A toast to Harrelson Hall, Catalano House and other lost landmarks of Raleigh character

I couldn’t swear it’s true, but somebody once told me that Asheville and Wilmington kept their most charming and historic buildings intact because they couldn’t afford to knock them down.

But Raleigh, with state government as built-in industry, could always spare a dollar for the wrecking ball.

As our city approaches half a million souls, the picturesque relics I cherish around Raleigh grow increasingly scarce, with the tube-shaped Holiday Inn downtown and the Char-Grill with its crinkle-fry roof on Hillsborough Street facing their final days.

Some people like the boxy canyon Hillsborough Street has become, and some aren’t at all worried that New Bern Avenue is about to get the same treatment.

But on this Monday of nostalgia, without any finger-pointing or agenda, I offer this tribute to my favorites among Raleigh’s toppled treasures and the character we once possessed.

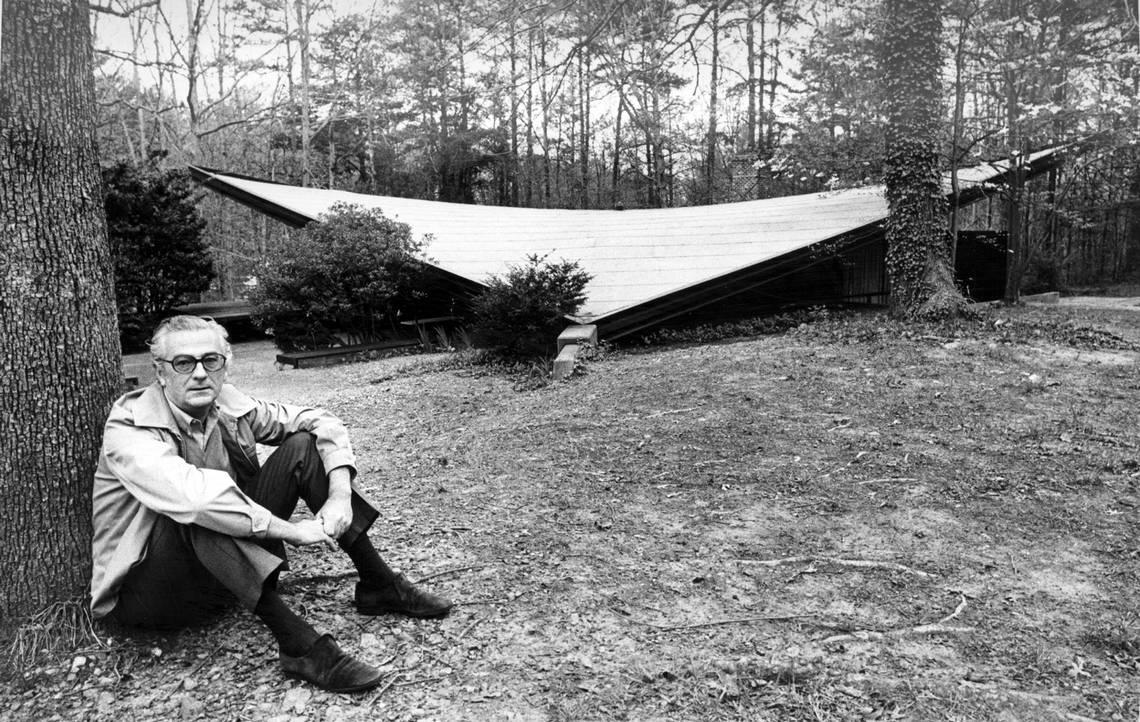

The Catalano House

In his own N&O list, architecture writer Michael Welton described this wing-shaped residence as both a “hypberbolic-paraboloid” and a “geometric gem.”

It garnered enough chatter in architecture circles to get talked about in London or Paris, bold and innovative enough to get a letter of praise from Frank Lloyd Wright. But some less-enthusiastic viewers compared it to a potato chip.

Eduardo Catalano built it for himself in 1954 while teaching at N.C. State School of Design, but when he later left for M.I.T. shortly afterward, it got passed around several owners, got abandoned and was razed in 2001, lasting not even 50 years.

But its street off Ridge Road — once Caminos Drive, now Catalano — bears his name.

The Fabius Briggs House

In its century on Hillsborough Street, the Briggs mansion housed Fabius Briggs from the prominent hardware family, the widow of Gov. Charles Aycock and an establishment of ill-repute.

