U of M's undergrad student body is 34% first-generation. Here's how the school supports them

More than two decades ago, Agustin and Erika Solis moved from Mexico to the U.S. and started a family. But life wasn’t easy. Neither had college degrees and finding stable work was difficult. The family moved from city to city as Agustin took warehouse positions and Erika raised their children.

Financially, they struggled. At one point, they lived in Erika’s sister's garage.

But growing up, Amairani Solis, their oldest child, wasn’t aware of her family’s challenges, because her parents strived to make sure she and her siblings felt supported and comfortable.

“They always gave me as much as they could,” she said. “They worked really hard, in order for me to have any opportunities.”

Those opportunities came with high expectations. Agustin and Erika pushed their children to succeed academically, determined for them to go to college. The couple hadn’t gotten this chance ― but for Amairani and her siblings, things were going to be different.

“They would be like, ‘You have to make good grades,’” she said. “If I got a low, bad grade, I’d get in trouble for it. College was always the expectation.”

Inspired by her parents, Amairani worked hard. She earned As and Bs in high school and joined clubs. When it came time to apply for colleges, she did her research and looked thoroughly at her options. It wasn’t long before she started receiving acceptance letters, which her parents proudly kept.

The University of Memphis made a particularly enticing offer. Amairani was accepted into its First Scholars program, a competitive offer for first-generation college students that would provide her with a $2,500 scholarship per semester for four years. The funds would cover a significant portion of her tuition, and Memphis wasn’t foreign to her. She had been born the Bluff City, and her family had settled in nearby Southaven.

In fall 2022, Amairani began as a freshman studying computer and electrical engineering at U of M ― where she joined thousands of other first-generation college students enrolled at the university.

At U of M, about 34% of undergraduate students are first generation, which means their parents either didn’t attend a four-year college or university or didn’t earn a degree from one.

The majority of these students come from low-income families, and often, their paths to success can be riddled with barriers. Covering the cost of tuition is challenging; many of the students are simultaneously full-time students and full-time employees. They have fewer resources than some of their counterparts and less guidance. If someone is the first member of their family to attend college, what point of reference do they have for navigating through it?

“You don't know what you don't know,” said Jacki Rodriguez, director of the U of M Office of First Generation Student Success. “They're trailblazing, and they have to figure it out while they're going through it. That can sometimes put you behind a little bit.”

Then there’s the imposter syndrome.

“The imposter syndrome lives in the mind of every first-generation student ― that feeling of, you’re not as good, you’re not as smart, as anyone else around you," Rodriguez said.

It was a feeling Rodriguez experienced when she enrolled at U of M about 25 years ago. And it’s one Solis wrestled with when she began her engineering coursework.

Many of her fellow students had parents or relatives that were engineers. When discussing a difficult question, one said, “Oh, I can just ask my uncle, and how he does this, because he’s already an electrical engineer.” They seemed well-connected and “crazy smart.” Daunted, Solis began to question herself. She wondered if she even deserved the scholarships she was receiving.

But Solis stayed focused and worked hard. She told herself, “There’s a reason I’m here, a reason I got accepted into this program.” She won a campus-wide essay contest for writing about how her family had helped her succeed ― a victory that provided her and her parents with a fancy meal, the chance to meet U of M President Bill Hardgrave and box seats at a Tiger football game.

And she received significant support from the Office of First Generation Student Success, located in Mitchell Hall on U of M’s main campus.

U of M’s first-generation office, Rodriguez explained, is nationally recognized for its work, and has trained over 300 other universities on how to effectively support first-generation students.

“We're trying to make sure all of our students are on the same firm ground,” she said. “They're having equal access to education and equal access to resources.”

Added Gage Farris, a first-generation sophomore, and First Scholar, like Solis: “There is a lot of support on campus, and all you have to do is walk down the hall, or walk into this building, and you’ll be able to find it.”

The office uses a holistic support model. Each student can ask for a peer mentor who is also first-generation and has faced similar circumstances. They can receive academic support and counseling and are provided with networking opportunities.

