From unicorns to unicorpses: Why billion-dollar startups and even VC firms keep imploding

In its prime, the Seattle-based freight network company Convoy was one of tech’s esteemed startup success stories.

Two Amazon veterans set off on their own in 2015 to build a platform that would connect shippers with carriers who had extra, unfilled space on their tractor trailers—making supply chains more efficient and reducing emissions. Flush with more than $1 billion in equity funding and debt it had accumulated over the years from some of the tech industry’s most prominent investors, entrepreneurs, climate activists, and lenders, Convoy had at one point hired 1,300 employees and built out a network of more than 400,000 trucks across the country.

By 2022, Convoy had started to dabble in a wide array of business lines outside its initial purview: a fintech offering for quick payments; a fuel card for discounts on diesel; a trailer-rental service. By the end of that year, Convoy’s gross margin had grown to a respectable 18%, according to a document seen by Fortune. But its hefty fixed expenses, including steep engineering and product team costs and an expensive lease in Seattle, were weighing down its financials, according to someone close to the company. Those expenses kept Convoy from turning a net profit.

Three years ago, that may not have been a problem. But the market had turned. Last October, Convoy became one of many casualties of a painful reset within the private markets. Just 18 months away from a fresh $410 million cash infusion from a Series E round and line of credit, Convoy suddenly laid off nearly everyone on its staff, shut down its core business, and, shortly after, raffled off its technology platform to another freight startup. In a memo to employees that was obtained by GeekWire, its CEO, Dan Lewis, said Convoy had hit a “perfect storm”: a collapse in the freight market, paired with a “dramatic monetary tightening” that “dampened investment appetite and shrunk flows into unprofitable late stage private companies.”

Convoy’s assets are now in foreclosure, and it is in litigation with employees who say they didn’t get paid. Its investors—including Alphabet’s growth investing arm CapitalG; Greylock Partners; Y Combinator’s growth stage fund; Amazon founder Jeff Bezos; Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff; and Al Gore’s climate fund Generation Investment Management, to name a few—lost the entirety of their investment, according to The Information. Convoy, whose investors determined it was worth a heaping $3.8 billion as recently as April 2022, is now worth nothing at all.

The world of startups is well-accustomed to failure: Approximately nine in 10 shut down. But those failures rarely attract the attention of the broader public. They tend to happen early in a startup’s life—when the people who run it are still in trial-and-error mode. As a company gets bigger and achieves enticing revenue growth, it gets more love from some of the thousands of thick-pocketed venture capital firms that write checks so companies can scale quickly. As those investors pour in more and more capital, failures become less frequent.

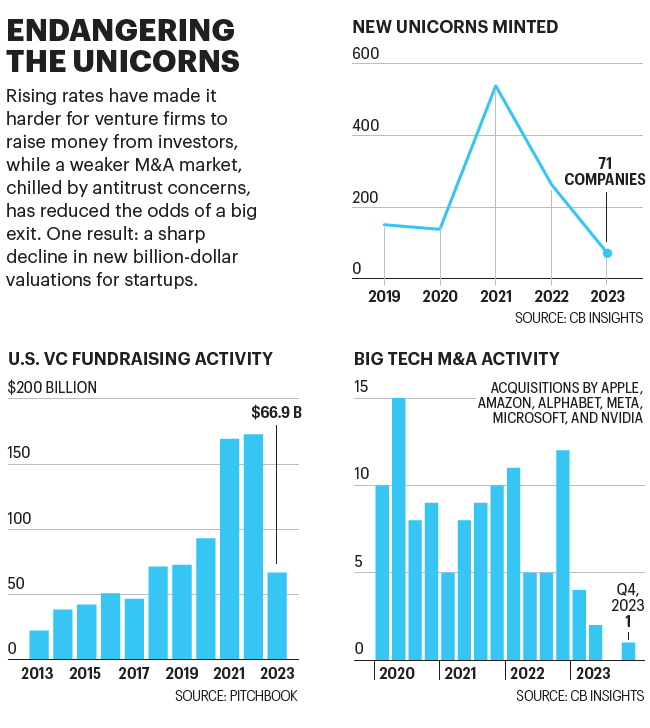

Or at least they used to. Since the first quarter of 2022, everything has changed. Macroeconomic forces have refashioned every link in the chain of the startup ecosystem. Those changes are now rippling through private markets in what has turned into a reckoning for startups—and especially for unicorns, the privately funded companies valued at more than $1 billion that are Silicon Valley’s most elite and prized darlings.

“It’s one thing to fail when you’re a small company and you fail to get product-market fit,” says Geoff Love, head of venture capital at Wellcome Trust, which has invested in several venture funds, including those at Accel and Venrock. “It’s quite something else to fail when you are at a valuation in the many billions and have raised hundreds of millions of capital. That’s awful.”