In its later decades, Bourbon Street billiards stood out front, and later Jackpot, named “college bar of the week” by Playboy magazine.

Tall and chartreuse, it stuck out like a leisure suit on a rack of tuxedos. But despite multiple attempts to save the lovable curio, it had grown into a nuisance in the neighborhood, covered in graffiti and seeming at times to teeter in the breeze.

A backhoe took it down in 2011 just after preservationists were able to salvage some of its ornate interior, including a grand staircase.

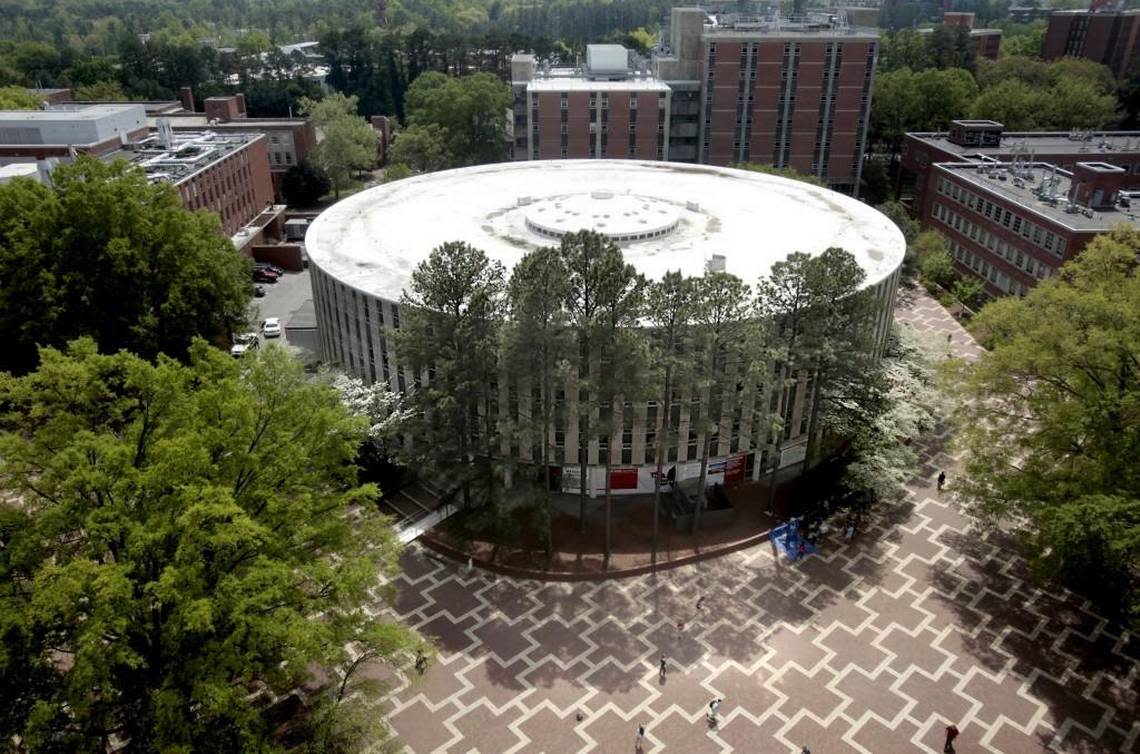

Harrelson Hall

By the end of its quirky history, the circular building on N.C. State University’s Brickyard had more detractors than fans — most of them students lost on its spiral ramps or trapped in the corners of its pie-wedge-shaped classrooms, where the chalkboards were impossible to see.

It grew out of a burst of 1960s creativity and stuck its tongue out at the bland boxes that surrounded it on campus.

But its daring design proved impractical. Windowless classrooms and noisy duct work frustrated young scholars, and the building’s chief purpose became recreational rollerblading.

In 2016, the campus had endured enough, and Harrelson came unceremoniously down.

Garland Jones Building

Much like Harrelson, its garish 1960s cousin, the Garland Jones Building lived long enough to see its design fall decidely out of fashion, with downtown pedestrians often calling it hideous.

But Raleigh’s characters kept a fondness for the downtown bank-turned-Wake-County-office, especially for its “curtain wall” of blue and white glass.

Its time and temperature clock were first to go, lasting only into the ‘90s. But despite anguished cries from Raleigh’s Modernist community, it got demolished along with its bomb shelter at Salisbury and Martin streets in 2009, making way for the new courthouse.

