Who took $105,000 from security expert's Iowa account? Months later, he still doesn't know

Sam DeKay was enjoying a calm fall morning in his Manhattan apartment when an email came through.

First Whitney Bank & Trust in his hometown of Atlantic, Iowa, informed him that $9,950 had been debited from his account.

“Thank you for your business!” read the email, sent at 8:29 a.m. Oct. 10.

But DeKay, 75, said he had not made any payments or cut any checks from the account, which he inherited from his mother when she died in February 2023. Confused, DeKay called the bank, where employees pulled up a scan of a cashier’s check that had been deposited by an April McGilvra.

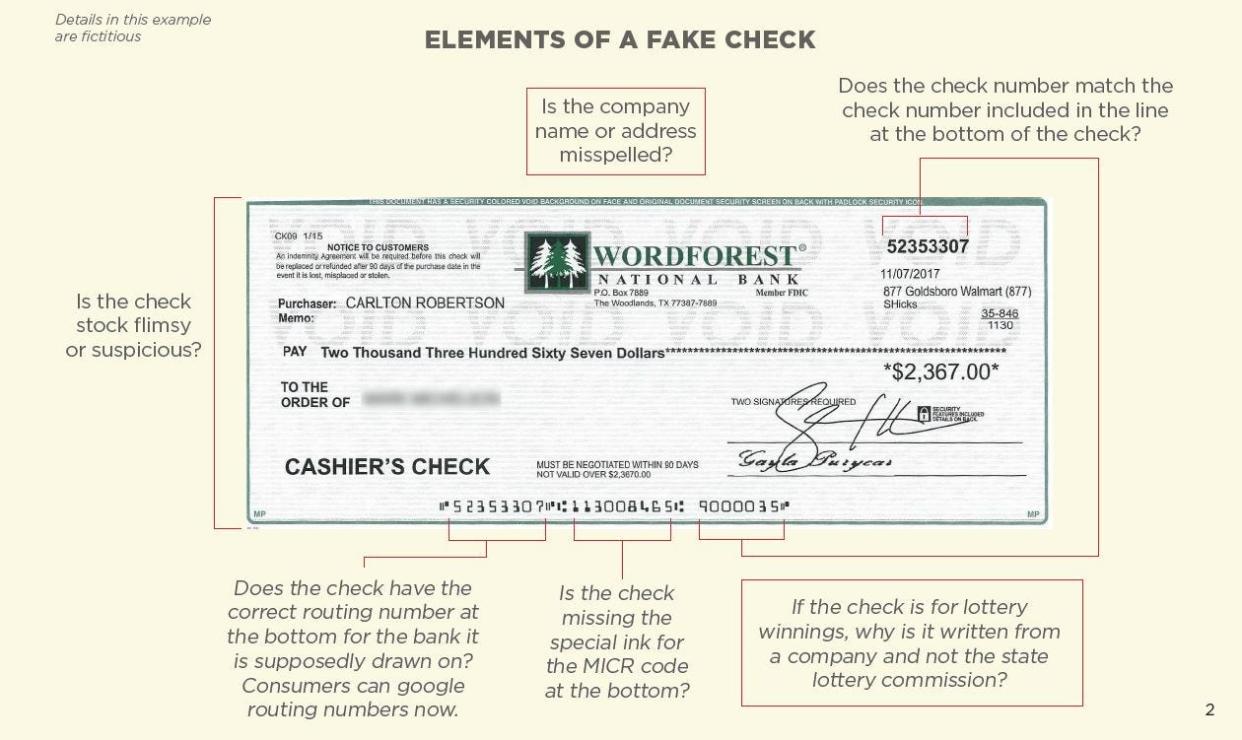

The check had DeKay’s account number at the bottom. At the top, it read “Whitney Bank and Trust” ― an incorrect name for the bank.

DeKay said that employees told him

someone must have committed fraud.

It was the beginning of a mystery that points to what experts say is a growing problem.

More messages, more missing money, more questions

The next morning, DeKay received two more emails from the bank.

