Before Trump and Johnson, Kansas tried a proof of citizenship voter law. It failed

Reality Check is a Star series holding those with power to account and shining a light on their decisions. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at RealityCheck@kcstar.com.

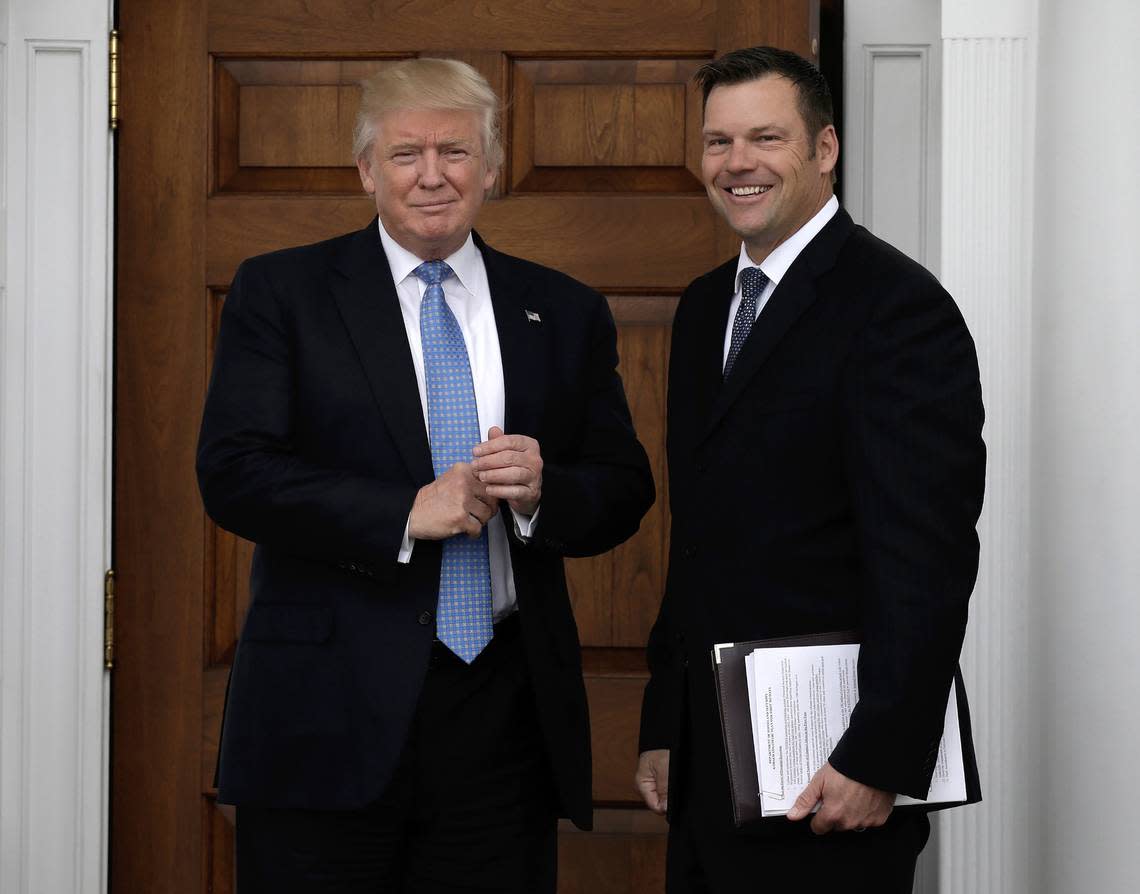

When Kris Kobach, then the Kansas secretary of state, met with Donald Trump shortly after the 2016 election, he brought along a plan that included changing a federal voter registration law to “promote proof-of-citizenship requirements.”

More than seven years later, Trump and House Speaker Mike Johnson want to go further.

At a Mar-a-Lago news conference last week, Trump, the former president running for a second term, looked on as Johnson condemned the lack of a federal requirement that individuals prove their citizenship to vote.

