‘A triumphant return:’ Once shunned here, artist Charles Williams is back in major show.

“an extraterrestrial on your own planet, sentenced to wander the galaxy”

— excerpt from “Star Black for Charlie Williams” by Frank X. Walker

Charles Williams is coming home. Or perhaps it would be better to say he’s having a homecoming, a celebration, a triumph. It’s triumph, after all, to have your art — from comic strips to paintings to exuberant, cosmic sculptures — feted and acclaimed in Atlanta and Chicago before it even reaches your hometown. You might remember Williams from his house on Short Street — the painted trees, the rocket ships, the huge cut-outs of superheros. Maybe you saw him driving around in a big car in a big suit and beret, looking as friend Robert Morgan remembered him, “like a space pimp, smoking a pipe.” He was pointed out as one of Lexington’s eccentrics, but still ignored and unrecognized by most during his short life.

Lexington passed Williams by. But in death, Williams has returned as a serious, visionary artist, coming home with his own show in the main gallery of the University of Kentucky Art Museum.

“This show coming back here with such academic applause is really a triumphant return of Charlie’s spirit,” Morgan said. “I take great glee in him coming home this way.”

“The Life and Death of Charles Williams,” which will be up through November, will allow Lexington to meet one of their former townspeople, to understand his Kentucky life and the ways he reached beyond it. The title of the show is telling, at least it ought to be for us here. Williams lived an extravagant, exuberant, difficult and tragic life — he died of AIDS in 1998 at the age of 55, literally starving to death. But he inspired local AIDS activist Michael Thompson to create Moveable Feast, a nonprofit that delivers meals to Lexington residents with HIV and AIDS.

“His life and his work are so complex,” said Phillip March Jones, the founder of the Institute 193 gallery, a tireless advocate for Williams and curator of the new show. “Obviously in death he’s able to accomplish and communicate a lot more.”

The Martians Can’t Stay

Williams grew up in a segregated hollow of Blue Diamond, a coal mining company town outside Hazard into a family of Black coal miners. He was raised by his grandparents. In an interview before his death, Williams said he first got interested in art by making mud pies and watching them dry.

“Then I started figuring out how to draw by copying comic books. That would be about 1950. I did try to draw Captain Marvel and Superman. I did learn to draw the faces of Dick Tracy and Batman because they were square faces and easier to learn or draw. I picked them two because they were the easiest to draw because of the square chins. I had a bunch of things I used to get off into. I had no books on art or drawing, or knew of such even existed. I could draw better than I could write.”

His story moved on to Chicago, where his mother lived, to Morganfield, Ky., in the 1960s, where he joined the Breckinridge Job Corps Center to learn job skills, including working on the center’s newspaper, the Breckinridge Bugle. That’s when he created his first comics JC of the Job Corps, which appeared weekly. He went on to create more comics, “Cosmic Giggles,” a kind of Afrofuturist screed that shows a group of extraterrestials faced for the first time with so much racism, including a KKK rally, pollution, and other ills that they leave. He described it as “A COSMIC CARTOON COLLECTION OF EXTRATERRESTRIAL BEINGS VISITING THE EARTH, AND WITH THE POLLUTION PROBLEMS, GAS SHORTAGE, BAD WEATHER AND WITH THE RENT GOING UP, THE MARTIANS CAN’T AFFORT TO STAY THERE SO THERE WOUN’T BE ANY “WAR OF THE WORLDS” (sic).

Williams moved to Lexington and got a job as a janitor at the new IBM factory, where he started to collect left over pieces of plastic from the machines that made the computers. They melted and dried into bizarre shapes, which he would paint, glitterize, accessorize and drill holes into for a series of what are now called pencil holders, an accurate but staid description of the what Williams made of what he saw in executives offices.

Here’s how he described them: “I made a bunch of pencil holders, all sizes. That first one was from stuff some guys gave me at work. Plastic melts off the machine and it takes certain forms when it hits the floor. It becomes solid with weird shapes. I put them on a stand and paint it, keep it in its unique weird stage, and some of them forms looks like a animal’s brain. Makes you think of a brain.