“Thank you for your business!” read the first, informing him at 8:39 a.m. that his account had been debited for $50,500.

“Thank you for your business!” read the other one, sent at the same time, informing him that he was out another $45,250.

More: Iowa Attorney General fielded 3,700 consumer complaints in 2023. See the top categories.

Scans of two more checks, deposited by someone identified as Alan Cortez, looked almost identical to the first, with the same incorrect name for the bank.

DeKay said First Whitney has replaced the $105,000 that he lost. Still, four months later, the case perplexes him.

Of all people, DeKay has a particular interest in crimes like these. He spent his career protecting companies from fraud, retiring as vice president of information security at the BNY Mellon international investment firm.

“It becomes more of a detective story,” he said, “more of a forensic tale.”

Iowa check fraud cases more than doubled since the COVID-19 pandemic

DeKay’s story is not one of a victim taking justice into his own hands, tapping his decades of experience to track a criminal and extracting revenge.

Rather, DeKay reported the fraud to the Iowa Division of Banking. He said First Whitney employees told him they also would investigate the case. From his apartment overlooking the Hudson River, he recently told the Des Moines Register he doesn’t know what came of the case.

The Division of Banking has not contacted him since October, and a spokesperson for the agency told the Register that state laws ban employees from publicly disclosing details of investigations. First Whitney CEO Paul Gude, likewise, declined to comment on the details of DeKay's case.

More: Tens of thousands of dollars stolen from northwest Iowa banks in suspected check fraud scam

“Our staff continues to try and educate our customers and we have been able to stop a wide variety of scams from phishing to bogus phone calls seeking personal information,” he said in an email. “The thieves are innovative.”

Spokespeople at the Atlantic Police Department, the Cass County Sheriff’s Office and the Cass County Attorney’s Office said they had not received a report of check fraud at First Whitney. Asked why he didn’t report the case to law enforcement there, DeKay said, “The issues seem too technical for the Atlantic police.”

From his career in banking, DeKay said, he was surprised by the nature of the crime. He has long contemplated cyberattacks, with hackers extracting hundreds of thousands of dollars without fingerprints.

“This was an old-fashioned sort of fraud,” he said.

But the old-fashioned is back in vogue, banking experts say. Check fraud cases more than doubled in Iowa from 2020 to 2023, according to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a division of the U.S. Treasury.

Banks across the country have experienced a similar trend.

Banking and criminal justice officials say they aren’t quite sure why check fraud became more frequent since the pandemic. But Julie Gliha, vice president of regulatory compliance at the Iowa Bankers Association, said criminals returned their focus to checks after companies and regulators took steps to protect debit and credit card transactions.

“If they can get just a few checks through the system, they most likely can make a lot more money than several smaller debit card transactions,” Gilha said in an email.

Fraudsters 'wash,' 'cook' checks, use 'mules,' 'walkers' to carry out fraud

Paul Benda, the vice president of risk, fraud and cybersecurity at the American Bankers Association, told a Senate committee on Feb. 1 that criminals are stealing checks from the U.S. Postal Service. He said fraudsters have stolen master keys and taken several people’s mail in bulk. Some have assaulted mail carriers.

“The mail system isn’t nearly as secure as we thought,” Benda said.

Postal Inspection Service spokesperson Michael Marke told the New York Times in March that the Postal Service is trying to make its blue mail boxes more secure. Among other fixes, the department will add “rakes” with metal teeth to prevent thieves from reaching into the boxes.

More: Iowa prosecutions for fraud, forgery decline, but problems persist: How to protect yourself

Mike Burke, a senior robbery and crisis management consultant at Waukee-based payment processor Shazam, said encrypted messaging services like Telegram have helped criminals organize wide-scale check fraud.

He said fraudsters “wash” checks by using chemicals like nail polish remover to strip away pen ink. They can then write a new dollar amount and payee.

Alternatively, some fraudsters also “cook” checks by designing them online and printing them on check cardstock they obtain from other countries.

