U.S.-based online food stores were meant to help Cubans. Why are they selling Havana Club?

Online supermarkets allowing Cuban Americans to pay for food for their families in Cuba have become a lifeline for many on the island during the pandemic, helping them survive amid widespread food shortages.

Similar to websites offering groceries online, these platforms allow U.S. customers to select and pay for products that usually cannot be found in island stores, such as meat and milk, that will then be delivered to the address of the recipient in Cuba.

But some of these online stores have become a marketplace for flagship Cuban products such as Havana Club rum produced by state companies and enterprises that are private on paper but maintain their links with the government, raising questions about compliance with the U.S. embargo and the legal basis for the business model.

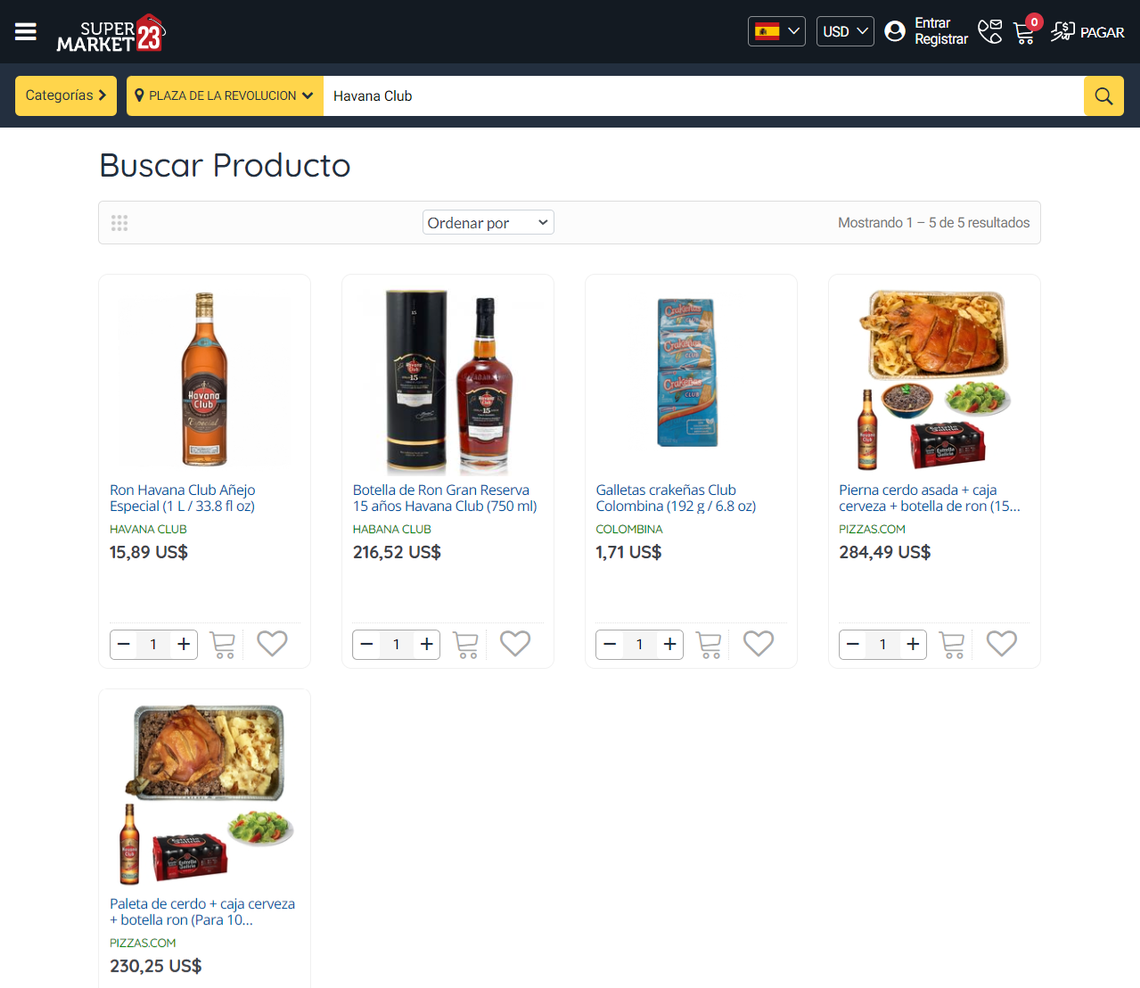

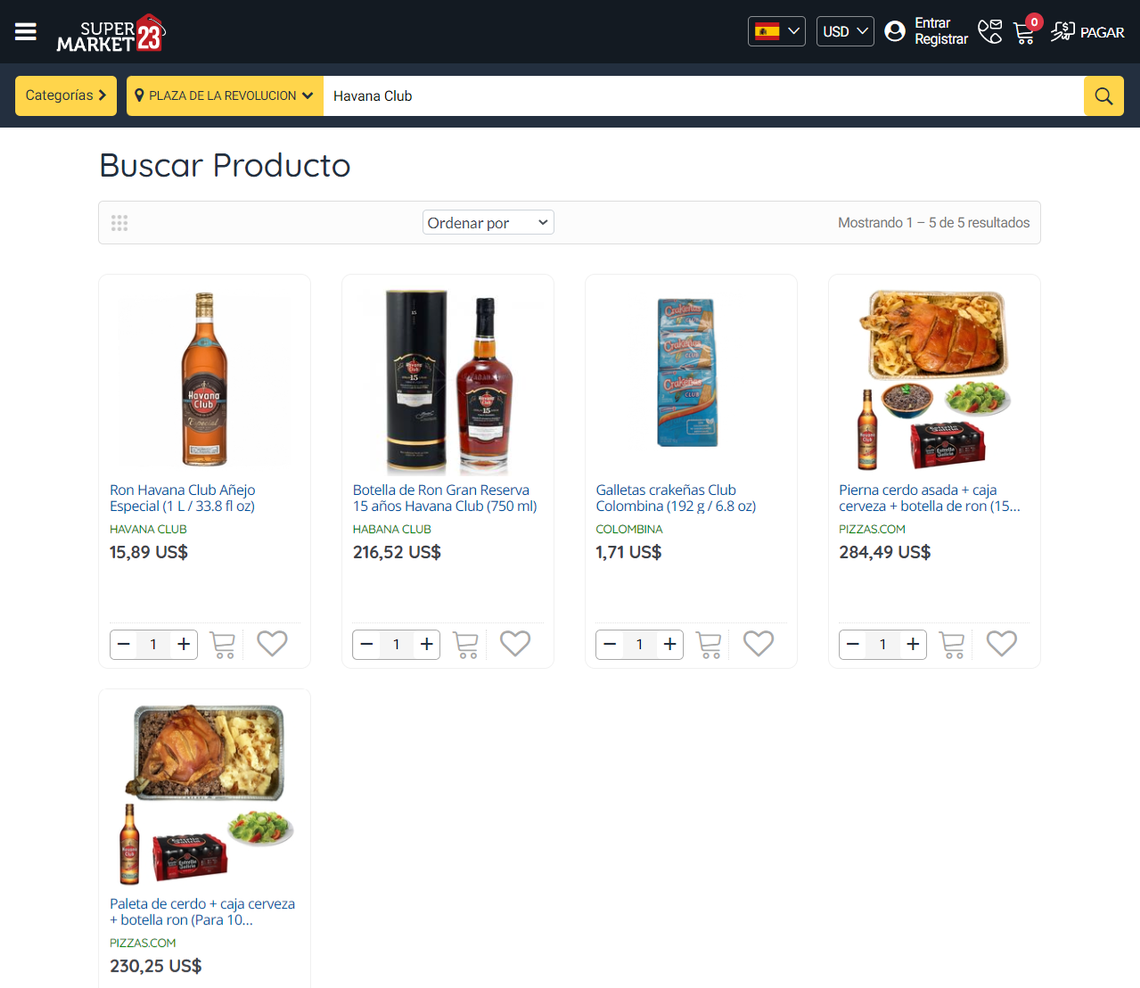

For instance, Miami-based Cubamax, a Cuba travel agency now offering food products for Cubans on the island, offers four different brands of rum made in Cuba, including Havana Club. Supermarket 23, another e-commerce platform registered in Florida, is marketing a $216 bottle of Havana Club Gran Reserva. The same bottle is $239 on Cubamax.com.

Other products manufactured by Cuban companies are for sale, as well.

Cubamax is selling well-known Cuban coffee brands such as Cubita and Serrano and buffalo ground beef from Empresa Pecuaria Genética El Cangre, a state enterprise in the town of Guines, near Havana.

And Supermarket 23 is offering products marketed by the state’s Empresa Integral Agropecuaria in Ciego de Ávila.

