'Jaws' Revisited: The Truth About Shark Attacks

Facts You Can Sink Your Teeth Into

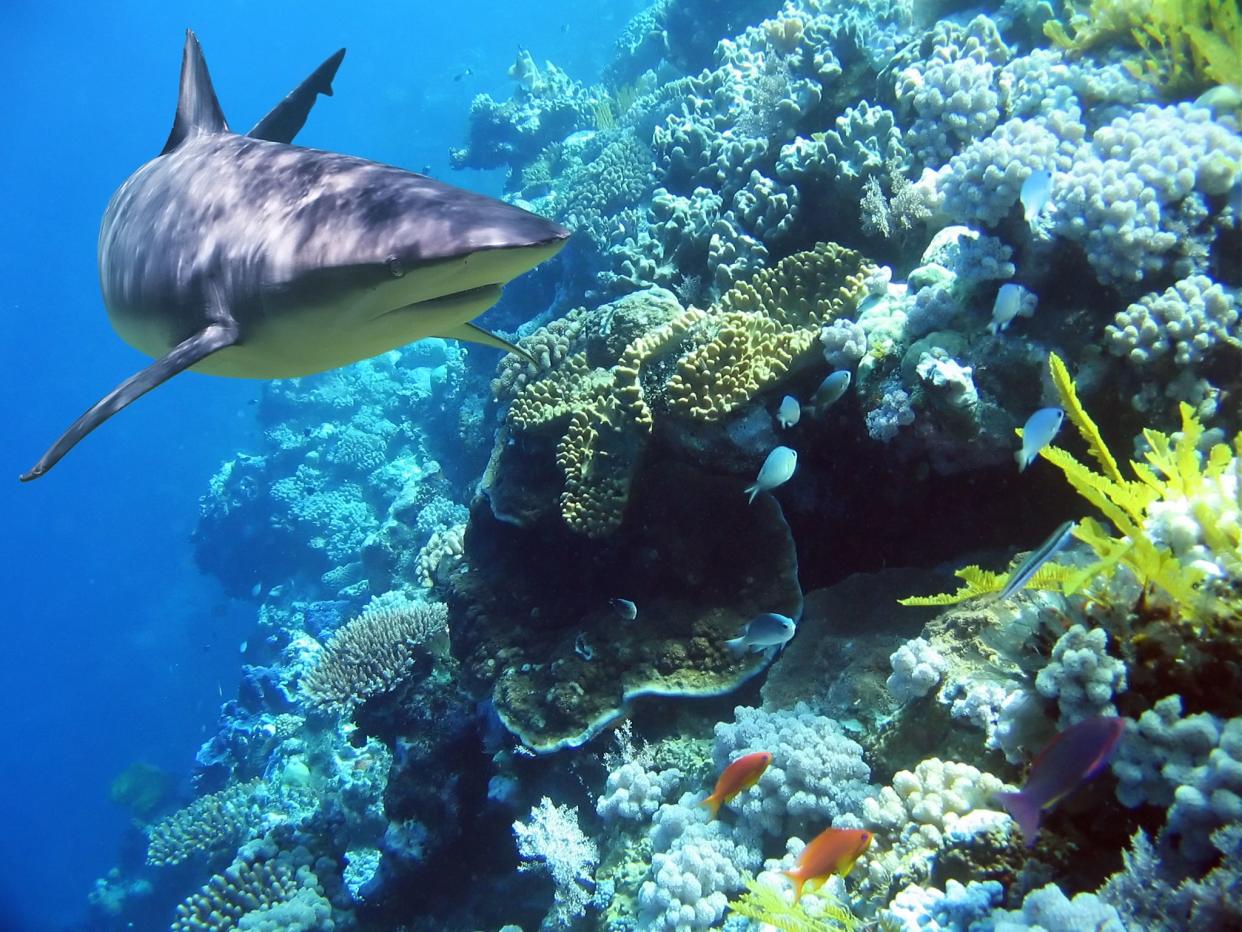

Few animals inspire the level of fear that sharks do, thanks to “Jaws” and other sensational tales of deadly encounters, and a steady stream of U.S. shark sightings has been the stuff of headlines this year. But these admittedly intimidating creatures get a bad rap. If you’re thinking of a break at the beach, here are some things to keep in mind about shark attacks, including, truth be told, just how unlikely they really are.