Once they have the checks, criminals can seek “money mules” or “walkers” in online forums. They are willing to cash the checks at banks, often with fake IDs.

“It’s exploded,” Burke said. “I’ve been in the game for 30 years, and this is the worst I’ve seen it.”

Big banks don't help small banks uncover fraud, says trade group leader

Thus far, DeKay said, he has been unsatisfied with First Whitney’s response to the case. He said employees have declined to explain how someone could have received fake cashier’s checks with his bank account number on them.

“They don’t want to talk about that,” he said. “They really don’t. The discussion always will suddenly turn into, ‘Well, we think maybe a hacker has gained access to your computer.’ Or, ‘I think you ought to change your password.’ It always comes back to (DeKay and his wife), as if we’re somehow responsible.”

He added that he struggles to understand how the problem could have occurred because of his online password. Before he retired, he said he helped BNY Mellon write policies on how employees could protect the company from hackers, authoring rules about password requirements, encryption, wireless communication and how employees should handle printed banking material.

First Whitney may also not know how the fraud occurred. David Caris, the CEO of Community Bankers of Iowa, a trade group, said small banks struggle to get information when criminals deposit checks at larger institutions.

“The smaller community banks tend to work harder to try and catch the criminal and find out how the fraud occurred and stop it than a lot of the big, national banks (do),” he said. “(Big banks) kind of just budget for it.”

DeKay said his inheritance of the First Whitney account followed the death of his mother, Elizabeth, in February 2023. He planned to transfer the funds to another account, but he had not gotten around to it by last fall. The bank closed his account and give him a new one after the fraud.

At the beginning of February this year, he said, a First Whitney employee called him to say the bank detected another fraud attempt. This time, he said, someone tried to wire money out of his account. He said the bank caught it, shut down his account and gave him a new one ― his third account in four months.

He said he has transferred all but $10,00 out of the First Whitney account.

“There was kind of a hometown pride to it,” he said of holding on to the account. “Now, of course, that’s very much gone.”

How not to be a check fraud victim

Sarah Grano, spokesperson for the American Banking Association, provides this information about check fraud and how to avoid it.

Consumer tips (https://www.aba.com/advocacy/community-programs/consumer-resources/protect-your-money/check-theft-and-check-washing)

What is check washing and how is it used?

Criminals steal paper checks sent through the mail, for example, by fishing them from U.S. Postal Service mailboxes or by taking them out of your personal mailbox. They may even rob postal workers in search of checks. Once they have a check you wrote and mailed, for example, to a charity, they use chemicals to “wash” the check in order to change the amount or make themselves the payee. They then deposit your check and steal money from your account. If you have mailed a check that was paid, but the recipient never received it, you may be a check washing victim.

How can you protect yourself?

Consider making payments using e-check, ACH automatic payments and other electronic and/or mobile payments.

Use pens with indelible black ink so it is more difficult to wash your checks.

Follow up with charities and other businesses to make sure they received your check.

Use online banking to review copies of your checks to ensure they were not altered.

If you still receive paid checks back from the bank, shred ― don’t just trash ― them.

Regularly review your bank activity and statements for errors.

Don’t leave blank spaces in the payee or amount lines of checks you write.

The U.S. Postal Inspection Services also recommends that you:

Drop off mail in blue collection boxes before the last scheduled pick-up time or directly at your local post office.

Regularly check your mail. Do not leave your mail in your mailbox overnight.

If you’re heading out of town, have the post office hold your mail or ask a trusted friend or neighbor to pick up your mail.

What to do if you’re a victim? File a report immediately with:

The United States Postal Inspection Service at uspis.gov/report or call 1-877-876-2455.

Your local police department .

Your financial institution .

Tyler Jett is an investigative reporter for the Des Moines Register. Reach him at tjett@registermedia.com, 515-284-8215, or on Twitter at @LetsJett. He also accepts encrypted messages at tjett@proton.me.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: As check fraud rises, Iowa couple reports $105,000 theft