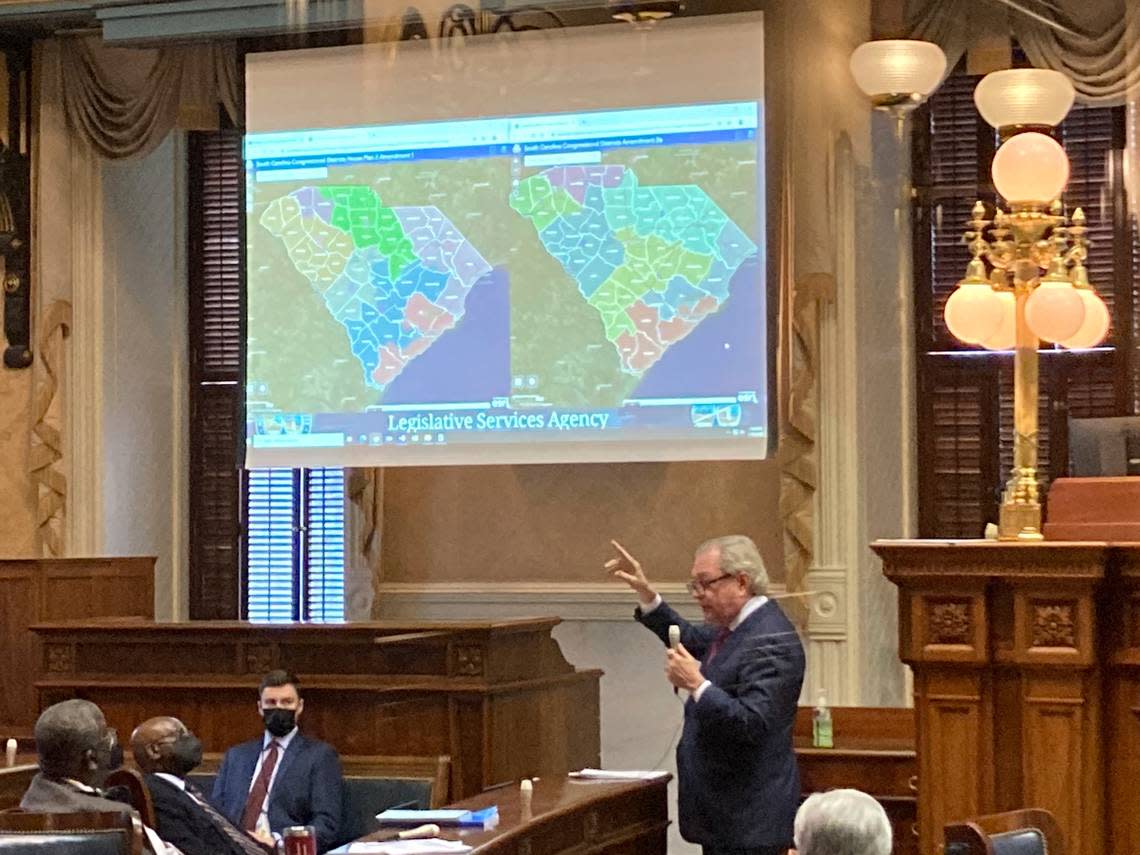

Trial set to begin over whether SC congressional map is ‘racially discriminatory’

Lawyers for the South Carolina chapter of the NAACP will argue in court this week that the state’s new congressional map discriminates against Black voters and must be redrawn.

A trial over the map, which the General Assembly passed in January over the objection of Democrats and good government groups, gets underway Monday at the federal courthouse in Charleston.

At issue is whether the map violates the 14th and 15th amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which granted all citizens equal protection under the law and gave Black men the right to vote.

The South Carolina NAACP filed suit in February charging that the new congressional map — which is expected to solidify the GOP’s 6-1 advantage in the U.S. House for the next decade — was unconstitutional because it diluted the voting strength of Black South Carolinians.

The plaintiffs, who are represented by several civil rights groups, including the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union, claim state lawmakers used race as the primary factor in drawing the 1st, 2nd and 5th congressional districts.