How Cuban rum and other state-made goods ended up being marketed to U.S. customers despite embargo regulations is a question some activists are posing to authorities.

Salomé García Bacallao, a Cuban human-rights activist, recently filed a complaint with the Office of Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody against Supermarket 23 for alleged embargo violations. García Bacallao said she wanted to call attention to the company’s activities following a report by Cubanet, an independent news website, showing the e-commerce platform was selling food products from Alcona, a Cuban state enterprise connected to Cuban general Guillermo García. References to Alcona products have since been deleted from the website.

García Bacallao’s complaint and at least three others involving Supermarket 23 “are currently under active review,” the Office’s deputy communications director, Kylie Mason, said.

Supermarket 23 is owned by Cuba-born Anibal Quevedo, the founder and CEO of Canadian-based Treew, which runs Supermarket23.com and several similar websites such as Treew.com and Supermarket.treew.ca. Under different names and registered in Canada and Spain, his online store has been in business for several years.

An Angola war veteran, he was the former director of the Cuban government’s first e-commerce website, Cubaweb.cu, in the 1990s. He also sold Cuban cigars online on his website Unicoshabanos.com.

He could not be reached.

It is unclear if Supermarket 23 conducts business in Florida, where Quevedo’s son, Anibal Quevedo Jr., registered it as a limited liability company in 2016. Quevedo Jr. did not reply to calls, text messages and emails left by the Herald.

