The Unknown Librarian Who Saved Queer History

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

I’ve always loved public libraries. They were my refuge as an isolated, nerdy queer kid in the 1980s. They gave me my first jobs, and were the first places I found information about queer history. Limited, sure—but still better than anything I’d gotten from school, or my family, or on television, or anywhere else.

Unfortunately, these days public libraries are embattled spaces. My hometown of New York City is looking to cut $36 million from the library budget this year, a devastating blow to an already overburdened system. Librarians across the country have been attacked as groomers and pedophiles for simply allowing queer books on the shelves. Perhaps most troubling, Republican lawmakers and presidential hopefuls seem intent on driving queer content from the public sphere entirely—out of libraries and off school syllabuses. Somehow, for people who never seem to have set foot in a library in their lives, they understand this crucial truth: Destroying our history is the first step to destroying our present and future. As a result, independent and private queer archives—which may once have seemed quaint, parochial, or no longer necessary in our age of acceptance—now feel like our one essential firewall holding fast against the genocidal ’phobic fantasies of anti-queer bigots.

For decades, long before this current round of attacks started, these indie archives and their dedicated staff have worked to preserve and protect queer history against exactly this kind of threat. You probably don’t know the name Paul Fasana, but read enough LGBTQ history and he pops up in book after book over the last three decades—not in the text itself, but in the acknowledgments: Pink Triangle Legacies (2022);Language Before Stonewall (2019); Greetings From the Gayborhood (2008), Becoming Visible (1998). From 1995 until literally the week he died in April 2021, Fasana volunteered as chief archivist for the Stonewall National Museum, Archives & Library in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, one of the oldest and largest independent queer archives in the United States.

As Pink Triangle Legacies author W. Jake Newsome told me, “Fasana has done more to provide access to our queer pasts than anyone else I’ve known … Paul listened patiently as I described my project and then pointed me toward sources that helped me answer questions that I didn’t even know I was asking. He didn’t need a finding aid; it seemed that he knew every document, box, and item by heart.”

A working-class gay man and first-gen college student, Fasana came out in the late 1950s, while getting a master’s of library science at UC-Berkeley (where he later established a scholarship for queer students). After rising through the ranks at the New York Public Library, he moved to Florida in the mid-’90s and began the herculean task of organizing SNMAL’s holdings. Since 1972, SNMAL has been a crucial safeguard of queer history—particularly queer Southern history—but like all independent queer archives, its fragile existence has long depended on volunteers like Fasana, passionate pencil pushers who perform the inglorious yet absolutely necessary day-to-day work.

By the time Fasana came on board, SNMAL’s holdings had grown precipitously, particularly as it rescued vast collections from men dying in the first wave of the AIDS crisis. Out of a jumble spread across three different warehouses, Fasana knit the collections together into one usable archive—an archive that has been powering queer scholarship and community in southern Florida and across the country ever since. Today, in honor of Fasana and his partner, Robert Graham, SNMAL’s collection is known as the Fasana/Graham Archive.

According to Hunter O’Hanian, who served as executive director of SNMAL during part of Fasana’s tenure, “More than any other single individual, [Paul Fasana] is responsible for the richness of the vast archives at Stonewall. Thousands of pages in the archive bear his carefully handwritten notes in pencil … Future generations of scholars and researchers will owe him a debt of gratitude.”

Just how big of an archive are we talking? Stacked vertically, SNMAL’s collections would reach twice the height of the Empire State Building. Counting just the paper files alone, there are six million pages of material. And SNMAL is just one of the queer archives working independently, at the margins of financial solvency, to keep our history out of the trash and in the hands of people like me, and you, and those who come after us.

How many such archives exist is impossible to say, but it’s not a large number. Our community institutions expand and contract over time, growing, shrinking, founding, floundering. Dr. Mahesh Somashekhar at the University of Illinois at Chicago has been using the archives of the Gayellow Pages to come up with an estimate, but the numbers fluctuate wildly: 16 in 1976, 56 in ’87, 20 in ’96, 80 in ’08. Today, who knows?