The atmosphere has turned undeniably sour for startups. Just two years ago, founders were elbowing investors out of their oversubscribed funding rounds; now some are struggling to raise at all, and are facing the harsh reality that their businesses are worth much less than they thought. The IPO market has dried up relative to 2021, and M&A deals have become harder to secure and close—keeping investors from being rewarded for their bets. After more than a decade of an overabundance of capital, cash has suddenly become scarce.

So far, the market has seen only a handful of unicorns formally call it quits. Health startup Olive AI shut down in October. Design startup InVision said it would discontinue its business in January. Modular building company Veev announced a shutdown in November. Of course, there was the high-profile, scandalous blowup of the crypto exchange FTX, which shut down in 2022.

But much of the pullback has been quietly playing out behind the scenes. While macroeconomic changes immediately sway the share prices of publicly traded stocks, their impact takes a while to appear in private markets. Private companies aren’t required to disclose financials or material business changes to the public, so dramatic slowdowns aren’t always apparent—until a sudden announcement or press report announcing major layoffs or a full-on demise.

Nearly two years after the IPO markets effectively closed to most venture-backed startups, we’ve only just recently begun to see the full effects. When new funding dried up in 2022, many of these companies still had about 18 to 24 months of runway before they would run out of cash, according to Anand Sanwal, executive chair and cofounder of CB Insights, which conducts research on venture-funded businesses.

“We’re just coming up on the end of that window,” he says, noting that he’s expecting an “intensification” of shutdowns and acqui-hires in the first part of this year.

The reasons for failure at every company are different. There is no direct link from Convoy, which was facing enormous headwinds from a freight recession, to FTX, whose founder Sam Bankman-Fried was eventually convicted of multiple counts of fraud. But one thing is for certain: When capital is suddenly hard to come by, the wheat is always separated from the chaff.

It wasn’t long ago that the term “unicorn” went from metaphor to misnomer.

Until the past decade, companies rarely became so valuable when they were private. That’s why “unicorn” was first coined in 2013—if a company could achieve a valuation of $1 billion as a private company, it was a rare badge of success. When Fortune published a cover story about these burgeoning behemoth startups in 2015, there were only around 80 that had joined the $1 billion club.

Now there are more than 1,200, spread out around the world, according to CB Insights. And “unicorn” hardly seems like the right label for some of today’s private-company successes, which are scaled more like blue whales. Elon Musk’s space company SpaceX boasts a reported valuation of $180 billion, and TikTok parent ByteDance one of $225 billion, while ChatGPT creator OpenAI could reportedly notch a $100 billion valuation in its next funding round.

So what led to the unicorn boom? Low interest rates made the venture sector more enticing to investors, as other, less risky alternatives became less lucrative. Venture returns were also far exceeding those of the public markets, which drew new investments into the space, according to Theresa Hajer, head of U.S. venture capital research at Cambridge Associates, which advises venture funds’ limited partners. Then there was the success of startup IPOs, which drew in hedge funds and mutual funds like Coatue, Fidelity, and T. Rowe Price, all aiming to take advantage of pre-IPO growth by becoming private-stage backers of companies like Uber, Snap, and Pinterest.