South Carolina House and Senate Republican leaders and the State Election Commission’s director and commissioners, who are named as defendants in the lawsuit, have denied that race factored prominently into the map’s construction.

A three-judge panel of Mary Geiger Lewis, Toby Heytens and Richard Gergel will hear arguments in the case over the next two weeks before rendering a decision on the map’s constitutionality. There is no deadline by which the judges must decide the case, although it won’t happen before Oct. 28, when post-trial briefings are due.

Regardless of the panel’s decision, the challenged map will be used in this year’s general election.

What to expect

The plaintiffs challenging the map make two broad claims in their suit: that race was the primary factor lawmakers considered when drawing congressional district lines, and that their use of race was motivated by intentional discrimination.

They need prove only one of the claims for the court to require that the map be redrawn.

Based on their complaint, the plaintiffs are likely to argue that lawmakers’ revision of the map to account for population shifts and growth over the past decade — primarily in Congressional Districts 1 and 6, represented by Republican Rep. Nancy Mace and Democratic House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, respectively — amounts to racial gerrymandering.

The new map significantly reduced the percentage of Black voters in Clyburn’s district — albeit not enough to eliminate their considerable say in the candidate elected — but did not reapportion the other six districts in a way that provided Black voters any real influence, they argued.

Rather than moving Black voters from the 6th into another district where they could have an electoral impact, the suit claims the new map dilutes their voting strength by spreading them across multiple districts to ensure that no other district has enough Black voters to elect their preferred candidates.

“Black and white voters were sorted among the congressional districts under the guise of correcting for CD 1’s significant overpopulation and CD 6’s underpopulation,” the suit argues. “But various alternatives were proposed to the Legislature which reapportioned South Carolina’s congressional map without locking in the majority’s advantage in six of the seven congressional districts and harming Black voters to achieve that objective.”

If the panel of judges finds the General Assembly prioritized racial considerations above all else, the House and Senate defendants would then need to make the case that their use of race to draw the maps was “narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest.”

The defendants already have said, however, that race was not a primary consideration when drawing the map.

Rather, defendants argued in their motion for summary judgment that the General Assembly had been engaged in a “legitimate political objective” when it drew the maps in a way that preserved and strengthened the 6-1 Republican advantage.

Politics, not racial antipathy, drove mapmaking decisions, they argued.

“District 1 had become ‘basically a swing district,’ having narrowly elected Democrat Joe Cunnigham in 2018 and Republican Nancy Mace in 2020, which prompted concerns (including from Mace herself) that Republicans could lose the district in future elections,” the defendants argued in their unsuccessful motion for summary judgment. “Based on these ‘political numbers,’ the General Assembly selected a map that equalized population while moving District 1 ‘to the Republican side.’”

While the argument that political considerations largely informed lawmakers’ mapmaking decisions contradicts what some members said during the redistricting process, it does not pose a legal problem for the defendants because the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 decided that partisan redistricting was a political question not reviewable by federal courts.

SC House map adjusted via settlement

In addition to challenging the constitutionality of South Carolina’s congressional map, the NAACP’s lawsuit also alleged the new state House map discriminated against Black voters.

The parties resolved that dispute prior to trial, however, with House Republican leaders agreeing earlier this year to adjust the map’s boundaries in three parts of the state — Richland/Kershaw, Orangeburg and Dillon/Horry counties.

The changes, which the Legislature approved in June and the governor signed into law, affect the boundaries of roughly a dozen districts in those areas and make material changes to a handful of districts.

In a statement released at the time, Brenda Murphy, the president of the South Carolina NAACP, called the settlement “a historic occasion.”

“Our political leadership has listened to our grievances and is working to create a more equitable political landscape,” Murphy said.

Attorney Mark Moore, who represents the South Carolina House in the lawsuit, said the settlement was “reasonable for voters” and should instill confidence in the electoral process.

“Certainty in our voting process is one of the greatest virtues we have in South Carolina — and trust in that process is of crucial importance to our people,” Moore said in a statement released at the time. “With this settlement, we will end costly litigation with a decision that is reasonable for voters and allows voters to have confidence in the electoral process.”

The adjustments to the state House map go into effect in 2024.