Non-citizens are already prohibited from voting in federal elections, but the speaker, a Louisiana Republican, echoed baseless concerns that large numbers of migrants are registering to vote in the run up to the 2024 election.

“We think that’s a serious problem. So what we’re going to do is the House Republicans are introducing a bill that will require proof of citizenship to vote. It seems like common sense,” Johnson said.

But proof of citizenship voter requirements aren’t a new idea. More than a decade ago, Kansas enacted its own law.

It imploded.

The Kansas Legislature passed a sweeping elections security bill in 2011. Along with requiring voters to show a photo ID at the polls, the measure mandated new voter registration applicants provide documentary proof of citizenship such as a birth certificate, U.S. passport or naturalization documents.

A U.S. district court judge and a federal appeals court both found the requirement unconstitutional and struck it down. Kobach, now the Kansas attorney general, championed the law as secretary of state and personally led a disastrous defense of it during a federal civil trial. The judge found him in contempt and ordered remedial legal education.

Kansas’ experience with its proof of citizenship law offers a window into the significant challenges any federal requirement would face. At the high-stakes 2018 bench trial, Kobach produced few examples of non-citizens who registered to vote – at most 67 non-citizens registered or attempted to register to vote over 19 years.

“One would hope that folks would follow the example, right, and figure out the natural conclusion of this which is that it is not legally tenable, it is not popular, it is not based on reality,” ACLU of Kansas director Micah Kubic said.

“But instead, they continue to follow what he explains about it and what his narrative is rather than the results.”

Congress almost certainly won’t pass a proof of citizenship law this year. Even if the House passes a bill, the measure would be dead on arrival in the Senate where Republicans are in the minority. President Joe Biden would be virtually guaranteed to veto it.

But Johnson’s decision to float the plan during a joint appearance with Trump suggests the idea could reemerge in a second Trump administration. If Trump emphasizes the issue, Republican-controlled state legislatures may decide to act.

And if Trump loses the election, Johnson and other Republicans have provided a groundwork to characterize the loss as fraudulent. Trump continues to assert falsely that the 2020 election was stolen and the proof of citizenship idea sets up migrants as a possible scapegoat for a second loss.

“You know what, if the numbers are so high, there are so many illegals in the country that if only one out of every 100 voted, they would cast potentially hundreds of thousands of votes in an election. That can turn an election,” Johnson said.

“This could be a tight election in our congressional races around the country. It could, if there’s enough votes, affect the presidential election.”

What Johnson’s comments left out is that states already take steps to enforce bans on non-citizen voting. Before and after Kansas’ proof of citizenship law, voter registration applicants must attest they are citizens under penalty of perjury.

U.S. District Court Judge Julie Robinson, who held the trial over the Kansas law, wrote in an opinion that the evidence supports the conclusion that “very few noncitizens in Kansas successfully registered to vote under an attestation regime.”

At the same time, the proof of citizenship law – sometimes called DPOC for documentary proof of citizenship – left thousands of residents who were unable to provide proof of citizenship on a “suspense list” and therefore unable to cast a ballot. More than 31,000 residents in total either had their voter registration applications suspended or canceled.

“In sum, we conclude that the DPOC requirement imposed a significant burden on the right to vote,” an opinion from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit said.

‘It just isn’t happening’

Johnson hasn’t released a proof of citizenship bill. During Friday’s announcement, he didn’t outline how citizens without easy access to documents would prove their citizenship – or what documents would be acceptable. He said the plan would require states to remove noncitizens from existing voter rolls.

In Kansas, residents without the necessary documents were allowed to appear before the State Election Board, where officials judged whether they were a citizen. The provision led to public hearings where residents made their case.

For instance, in one 2016 meeting a 75-year-old Osage County woman born in Arkansas recounted how she had lost her birth certificate and Arkansas couldn’t find a copy. The woman pointed to her presence in Census records, a record of her birth in a family Bible, baptismal records and documents about her high school attendance. The panel certified she was a citizen.