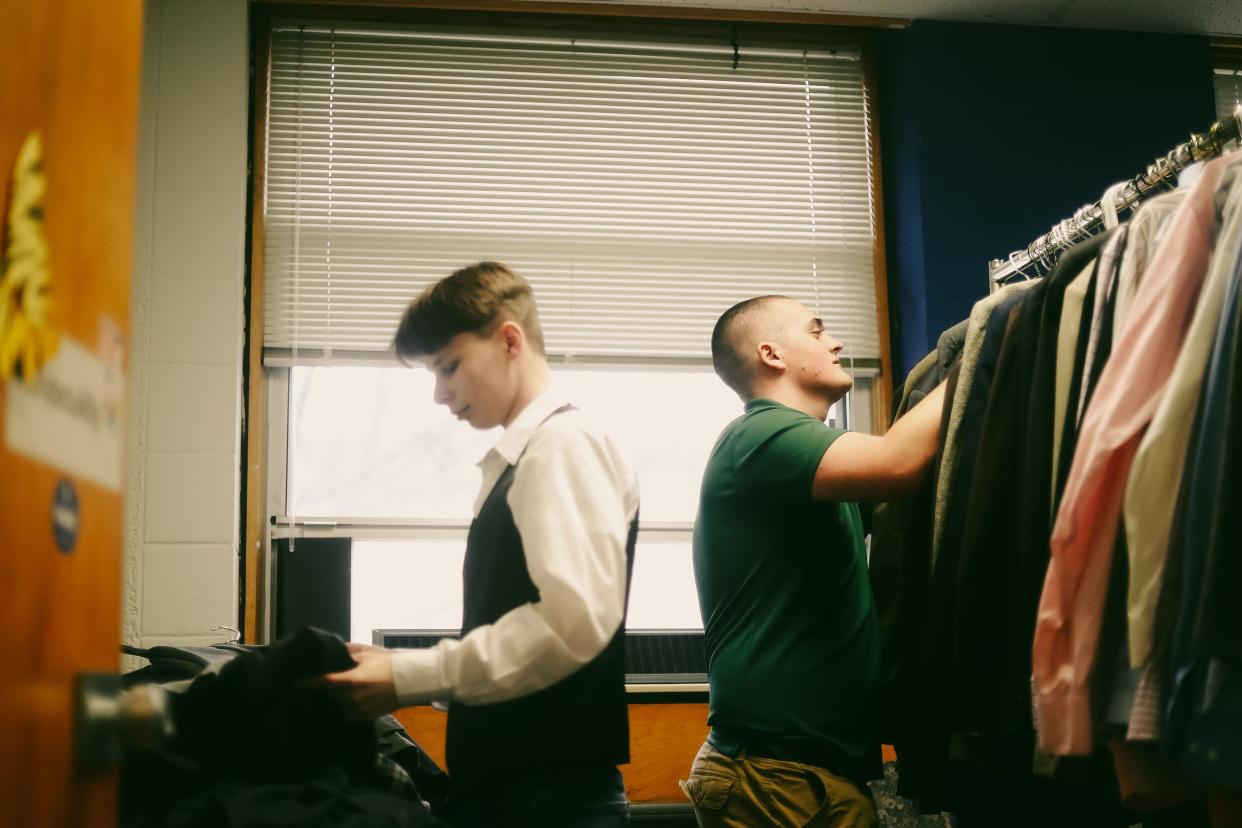

First-generation students also have access to the office’s career closet, a vast wardrobe of professional attire full of free outfits for interviews and career fairs. There’s everything from suits to dresses to blouses to ties to shoes. The office stocks the closet through donations and clothing drives, with U of M holding one in early March that brought in over 2,000 items. Typically, the career closet has something for everyone. But if it’s missing something, Rodriguez and her team will make a call to obtain the needed attire.

It's an important offering for students who wouldn’t necessarily have professional clothing without the career closet.

