If the Triangle commuter rail is built in stages, which section should come first?

The complexity and high cost of building a commuter rail line in Durham mean the first leg of the Triangle’s regional transit project would largely be built in Wake County.

There’s not enough money to build the proposed $3.2 billion 43-mile commuter rail line all at once. So GoTriangle has suggested building it in phases and is asking the public to weigh in on which section should be built first.

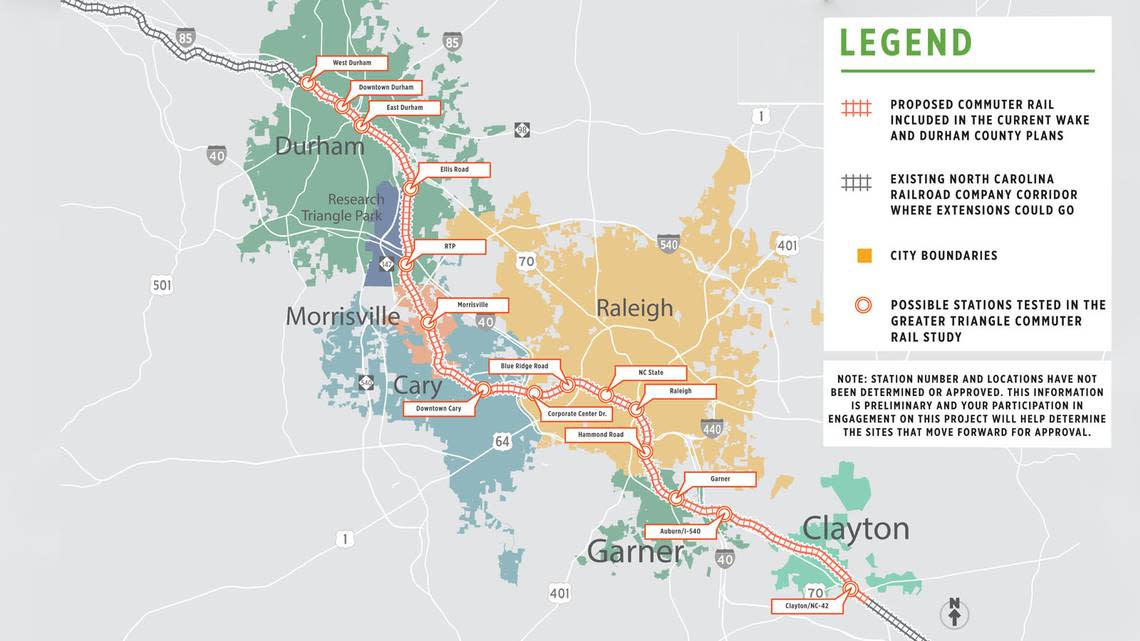

Commuter trains would use a new set of tracks built in an existing North Carolina Railroad Company corridor between West Durham and Clayton. Trains would stop at 15 stations, including Research Triangle Park and the Amtrak stations in downtown Durham, Cary and Raleigh.

GoTriangle’s feasibility study for the project breaks the line down into three sections: the western leg through Durham to Ellis Road or RTP; the middle from RTP to downtown Raleigh; and the eastern leg from Raleigh to either Garner or Clayton.

A survey published with the plan says the Durham leg is “being considered for a later implementation stage” and asks people to say whether they think construction should begin with the middle or eastern legs. The first leg would likely take a decade to build and be ready for passengers by 2035, according to the study.

The eastern section would be the easiest and cheapest to build, but starting in the middle makes the most sense, said Charles Lattuca, GoTriangle’s president and CEO.

The central part covers about half of the corridor for about a third of the entire system’s cost, Lattuca said. It would connect downtown Raleigh, N.C. State University, Cary and Morrisville and either RTP or Ellis Road in Durham for somewhere between $800 million and $1 billion.

It also gets GoTriangle closer to its ultimate goal of serving the Triangle’s two largest cities, Lattuca said.

“I really think the Durham and Raleigh connection is of the highest importance,” he said.

Durham leaders agree, which is why they’re hoping to avoid building the western leg later than the others. Durham endured years of planning for a proposed light rail line between the city and Chapel Hill that failed in 2019, in part because Duke University and the N.C. Railroad balked at providing needed right-of-way.