Related: Water Safety Tips That Could Save You From a Swimming Disaster

Your Risk Is Greatest Here in the U.S.

The United States leads the world in unprovoked shark bites, notching 41 cases in 2022, including one fatality, according to the University of Florida. That's 72% of the world's 57 total unprovoked bites, and represents a drop from the 47 unprovoked bites reported in the U.S. in 2021. Australia was a distant second with nine attacks in 2022, but no fatalities. Some 39% of the U.S. bites (16) occurred in Florida, followed by New York (eight), Hawaii (five, including one fatality), and California (four).

Unprovoked bites were down worldwide in 2022, declining about 22% — to 57 from 73 in 2021 — and they were also lower than the previous five-year average (2017-2021) of 70 such incidents. Time will tell what 2023 will bring, but there have been at least 58 so far this year, including eight fatalities.

Related: Surprising Facts About America’s Beaches

Still, Deadly Shark Attacks Are Rare

Petrified of sharks? Maybe this will help you keep the risk in perspective: According to the World Animal Foundation, the truth is, your chances of being killed by a shark are about 1 in 4.3 million. Compare that with your odds of being hit by lightning (1 in 79,746), drowning (1 in 1,134), dying in a car crash (1 in 84), or dying of heart disease (1 in 5), according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

They Aren’t Even the Deadliest Animal

In the grand scheme of things, mosquitos kill about 1 million people a year thanks to diseases such as malaria. Also way deadlier than sharks, according to CNET: snakes, dogs, scorpions, tapeworms, crocodiles, hippos, deer, jellyfish, bees, ants, horses … the list goes on.

Sharks Should Be Way More Afraid of Us

When it comes to whether humans are more deadly to sharks or sharks are more deadly to humans, in truth, there’s no contest. We kill an average of 100 million sharks a year, mostly in commercial fishing operations. Compare that with 10 fatal shark attacks against humans in 2020 (and even that was a big spike from the average of four per year).

Most Species Don’t Bite

Of 548 known shark species, only 13 have bitten humans in 10 or more confirmed incidents. The biggest threats are what the Florida Museum of Natural History calls the “big three”: white sharks, tiger sharks, and bull sharks.

Sharks Attack Mostly Men

Researchers at an Australian university found that 89% of unprovoked shark attacks between 1982 and 2011 involved men. Researchers say it’s unlikely that sharks inherently find something about the Y chromosome more irresistible, though. Instead, men are likely attacked more because they’re more likely to engage in activities that put them at risk, such as surfing and diving.

For more fun trivia stories, please sign up for our free newsletters.

Curiosity Might Be Behind Most Attacks

While conventional wisdom holds that sharks attack after confusing humans for prey, the more likely reasons are curiosity and confusion. Encyclopedia Britannica notes that sharks rarely bite more than once or twice even during fatal attacks. They may simply be “mouthing” an unfamiliar organism, or even defending their territory against what they think may be a rival hunter.

There Are Three Main Kinds of Shark Attacks

Researchers classify unprovoked attacks as hit-and-runs, sneak attacks, or bump-and-bites. Hit-and-run attacks, when a shark may mistakenly bite a swimmer in shallow water, then flee, are the least serious. Sneak attacks involve sharks attacking without warning in deeper water, while sharks in bump-and-bite attacks bump first, then attack.

Yes, They Can Smell Blood — But Not as Well as You Think

That whole “blood in the water” trope from shark movies is exaggerated. The sharks with the most sensitive sense of smell can detect smells at roughly 1 part per 10 billion, marine biologist Maddalena Bearzi tells Reader’s Digest. That may sound extreme, but that’s akin to a drop of blood in a swimming pool. In other words, a shark will still need to be fairly close to begin with to detect your minor cut. Still, experts advise against swimming with an open wound, and say women may even want to think twice during their period.