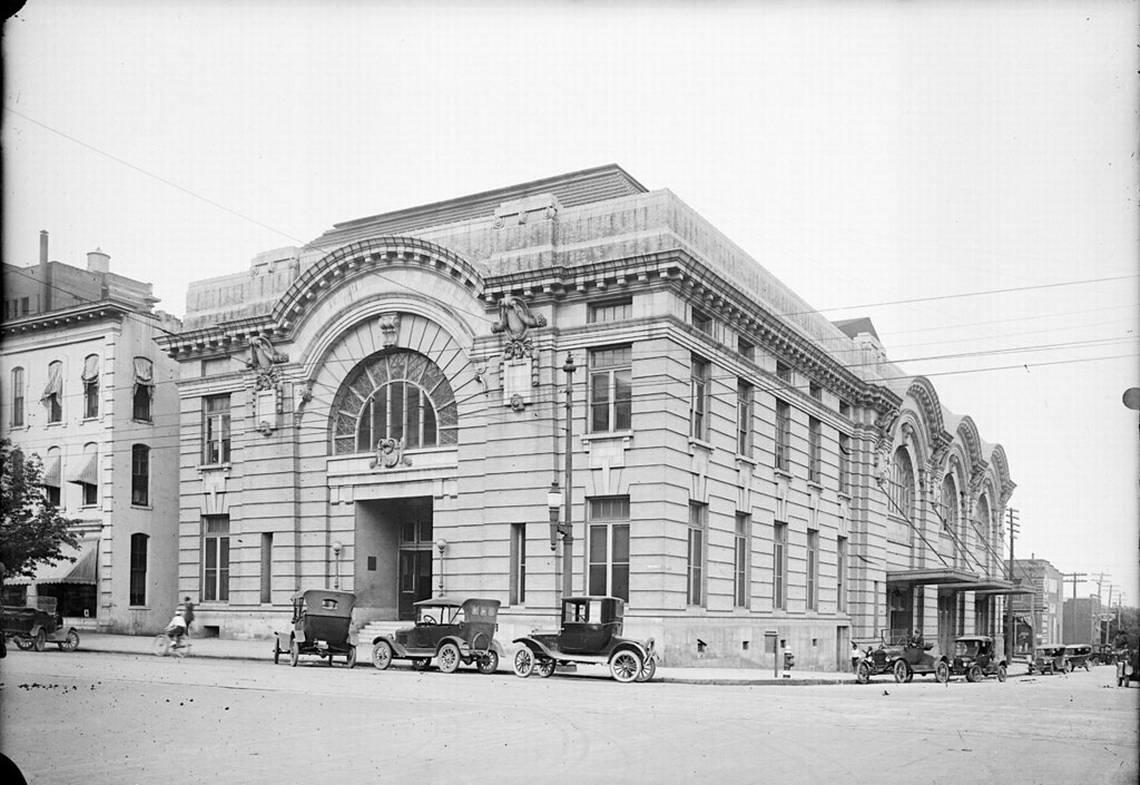

Old City Hall

The old City Hall building shared its space with its broad arches in the Beaux Arts-style on Fayetteville Street with an auditorium that seated 5,000 people.

President William Howard Taft spoke there, as did William Jennings Bryan fresh from his Scopes trial exploits.

“Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers and others had made the walls rock with merriment,” The N&O once raved.

But a devastating fire destroyed the auditorium in 1930, and the City Hall portion would come down in 1960, giving the grand downtown landmark a life of less than half a century.

When it got demolished, its wrecking company advertised the steel beams and marble tiles for sale in a series of classified ads.

Baptist Female Seminary

Standing five stories tall, loaded with cupolas, gables and turrets, the Baptist Female Seminary looked like a fairy tale palace painted red.

Built in 1899, it housed students at what was then an early version of what would become Meredith College. And it made a stately companion to the Governor’s Mansion a bit further down Blount Street — both of them built by Raleigh’s architectural star A.G. Bauer.

It held not only dorm rooms but also classrooms, laboratories and the dining hall, so the budding school for women found itself overflowing inside its castle, finally moving out over Christmas break in 1925 and relocating to Hillsborough Street.

It sputtered on as a hotel, then as apartments. But the state bought the Blount Street palace and in 1967 replaced it with one final indignity:

A parking lot.