It's Time to Unlearn Everything You Know About Sex

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

There are few things more American than apple pie—and one of them is a fear of sex. Watch any cultural weathervane spin and it inevitably points to some sort of panic regarding the carnal, the kinky, the fun. Takes about the death of the sex scene in popular culture have become cyclical. Even in ostensibly progressive corners of the country, the bizarre cry of “no kink at Pride” now recurs like allergy season. Is this some kind of pendulum effect? After we got the Fifty Shades of Grey books and the film trilogy? After Onlyfans made it into mainstream vocabularies?

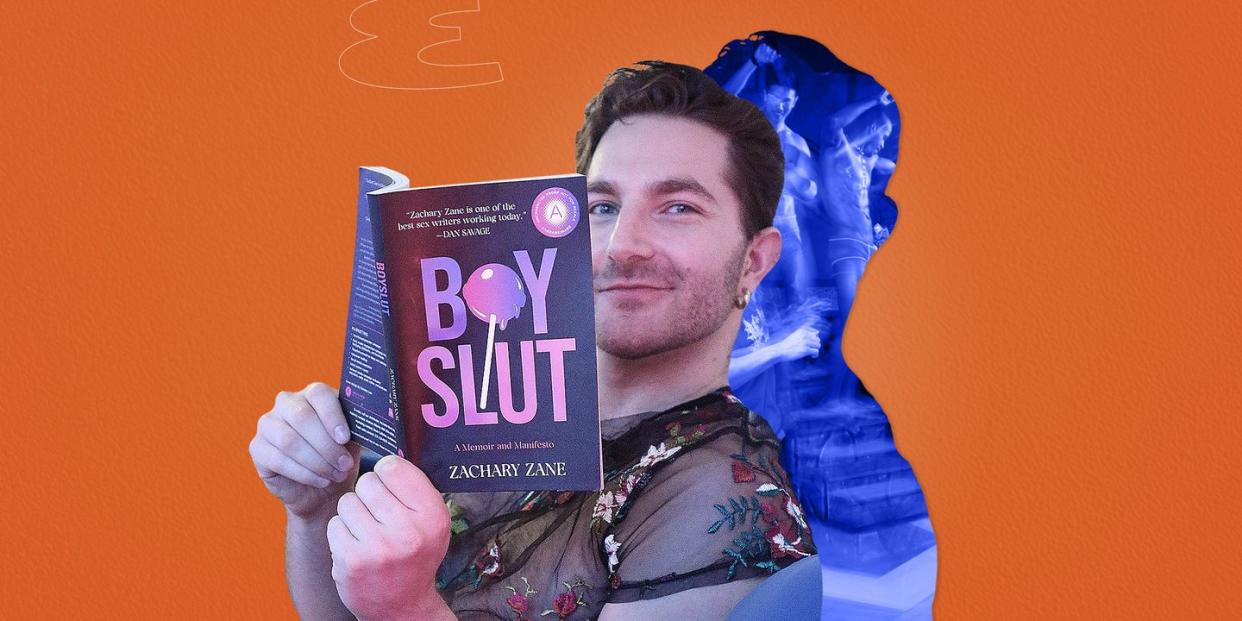

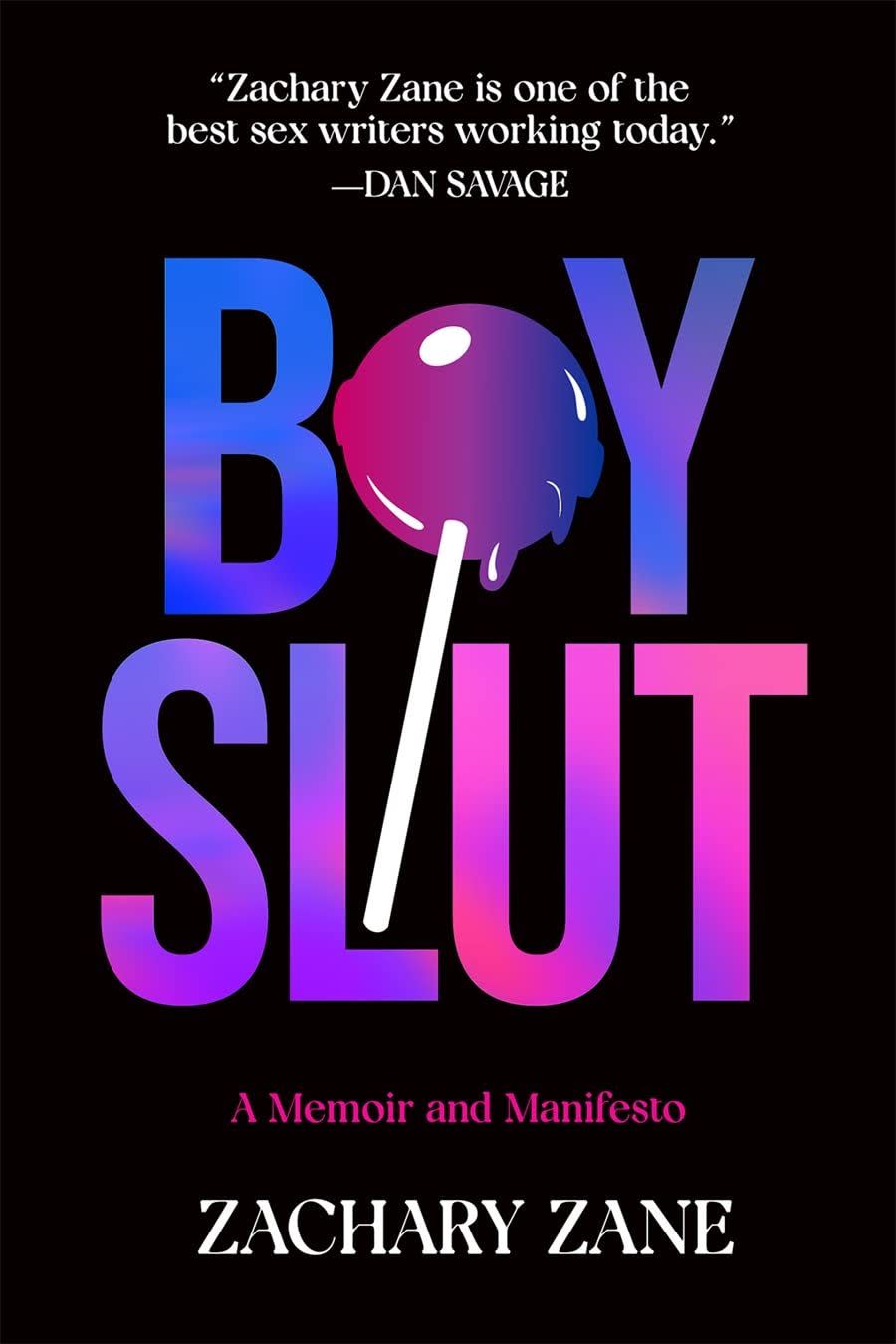

After sex has been on our screens and pages for so long, this country’s puritanical roots seem to have returned with a vengeance. The writer Zachary Zane believes that they never left. In his new book Boyslut: A Memoir and A Manifesto, Zane argues that, in much of American culture, “sex-negativity is pervasive, insidious, and touches us all—and not in a fun, kinky way.” As a sex and relationships advice columnist for Men’s Health and Cosmopolitan, Zane has seen how our society’s moralistic attitudes about our bodies and our sexual and gender expressions leave many of us limited and wanting for release. And so Zane wrote this book, “a confessional call-to-arms,” he tells Esquire, as both a memoir—a window into his own sexual life and experiences as a polyamorous bisexual man in New York City—and a manifesto—a window into what is possible through a healthy relationship with sex and with sexual partners: intimacy and play, connection and community.

Zane offers his personal stories not as a rulebook or a template for readers, but as data points and case studies, as examples of his own self-interrogations of internalized sexual shame. “Having sex has been the best way for me to learn about sex,” he writes in Boyslut. “[It] helped me unpack the structural systems that idealize an unhealthy masculinity, promote queerphobia, and perpetuate sex-negativity. I believe that if we can understand these systems, we can all unfuck ourselves.”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: Today, Boyslut is a memoir and a manifesto, as the cover says—but also it’s an online zine that you run. Which came first?