One of the first such archives in the world was founded in Berlin in 1919 by the groundbreaking queer researcher Magnus Hirschfeld. Called the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (the Institute of Sexology), it was burned by Nazis in 1933. Around 20,000 books up in smoke—we have only some idea of what all was lost. But we know Hirschfeld and the Institut were on the forefront of trans medicine, social science, and activism. We know why the reactionaries came for us then; we know why they are coming for us now. It’s amazing how little can change in 90 years.

Recently, the photographer Matthew Leifheit has been documenting independent queer archives, from the large players like Stonewall to tiny personal shrines like the Christine Jorgensen Memorial Bathroom in Brooklyn. Leifheit feels a gravitational pull to these spaces. With the photos, he’s not trying to document their holdings, but “to pass along some of the emotion and wonder of discovering things in the archive.” He sees them as akin to the relics of saints, sitting at the intersection of myth and history.

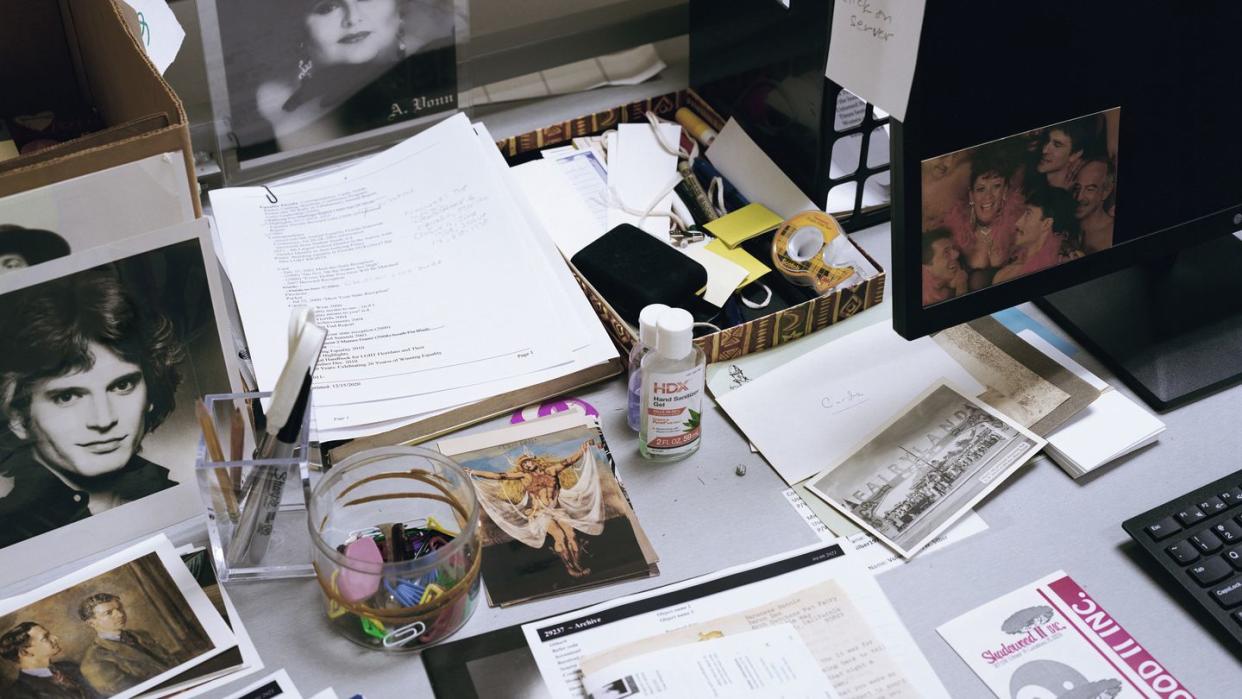

Leifheit arrived at SNMAL just after Paul Fasana died. It was so soon after, the chief archivist’s desk was still cluttered with the stuff of his life—the stuff of our lives. Look at them, look at them all looking back at you: the queens, the kings, the obituaries and unbroken hearts. They are our fragile, flammable legacy, and we can lay our hands on them only because of the work of people like Paul Fasana.

You Might Also Like