Sharks Eat Way More Than Meat ...

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, sharks will nosh on just about anything, whether that’s meat, plants, or … well, other stuff. Tires, a fur coat, and a full suit of armor are among the more curious finds from shark stomachs.

… And They’re Not Always Hungry

Despite their pop-culture portrayal as ravenous eating machines, sharks can and do go for quite awhile without food. Most can fast for up to six weeks, and researchers even documented one shark that didn’t eat for 15 months. Researchers with SeaWorld say sharks only eat anywhere between 1% and 10% of their bodyweight per week.

They May Be Attracted to Certain Colors

Because sharks can see high-contrast colors well, they’re more likely to be attracted to bright hues (and shark researchers have even been known to refer to “yum yum yellow”). On the flip side, low-contrast colors such as blue or black are less likely to catch a shark’s eye — but the risk, of course, is that it’s also much harder for human rescuers to spot those colors in the water.

Punching a Shark in the Nose? Probably a Bad Idea

Nearly everyone has been conditioned to think that a well-placed blow to a shark schnoz is the best way to fight an attack, but some experts disagree. For one, a shark’s eyes and gills are actually more sensitive than its nose. There’s also the pesky fact that punching a shark in the nose requires you to get pretty close to its mouth — generally not a good idea.

Sharks Don’t Actually Avoid Dolphins

While dolphins and sharks aren’t exactly best friends, swimming near a pod of friendly dolphins in no way means you’re safe from sharks. You’re actually likely to find sharks near dolphins because these carnivores often frequent the same hunting spots, according to LiveScience. And while dolphins occasionally do antagonize their toothy rivals, these incidents are few and far between.

A Single Shark Once Terrorized the Jersey Shore

A single great white shark attacked five victims, killing four, in the span of 12 days along the Jersey Shore in 1916. Some have speculated that the gruesome incidents even inspired Peter Benchley to write “Jaws,” (a claim he has since denied). In response, communities fenced their beaches and even offered rewards for fishermen to kill as many sharks as possible.

U.S. Sailors Endured History’s Worst Shark Attack

Talk about a nightmare: When a Japanese submarine sank a U.S. ship in 1945, almost 300 sailors died immediately, and about 900 others were left struggling to survive in the open water. The chaos and blood soon drew sharks who fed for days on both the living and the dead, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Ultimately, only about 300 sailors survived the ordeal. While many drowned or died of heat or thirst, anywhere from a few dozen to 150 may have been killed by the sharks.

The South African Government Once Tried to Bomb Sharks

Beginning in December 1957, seven people died and several others were injured in shark attacks off the coast of South Africa over the course of several weeks. In response, officials gave lifeguards rifles, built wooden barriers, and even dropped depth charges — essentially, underwater bombs — into the ocean. Unfortunately, the bombs simply managed to kill a bunch of fish and attract even more sharks, according to History Daily. Oops.

A Shark Attack Survivor Invented Cage Diving

Rodney Fox was spear-fishing off the Australian coast when a shark attacked him in 1963. He was left with a collapsed lung, ruptured spleen, broken ribs, and countless gashes, but survived. Instead of swearing off the ocean, he went on to study sharks intently, inventing cage diving and becoming a go-to expert, even helping Steven Spielberg obtain underwater footage for “Jaws.”

Australia May Have Had a Real ‘Sharknado’

If “Sharknado” taught us anything, it’s that sharks and tornadoes are just as enthralling a combination as snakes and planes. In 2017, Cyclone Debbie may have picked up a bull shark and deposited it in Ayr, Australia, which is several miles inland. Fortunately for the citizens of Ayr, instead of dozens of hungry great whites raining down on the city, there was just one very lonely, very dead shark deposited in a large puddle.