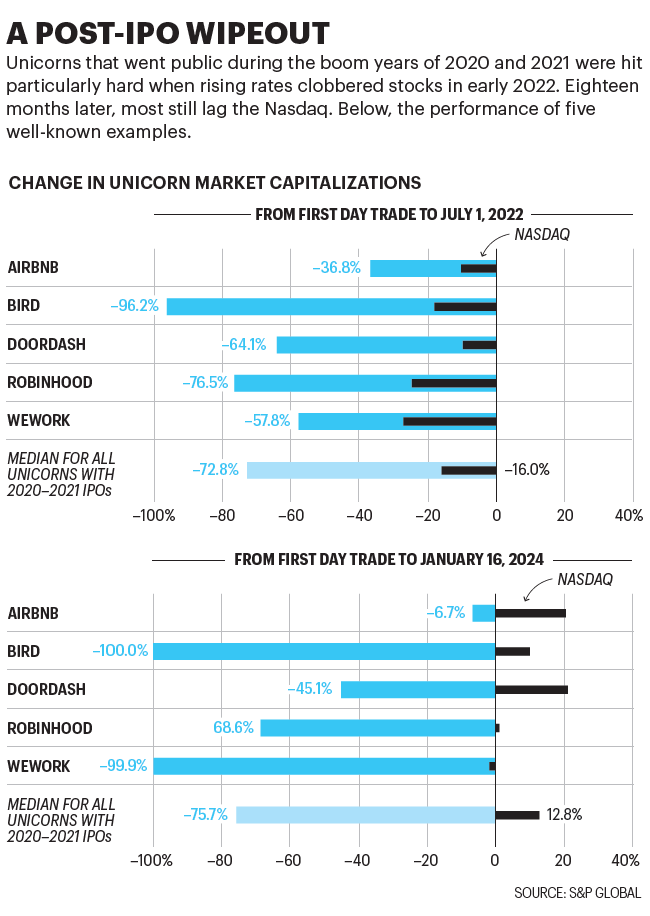

Add the pandemic-induced tech boom in 2020 and the extraordinary $2 trillion stimulus to that equation, and we ended up with what you could either describe as two banner years for venture capital or a nonsensical frenzy of record funding, record exits, and record valuations in 2020 and 2021. With capital freely flowing throughout the ecosystem, companies with hardly any revenue—in some cases, none at all—were going public at more than billion-dollar valuations during that period, amid unprecedented demand from investors.

“There were companies that were doing $5 million in revenue that were being valued at $1 billion,” CB Insights’ Sanwal says, adding, “We were seeing 100x, 200x multiples.”

But between February 2022 and the end of 2023, the economic climate darkened. The Federal Reserve gradually raised its baseline interest rate more than tenfold, to 5.33%. There was a steep correction in the public markets, with software, internet, and fintech stocks dipping well below where they had traded pre-pandemic. War broke out in Ukraine (and, more recently, the Middle East). Tensions heightened between the U.S. and China, where a series of VC firms had made a fortune.

In May 2022, Sequoia Capital blasted out a slide deck to its portfolio companies, warning that the tech industry faced a “crucible moment.” It was one of a handful of ominous warnings the firm has issued over the years when its partners anticipated a correction (not always accurately). But this warning was quickly echoed by other firms, including noted startup incubator Y Combinator. “The era of being rewarded for hypergrowth at any cost is quickly coming to an end,” Sequoia partners warned.

Rising interest rates, in particular, tend to stymie venture-capital activity. Interest rates are directly correlated to discount rates, which investors use to calculate the present value of future cash flow of a company—which in turn influences valuation at later stages. Higher rates also mean that capital is more expensive to borrow, making it more difficult for startups to maintain a fast pace of growth. Beezer Clarkson, who leads Sapphire Partners’ investments into venture funds, puts it simply: “The free money stopped.”

Rising rates pose another threat to startup fundraising, though their impact is less immediate. Higher rates make less-risky assets, like fixed income or infrastructure, more attractive to the pension plans, endowments, charitable organizations, family offices, and sovereign wealth funds that usually invest with VC firms. These backers, called limited partners or LPs, are the ones whose money is ultimately funding the whole ecosystem. Historically, research has shown that rising rates lead to less LP investment in venture capital—and less money going into venture funds ultimately means less money going into startups.

We’re seeing all of this play out in real time, to devastating effect. When public markets faltered, unicorn darlings that had gone public in the previous two years plummeted in value. Buy-now, pay-later company Affirm, which went public in January 2021, saw its stock drop from a peak of more than $168 per share to around $30 by mid-March 2022. Private companies were left with valuations that no longer seemed realistic relative to their public peers; the IPO market effectively closed in 2022, as that mismatch erased potential demand for their shares. That year, there was a 95% reduction in proceeds from companies going public in the Americas versus 2021, according to EY’s Global IPO Trends Report.

Only a couple of growth-stage startups have tried to go public since then—despite there being a slew waiting for the right time, including fast-fashion retailer Shein, social media site Reddit, and data intelligence company Databricks.

There’s good reason to be shy. Instacart was forced to take an enormous haircut, clipping its valuation on several occasions before its IPO last September. Since then, shares of the grocery delivery startup have fallen more than 30% as of mid-January. The company now has a market capitalization of about $7 billion—a remarkable discount to the $39 billion valuation Instacart boasted as a private company in 2021.

“There’s a vast majority of companies who raised these mega rounds in 2021 who will probably never be worth, at any point in time, the valuation that they were given” when they were private, Jamin Ball, partner at venture capital firm Altimeter Capital, said of software companies on the 20VC podcast earlier this year. The challenge, he continued, is what to do when you come to that realization.

“The euphoria can happen really quickly, and the downturn—the valve shutting off—can also happen really quickly.”

Beezer Clarkson, who leads Sapphire Partners

Meanwhile, Big Tech companies including Google, Meta, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon have retreated from M&A deals as they tighten their budgets. And antitrust regulators have become more aggressive in challenging acquisitions they say are anticompetitive. In December, Adobe called off its $20 billion megadeal to acquire the design unicorn Figma after facing backlash from regulators in the European Union and the U.K. That was shortly after the U.S. Federal Trade Commission won a court appeal that led the biotech company Illumina to divest the cancer-test startup Grail, which it had acquired for $7.1 billion two years prior.