When the ACLU filed a lawsuit against the Kansas law in 2016, Donna Bucci decided to join. A 57-year-old Wichita resident at the time the lawsuit began, Bucci was placed on the suspense list and later purged from the state’s voter registration system after she was unable to provide proof of citizenship.

Bucci was born in Maryland, but didn’t have a copy of her birth certificate and Maryland’s $20 fee would have been a financial burden.

Speaking to The Star this week, Bucci said lawmakers need to “get out of kindergarten” and start working.

“Every time you turn around, they want to take someone else to court,” Bucci said. “If they spent as much time in the House doing what they’re supposed to be doing, we wouldn’t be going through all this BS.”

Josh Douglas, an elections law professor at the University of Kentucky, said a federal proof of citizenship law would encounter problems complying with the U.S. Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, which requires equal treatment under the law.

Still, he said the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts “has been extremely deferential to government laws on voting.”

The U.S. Supreme Court in recent years has shrunk the power of the federal government to protect voting rights by limiting the sweep of the federal Voting Rights Act. But it also rejected a request to review the appeals court decision striking down Kansas’ proof of citizenship law.

Mark Johnson, a Kansas City-based attorney who represented plaintiffs in one of two key lawsuits against the Kansas law, said he doesn’t believe Congress could pass a constitutional proof of citizenship law.

“Even before you get there the question is, is there a problem that this law would correct and there isn’t a problem,” Johnson said. “If there is a concern that non-citizens are voting, it just isn’t happening.”

Kobach told The Star that he supports Trump and Speaker Johnson seeking a federal proof of citizenship law. He said that if the U.S. Supreme Court had taken the Kansas case, it would have likely reversed the appeals court decision.

“The Kansas law can and should serve as a model for federal legislation,” Kobach said in a written response to questions provided by a spokesperson.

Kobach, who co-chaired Trump’s voter fraud commission, didn’t answer a question about whether he has advised Trump or the Trump 2024 campaign about election law.