Durham deserves to be served by commuter rail as soon as possible, says Brenda Howerton, head of the county commissioners and a member of GoTriangle’s board.

“I’m not in agreement with building that last, no. It’s a bad idea,” Howerton said. “We need to do more now to find out what else is possible.”

The western leg is the most difficult and expensive because the second track would require more work on crossings, bridges and sidings, including around a Norfolk Southern freight yard in East Durham. The western section would cost $1.4 billion to $1.6 billion and take a dozen years to complete, according to GoTriangle.

At that cost, commuter rail would deplete the money generated by transit taxes in Durham. Waiting would allow Durham to build up more reserves and help GoTriangle make a better case for federal funding in the future, Lattuca said.

“If you can’t afford the whole project, the phased approach is a good approach,” he said. “I think if we start building something, it’s going to make us even more successful for federal grants in the future.”

Triangle’s third attempt to build a rail transit line

As the name implies, commuter rail was primarily conceived as a way to give people an alternative to driving to work. Highways have grown more congested as the region’s economy hums and attracts new companies and residents. More than 2 million people live in the nine-county Triangle region, and the population is expected to grow by a million more by 2050, according to the N.C. Office of State Budget and Management.

The commuter rail proposal is the third attempt to develop a regional transit line that runs on rails. In addition to the failed Durham-Orange Light Rail project, GoTriangle’s predecessor, the Triangle Transit Authority, spent years planning a similar commuter rail system along the N.C. Railroad corridor before the idea was abandoned in 2006 after failing to win federal support or funding.

Not everyone feels commuter rail is right for the Triangle even now. Aidil Ortiz, a long-time transit advocate who lives in East Durham, said the system seems designed not for people who use transit now but in hopes of luring people who don’t.

“We’re spending all this energy on the dreams of people who are not currently public transit enthusiasts anyway,” Ortiz said. “It feels like, ‘Oh, well big cities should have it. Progressive cities should have it.’ But are you, the people who are most professing it, already committed to the transit we have?”

People who rely on transit now in Durham would much rather see more frequent buses that serve a larger area, Ortiz said.

“They do not have a choice, in many instances, about their transit options,” she said. “They do not have the resources to get a car, so they are dependent on this public good. And what they have been telling us loud and clear is that they want improved bus service.”

Lattuca agrees that Durham needs more and better bus service, which is why it makes sense to delay building commuter rail in the county and not deplete its transit money. He said commuter rail would be one component of a successful transit system in the Triangle, in addition to buses and the planned bus rapid transit lines in Chapel Hill and Raleigh.

No one has committed to the commuter rail line yet. The feasibility study and the public feedback it receives are meant to help local and county officials in Wake, Durham and possibly Johnston counties decide whether to move forward.

Not building the commuter rail is an option, Lattuca said.

“Or they might just say, ‘You know what, this is just too expensive, go try and do something else,’” he said. “I don’t expect that’s going to be the case here, mostly because of the fact that we’re not creating something completely new. We have a corridor here that provides us an opportunity for transit, and the corridor is not going away. So I think the fact that we need to exploit this corridor, maximize its transit benefits, I think everybody agrees that’s a good idea.”

How to learn more, have your say

GoTriangle’s commuter rail feasibility study can be found at www.readyforrailnc.com/feasibility/. There’s a link on the page to the survey, which more than 3,200 people have completed so far. The agency will collect comments through Feb. 19.

GoTriangle is also planning a series of public open houses, where it will answer questions about commuter rail and accept feedback. Here are the events scheduled so far:

▪ Wednesday, Jan. 18. John Chavis Community Center, 505 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Raleigh. 6:30 to 8:30 p.m.

▪ Monday, Jan. 30. Durham County Public Library, 300 N. Roxboro St., Durham. 5:30 to 7:30 p.m.

▪ Monday, Feb. 6. Morrisville Town Council Chambers, 100 Town Hall Drive. 5:30 to 7:30 p.m.

▪ Tuesday, Feb. 7. Clayton Town Hall, 111 E. Second St. 5 to 8 p.m.

▪ Wednesday, Feb. 8. St. Joseph’s AME Church, 2521 Fayetteville St., Durham. 5:30 to 7:30 p.m.