“There's an amount of confidence that comes when you have a nice suit… You have power,” Rodriguez said. “We want those students to feel that… We want them to be confident when they go into the interview, when they go into the career fair, we don't want them to feel like they're at a disadvantage.”

The office also offers a significant number of scholarships, which are perhaps most important in leveling the educational playing field. Each year, 20 incoming freshmen are accepted into the First Scholars program that Solis and Farris are a part of, which means there are 80 students in the program at any given time.

U of M news: Former Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland named next dean of U of M Law School

The $2,500 in scholarship funds these students receive each semester adds up to $5,000 each academic year and $20,000 over four years ― not enough to cover the entire cost of tuition, but enough to provide a major boost.

In recent years, the office has also offered the Opportunity Scholarship, a financial award designated for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program students. These students, who came to the U.S. as children, must pay out-of-state tuition, and they aren’t eligible for federal or state financial aid. But, the Opportunity Scholarship has generally brought the cost of their tuition down to about $2,000 per semester. Since the program’s inception in 2016, 89 students have received the scholarship.

And there are other scholarships specifically designed for first-generation students. In the 2022-23 academic year, U of M awarded 300 first-generation scholarships, including the First Scholars and Opportunity awards. However, while the office awarded 300 first-generation scholarships last year, there were over 4,600 first-generation students.

“We have thousands and thousands of first-generation students,” Rodriguez said. “But we do have a limited number of scholarships.”

For First Scholars, entrance is particularly competitive. The office received over 300 applications for the program in the 2022-23 academic year, but can only accept 20 students per cohort.

“That gives you an idea of that want and the need for these scholarships,” Rodriguez said.

Many first-generation students are eligible for other scholarships that aren’t first-generation specific, and the bulk are eligible for the need-based Pell Grant. But, finance remains a significant barrier, with students often working long hours to help cover the cost of tuition.

When Rodriguez was a student at U of M, she worked three jobs.

Most First Scholar and Opportunity scholarship recipients are employed too. On average, the students in these programs work 23 to 28 hours a week, while taking 15 or more credit hours per semester. Both Solis and Farris have jobs on campus, and Solis also works at a Walmart on the weekends.

Related: University of Memphis names former FedEx exec Michele Ehrhart next communications chief

But the scholarship programs do ease the financial burden ― and they could help improve student performance.

The overall first-year retention rate for first-generation students at U of M is 29.8%. But for First Scholars recipients, it’s 93%, and for Opportunity Scholarship recipients, it’s 100%.

There are also significant differences in the graduation rates. The overall four-year graduation rate for first-generation students at U of M is 29.8%, and the five-year graduation rate is 40.9%. For First Scholars recipients, the four-year rate jumps to 55%, while the five-year graduation rate more than doubles, to 88.9%. For Opportunity Scholar recipients, the differences are even more dramatic ― 96% of them graduate in four years or less.

“I do wish the department was bigger,” Farris said of the first-gen office and First Scholars cohort. “Because right now we can only accept 20 [in First Scholars]. Even if it was just to 30, that, I believe, would make another significant impact.”

Farris and Solis are grateful to be among the select number of students who are part of the First Scholars program, and though both are sophomores, they’ve already thought about what it will be like to graduate, with their families watching.

Farris’ mother started college but never completed it, and as her son grew up, she encouraged him to succeed academically while she worked hard to support him. It was important to her that her children attend college.

And just a few years from now, she’s set to watch Farris receive his degree.

“Judging by how she reacted at high school graduation,” he said, “she'll probably cry.”

Solis, too, is looking forward to graduation.

“It makes me emotional, because I will be the first one in my family to graduate and walk the stage and get a diploma, ready for my career,” she said. “My parents always talk about how, ‘Oh, I'm going to have an engineer in the family.'”

She does sometimes feel pressure. She is, after all, trying to set an example for her younger siblings, and the expectations are high. But that, she explained, is okay.

“It gets hard,” Solis said. “But I'm doing this because I want to do this. I'm doing this because I want to make something. I want to create the path for everyone.”

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: How University of Memphis first-generation students are supported