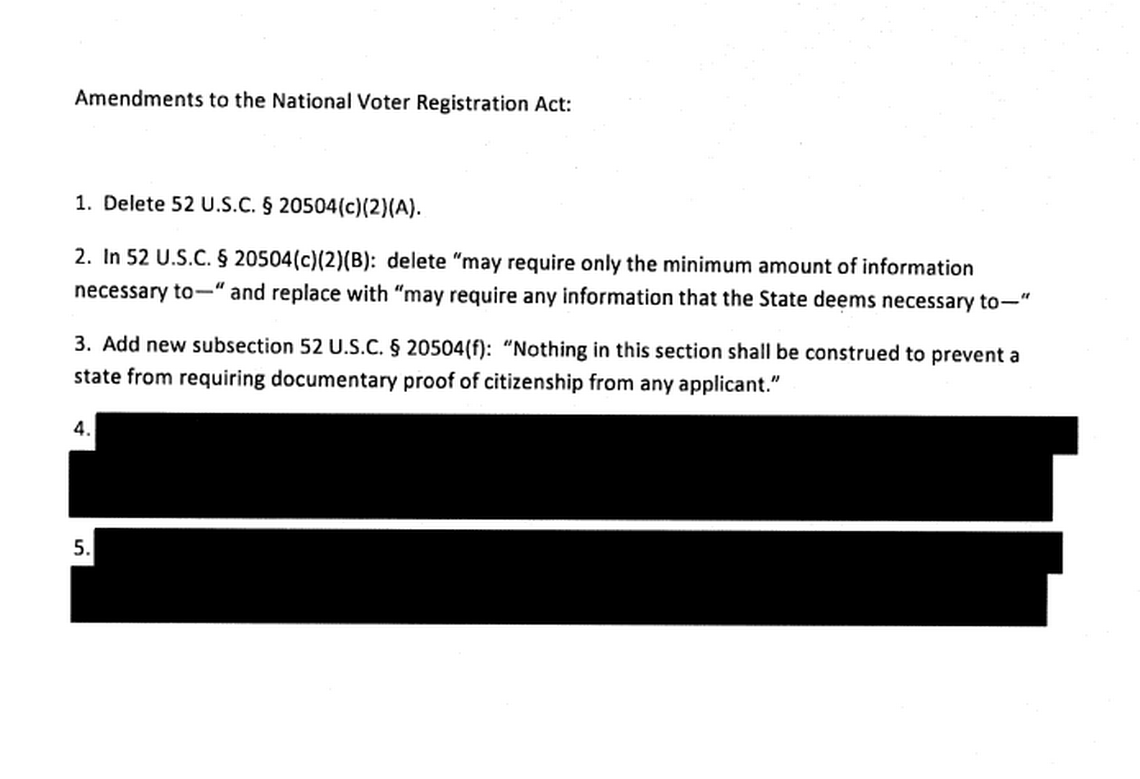

When Kobach met with Trump in the weeks following the 2016 election, he was photographed heading into the meeting with a partially visible plan for the Department of Homeland Security. Under a section titled “Stop Aliens from Voting,” the document read, “Draft Amendments to National Voter Registration Act to promote proof-of-citizenship requirements.”

The National Voter Registration Act – often called the motor voter law – requires states to offer residents the opportunity to register to vote at motor vehicle offices.

The ACLU later obtained another portion of Kobach’s plan, which outlines changing the NVRA to provide states leeway to impose their own proof-of-citizenship requirements. While Kobach’s November 2016 plan for Trump would have made it easier for states to adopt proof of citizenship rules, Johnson’s new plan would go further by mandating it at the federal level.

Will the House act?

Johnson’s appearance with Trump last Friday was seen as an important endorsement of the speaker by the former president at a moment when he faces a looming effort by lawmakers to remove him. But the proof of citizenship proposal itself hasn’t attracted as much attention inside the Capitol, which is consumed with the House’s efforts to pass foreign aid bills and the Senate’s impeachment trial of the Homeland Security secretary.

Rep. Ron Estes, a Wichita Republican, took a moment to realize which proposal The Star was referring to when asked about Johnson’s plan this week. He echoed concerns over states allowing non-citizens to vote (a small number of states allow non-citizens to vote in some local elections but federal law bans non-citizens from voting in federal elections).

“We’ve had a long history where states have the responsibility to actually conduct the voting itself. However, there is a federal definition of what it takes to elect federal office holders in all forms and to be seated here in Congress,” Estes said. “So that’s a purview we still have at the federal level.”

But some conservatives in the past have argued that states have sweeping power over who is qualified to vote.

In an amicus brief asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the challenge to Kansas’ proof of citizenship law, a coalition of GOP-leaning states said, “States have the exclusive constitutional authority to set voter qualifications.”

The 2020 brief, which was signed by Eric Schmitt, then the Republican Missouri attorney general and now a U.S. senator, said that “federal control over who may vote has come in the form of constitutional amendments, not statutes passed by Congress.”

Schmitt on Tuesday said there should be greater protections to ensure non-citizens aren’t voting. He said the Missouri General Assembly “is talking about putting that on the ballot, too” – a reference to a proposed state constitutional amendment that would make changing the state constitution more difficult.

One version of the proposal includes language prohibiting non-citizens from voting on state constitutional amendments, even though they currently aren’t allowed to cast ballots.

“When you’re talking about sort of threshold issues, non-citizens voting certainly rises to the level of, I think, us moving something,” Schmitt said.

Kubic, the ACLU of Kansas director, said supporters of proof of citizenship requirements were essentially attempting to have it both ways.

He noted the fierce opposition in Congress to H.B. 1. The Democratic bill, introduced in 2021, would require states to offer same-day voter registration for federal elections and included other election and campaign finance overhauls.

“What you can do is say the federal government should be guaranteeing and expanding the right to vote at every turn – that is a consistent position. But that is not their position,” Kubic said.

“Their position is instead whoever is going to be the most restrictive, whether the state or federal government, that’s the entity that should have the power at that moment.”