The lack of funding and dried-up acquisition market played key roles in the demise of Convoy, which was seeking a buyer in its final hours. “We spent over four months exhausting all viable strategic options,” Lewis, the CEO, wrote in his memo to employees. “M&A activity has shrunk substantially and most … logical strategic acquirers of Convoy are also suffering from the freight market collapse.”

The shift in the market has led venture firms to radically mark down their investments in their funds. But a lack of IPOs and M&A deals is causing another problem: Venture funds aren’t able to return money to their own investors, the limited partners. That leaves the LPs either overexposed in this high-risk sector—and thus unwilling to put in new money—or without liquid capital to reinvest in new funds. And that breaks another link in the chain of startup capital.

“Every LP that I know is doing this math right now,” Sapphire’s Clarkson says, noting that LPs are calculating whether the cash their venture firms call to invest will outpace distributions they get from startup exits, and how much money they have temporarily trapped in the venture capital system. She adds: “The rational human behavior is to concentrate your dollars into the managers you have the highest conviction in.”

These new realities make it especially difficult for new venture firms and managers to raise their own funds right now. (Last year was the worst time in 10 years to try to raise a first-time fund, according to PitchBook data.) They also put pressure on the fundraising efforts of some of the billion-dollar firms that have raised megafunds in the past few years. In some isolated cases, venture firms are shutting down or deciding not to raise new funds. OpenView, a 74-person firm based in Boston, started to wind down its operations in December. More recently, hard-tech fund Countdown Capital told investors in January that it would shut down, according to TechCrunch.

“The overall business takes a while to build and to produce exits, but the euphoria can happen really quickly, and the downturn—the valve shutting off—can also happen really quickly,” Clarkson says.

Who will succeed and who will fail in this environment? That’s the question keeping many investors on the sidelines, waiting until they can be more certain of what a company is worth, or whether it will survive.

Bryan Roberts, who leads the storied early-stage venture firm Venrock, closed a $650 million fund in January, larger than the three $450 million funds it raised over the past decade. This isn’t an entirely bullish move; it reflects his belief that there will be fewer investors willing to back its companies in later rounds, and that Venrock will have to put more money into those it wants to support.

“Every investor on the planet is going to have a set of companies that they don’t believe in and either shut down or try to sell for very little,” he says. “And they’ll have some that they say, ‘No, I think this is worth it. And I’m going to take an added dose of risk of capital and risk to my reputation and my performance of my fund and my firm to give this company a shot at realizing their vision.’ ”

Roberts says Venrock’s choices about which startups to back will be centered on the people who run them, and whether they are doing something differentiated in the market.

Growth investors, who invest when a company is further along in its business, are thinking more about numbers and financials, and whether companies will be able to control their costs and become profitable.

“Every investor on the planet is going to have a set of companies that they don’t believe in and either shut down or try to sell for very little.”

Bryan Roberts, Venrock

“We’re seeing a fork in the road between those companies who were able to reset their cost base to align with slower market growth, and those who were not,” Lila Preston, who leads growth-stage private investments at Al Gore’s Generation fund, wrote in an email to Fortune. “A lot of this has come down to business model, which influences the scale required to get to profitability and the funding required to get to that scale.”

The data shows that startups in the AI sector have the best shot at getting funded now, and are securing the highest valuations. The median Series B valuation for AI companies is 59% higher than non-AI deals, according to CB Insights, and median valuations are 21% higher for AI companies at the seed stage. However, some investors and limited partners suggest there may be more excitement around AI than is warranted. “Venture is an industry that loves the hype cycle … There’s always going to be something, and this seems to be it,” Clarkson says.

Companies that are building something “mission-critical”—tools and technologies that enterprises can’t afford to cut, such as cybersecurity—also have a good shot at being more resilient, according to Cambridge Associates’ Hajer.

The tech industry has always attracted optimists. That characteristic is often necessary to build a company in a high-growth, high-fail-rate world. But those who are best positioned to get through 2024 may be those who exercised restraint and didn’t get carried away with the markups on private tech shares that made so many founders rich on paper just a couple of years ago—founders who stayed disciplined with hiring decisions and with the number of shiny high-risk projects they took on.

“The companies that I admire or respect don’t really get affected by the cycle,” says Josh Reeves, cofounder and CEO of Gusto, an HR tech services platform last valued at approximately $9.6 billion in 2022. “You always want to be building a good business. You always want to have good unit economics.”

He adds: “What matters more is focusing on what’s in your control. And that actually doesn’t really change based on the cycle.”

This article appears in the February/March 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline, “Running out of oxygen.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com