forethought of its value as well as location, they developed the beach front property (in the area now known as Singleton Beach), and built pavilions as well as the Sand Dunes store, drawing Black people from as far away as Atlanta, Charleston and Savannah to the waterfront for entertainment and relaxation.”

Alvin was the son of Diogenese and Dorothy Singleton, who ran an Amoco service station on William Hilton Parkway in the Chaplin community, long before the Four Seasons Resort was built across the road.

“In 1943, a young Diogenese Singleton began a life dedicated to education and progress in a wooden rowboat bound for ninth grade at Penn School on St. Helena Island,” The Island Packet reported in a front-page story when he died in 2002.

Diogenese was a teacher at the three-room Robinson Junior High on Beach City Road, and then Michael C. Riley High School in Bluffton.

He was a mentor, philosopher, and great thinker who wrote frequent provocative letters to the editor. He also was a farmer on Hilton Head, specializing in peaches and pigs.

“Many of us used Mr. Singleton as our stabilizer,” said Thomas C. Barnwell Jr. “He was always available to give us good advice. There is no replacement for him.”

Vernie Singleton said they did not realize the impact his father’s passing would have on her brother.

THE ATHLETE

Ted Whitaker, the legendary track and field coach of Hilton Head and Bluffton, put Alvin Singleton in the highest echelon of athletes to ever come from this community.

In describing the great athlete Charles Kidd, Whitaker told me in 1978, “We’ve had a lot of athletes here, but Charles is right up there with the Joe Greenes and the Alvin Singletons.”

Singleton was 5-foot-8 and 160 pounds at the most, but so fast and quick that in his junior and senior seasons at McCracken High, he threw 13 touchdown passes, scored 16 touchdowns, returned six punts or kickoffs for touchdowns, and intercepted 26 passes.

Those were glory days for the Bulldogs, with Singleton at quarterback and running backs Michael Cohen and Henry Mervin behind him. On the line was one of the all-time best in Martin Govan.

In track, Singleton once ran the 100-yard-dash in 10.1 seconds.

He ran the second leg on a state champion 880-relay team, with George Powell, Mervin and anchor Mike Cohen.

He was the school’s first player selected by coaches to play in North-South all-star football game in Columbia, and the only player on the South team from a Class A school, the state’s smallest classification.

And he earned a four-year full scholarship to play wide receiver at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, North Carolina.

His parents did get to go see him play. But he did not finish school.

THE ARTIST

Alvin Singleton also was an artist.

He learned a good bit from two professors in Western Carolina’s large art department.

When Singleton had an exhibition of 11 paintings at the Hilton Head Library in 1978, the show was reviewed by longtime Packet art critic and accomplished artist Kathryn Hodgman.

Singleton told her his professors allowed students to work out their own ideas.

“But, according to Alvin, ‘they did not get into color.’ Alvin certainly did,” Hodgman wrote. “These are free and vivid in color interpretation: purple skies, red suns, brilliant greens.

“They are vigorous, original and inventive.”

Titles included “The Port Royal Cannon Base,” “Palmetto Dunes,” and “Mid-Atlantic Beach.”

“Alvin did, indeed ‘get into color’ in many of them,” Hodgman wrote. “He is free in his interpretations, with brick-colored skies covered with billowing white clouds outlined in gray; with bright orange beaches; with blue and black water patterns.”

She said Alvin Singleton the artist was discovered by a family friend, Virginia Kiah of Savannah, a portrait painter whose work has been shown in the United States Capitol.

She opened The Kiah Museum in 1959 in her mother’s home, dedicated to her mother’s role in civil rights activism, and was a board member of the Savannah College of Art and Design, which named Kiah Hall for her in a historic building that formerly housed the SCAD Museum of Art.

Singleton apparently sold all of his art, and a friend of the family is now trying to piece together a collection.

Sandy Gillis at Deep Well said she told Singleton when she purchased a copy of his self-portrait that his use of color reminded her of the work of Beaufort County native Jonathan Green.

She said, “Alvin could be a challenge. While he was physically pretty small, he was tough and wiry – and could be a little scary when he was agitated.

“But I’m going to choose to remember Alvin the way he was that day he found the giant piece of chocolate cake in his bag … a wide smile, with a few teeth missing, and delight dancing in his eyes.

“Rest in peace, Alvin.”

David Lauderdale may be reached at LauderdaleColumn@gmail.com.