“My drawings or sculptures are from ideas of things I do think of or about, not from some emotion feelings or anything of such. Though nothing is wrong with such. But my artwork is from things I see, think of, create, or all of the above.”

The show also has a series of large sculptures of salvaged and assembled materials of what Jones calls “vessels,” that convey knowledge, history, Black culture into the future. Williams may be known as an outsider or folk artist, but Jones thinks there is nothing instinctual or folksy about it.

“It’s deliberate and purposeful,” he said. “Charles was someone literally looking far out and looking to the cosmos for answer to the problems that plague the world. He was unafraid of any medium, scale or size.”

Souls Grown Deep

That we have anything left or know anything about Williams is largely thanks to Morgan and Jones and an Atlanta collector named Bill Arnett. Arnett had started collecting the work of Southern Black artists, including the famous quilts of Gee’s Bend, Ala. Eventually it became known as the Souls Grown Deep collection. At some point in the late 1980s, he was alerted to the work of an outsider artist in Lexington, and he started buying Williams’ work. Morgan remembers talking to Williams one day after he got on a Greyhound to go to Atlanta for an exhibit at the 1996 Olympics that featured several of his pieces.

“He was celebrated in Atlanta, and then came back here to abject poverty,” Morgan said, and a body that was starting to feel the ravages of AIDS.

Williams died alone, except for the visits of Morgan, Thompson and some social workers. Morgan knew everything in the house and outside it would be thrown out. So he persuaded a social worker to let him in, and took several truckloads of Williams’ art and papers to the Kentucky Folk Art Museum in Morehead. Not long after, the house was demolished.

Much later, Jones, who grew up in Lexington, ended up as director of the Souls Grown Deep collection in Atlanta, and noticed the strange and compelling work of a fellow Lexingtonian. He and Morgan went through all the art that Morgan had deposited in Morehead and pieced together many of the comics that sat in boxes, and the sculptures from Arnett and the Folk Art Museum. In 2010, Jones put together a show at Institute 193 and Land of Tomorrow that first showed Charles Williams to his town.

Look at me

Jones had always wanted to do a larger showcase of Williams, and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center agreed to do the show. Then it traveled to Chicago to Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.

Bringing it to UK was an obvious win, said Stuart Horodner, director of the UK Art Museum.

“I knew the story of Charles Williams, which is extremely poignant,” Horodner said. “Charles Williams never had a major show in the place where he lived and worked, so this felt like an unbelievable opportunity to give the person what they never had in their lifetime. If Charles Williams was going to have had a show, it was destined to be here.”

Horodner hopes to do some programming with other departments in the fall around the show.

“How do we feel about marginalized or self-taught artist or those who become well-known only through supporters who are white?” he asked. “How do we navigate around potential mine fields around these issues. It’s a joy to see the work, but there are also questions about categorizations. This is also a great opportunity of putting Williams into the history of assembled sculpture.”