Reached by phone, Carlos Trujillo, owner of Cubamax, said he was busy and couldn’t take calls from the Herald. He did not respond to questions sent by text message.

All references to Havana Club and other Cuban rum brands have since been deleted from the Cubamax.com website.

How does the business model work?

Online grocery shopping for residents in Cuba has become a popular business but one that gets complicated because of the U.S. trade embargo on Cuba.

The embargo prohibits all transactions involving Cuba unless they’re authorized by the Department of the Treasury or other laws. However, companies can export food and medicines to Cuba legally, and import certain goods (including most food products) and services produced by independent Cuban entrepreneurs.

The State Department warns that those importing goods from private businesses in Cuba “must obtain documentary evidence that demonstrates the entrepreneur’s independent status” or evidence that “demonstrates that the entrepreneur is a private entity that is not owned or controlled by the Cuban government.”

U.S. persons can also request that the Treasury and the Commerce Department authorize a particular activity or transaction with a special license, which tends to be very specific.

Not all these platforms follow the same model. Katapulk.com, for example, also offers private businesses in Cuba the opportunity to sell their products on its platform.

Hugo Cancio, the Cuban-American owner of Katapulk, said in a statement that most of the products he sells through the online store come from the U.S.

“The vast majority of products on our platform are legally imported from the U.S., brands recognized by our customers at reasonable prices,” he told the Herald. “Katapulk is more than an online store; it is a marketplace where there are more than 145 independent stores that offer a wide variety of products and services.”

While these online platforms might be operating under a combination of general and specific licenses, experts and lawyers note that the regulations do not seem to authorize companies under U.S. jurisdiction to market and sell to U.S. customers products made by Cuban state companies or businesses with links to the state.

“Everything the administration has done and it’s going to do involves supporting the non-state sector,” said John Kavulich, the president of the U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council. “If someone uses a general or specific license to support the purchase or market Cuban government products, they are leaving themselves incredibly exposed.”

Lawyers also caution about trusting that other frequently cited embargo exceptions such as activities “in support of the Cuban people” would provide cover for these online businesses.

For one, the “support-for-the-Cuban-people category primarily refers to travel to Cuba; it’s not a broad license,” says Robert Muse, a lawyer and Cuba expert who has opposed the U.S. embargo.

“Just because you’re claiming you’re doing God’s work in Cuba, that doesn’t immunize you,” Muse said. “We do exist under the embargo, unfortunately.”

Private businesses linked to the Cuban government

The increased attention over these online stores comes amid concerns shared by some Cuban activists and exiles that the Biden administration’s policies to support the private sector in Cuba could be exploited by the Cuban government or those close to it.

For U.S. officials, e-commerce platforms play an essential role at a time when food shortages in Cuba have worsened.

“The Cuban people are facing a dire economic and food security situation,” a spokesperson for the State Department said. “The United States has taken action to facilitate the delivery of private humanitarian donations and other agricultural and medical exports. Platforms permitting food purchases in the United States for delivery in Cuba connect the Cuban people with food supplies.”

A spokesperson for the Treasury Department stressed that the goal of the administration’s policies is to “encourage commercial opportunities outside of the state sector” by helping independent Cuban entrepreneurs access e-commerce platforms.

The spokesperson said the administration was also working to expand access to “additional payment options for Internet-based activities, support electronic payments, and facilitate business engagement with independent Cuban entrepreneurs.”

But activists worry that the Cuban government is adapting to benefit from those regulations. The story behind Tuaba products offered on both Cubamax and Supermarket 23 websites shows how this could be happening.

Under Raúl Castro’s command, Cuba’s Communist Party adopted a number of reforms to decentralize the economy, which were stalled for many years. But as the pandemic shut down tourism and the government became desperate for cash, some reforms gained pace, including transforming state companies into small and medium private enterprises.

The first step was to create local, small-scale state enterprises that were granted more freedoms than the typical state company. That’s how Tuaba was born, as the brand of Media Luna, a local mini-industry project by the state’s Empresa Integral Agropecuaria in Ciego de Ávila. Created in 2020, Media Luna started producing juices and guava bars, and it was so successful that it was featured on the Ministry of Economy’s website.

Then without further explanation, state media announced in October last year that Media Luna was now a “private medium enterprise,” the first one in Ciego de Ávila. In reality, not much had changed.

Despite its “non-state” status, the enterprise was committed to “the defense of the achievements of socialism,” one of its officials said during a Communist Party meeting attended by Cuban leader Miguel Díaz-Canel, Cuban state news agency ACN reported in March.

According to the ACN report, the company’s chief economic officer, Yamilka Avilés, said the enterprise got into e-commerce “with payments from abroad,” confirming Media Luna marketed goods “in several foreign platforms.” That activity generated $5 million in revenue in 2021, and $1.2 million was handed directly to the state’s central budget account, the report says. Another $108,000 and 4.5 million Cuban pesos were delivered to the local government.

García Bacallao, who filed the complaint with Florida’s attorney general, said U.S. officials might miss those connections.

“I think that now there is an urgency because the Cuban state is using this strategy around the private enterprises to give an idea of economic opening, of change,” García Bacallao said. “And the United States government is accepting that as something true.”