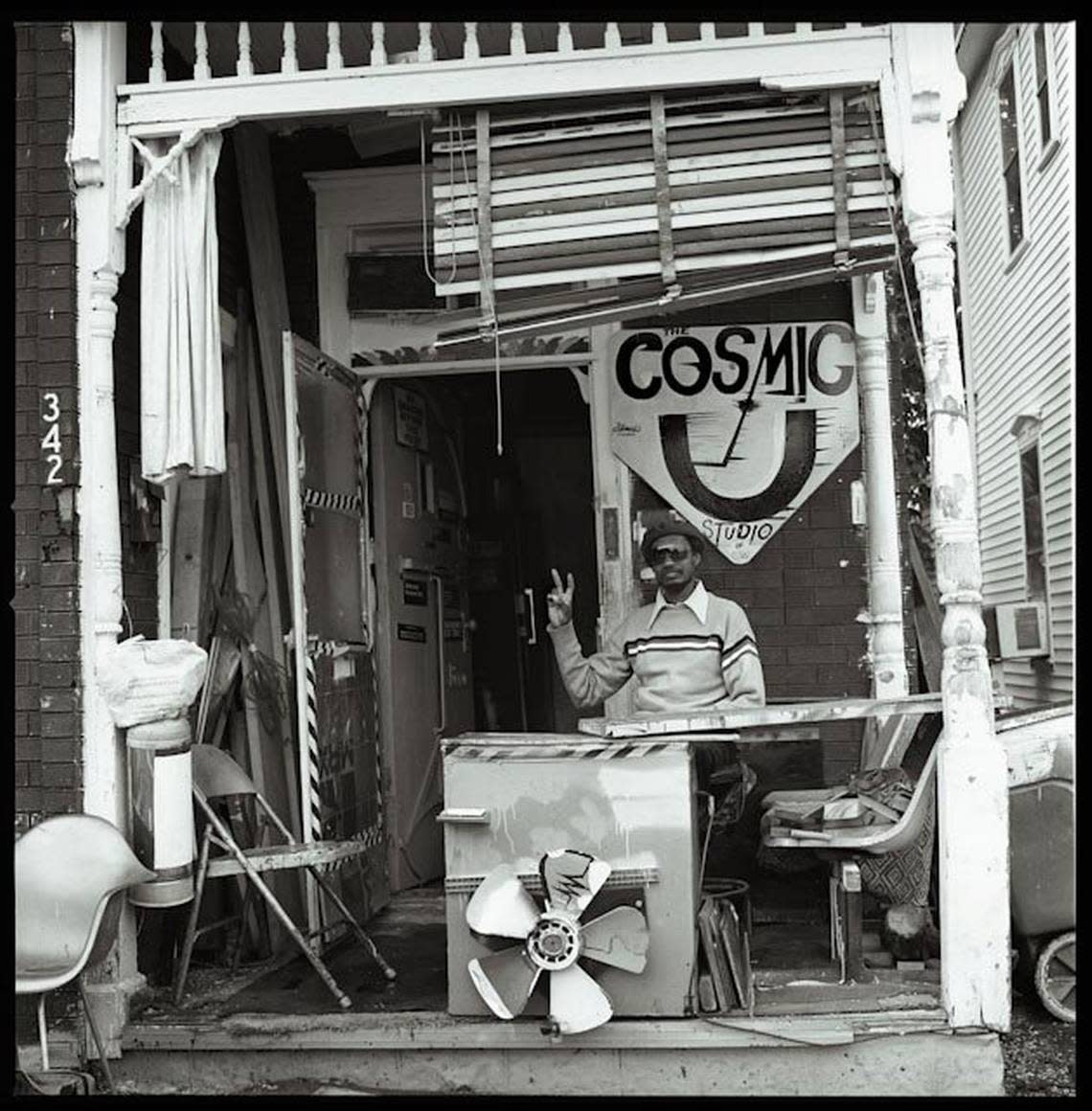

On July 22, the museum will hold an opening party for the show at the museum to reintroduce Williams to his former neighbors. Morgan and Jones also hope the show might fill in some of the narrative holes around the life and death of Charles Williams, perhaps from people who knew him when he lived in Lexington. As a Black queer artist, where did he fit in Lexington’s Black community, if at all? There’s the possibility of an oral history from people like photographer Melissa Watt, who took a series of photographs of Williams at his house for ACE magazine that are some of the only images of him left.

“He was showing me how he wanted to be seen,” Watt said. “He had a self assurance, he also seemed very mercurial and I felt some anger. I felt like he had been hurt. He seemed to value that I was there doing pictures with a real camera.

Williams wouldn’t let Watt in the house, but he showed her all around the yard.

“He wasn’t forceful,” she said, “but I think having the art in his yard was his way of saying, ‘look at this, look at me.’”

An opening reception for The Life and Death of Charles Williams will be held on July 22 from 6:30-8 pm at the UK Art Museum. The show, which will run through November is free and open to the public.