ZACHARY ZANE: I always knew that my first book was going to be called Boyslut. I made that decision before starting my newsletter of the same name, which began as a tool to build my audience so I can directly reach them once I published the book. Then the newsletter evolved into Boyslut the zine, with writers from across the globe writing nonfiction erotica. It’s really fun and raunchy. But I also want to make sure readers know that Boyslut the book is different from Boyslut the zine.

The zine really is just raunchy as fuck nonfiction, but the book is my memoir. It’s not just sex stories. It’s about what our society teaches us about topics like sex, bisexuality, polyamory, and masculinity, and unlearning that. In fact, when I submitted the first draft, my editor said that, for a book about sex, it actually wasn’t that sexy. I think my audience expects a certain amount of graphic sex in my writing, so I asked myself if I could add another chapter or two that gives the people what they want without compromising my intentions for the book.

How do you balance those two modes of writing?

It’s not too challenging, if I’m being honest. They’re just different hats that I put on. The zine, for me, is about fun. I publish it myself; I don’t have an editor or a team. So in that regard, the writers and I get to be as graphic, as vulgar, as explicit as humanly possible in how we tell these stories about sex. But when you’re working with a team on a book for a general audience, there are other expectations to manage.

$22.69

amazon.com

I want Boyslut the book to connect with a larger audience, to share this message of unlearning shame around sex. While writing it, I didn’t want the language to be too off-putting—and as it’s currently written, it might still be too off-putting for a lot of people. That’s just the style I write in. But I did want to be more inclusive and try to meet a general reader where they are. Though, with the zine, I’m less concerned because it’s my pet project.

And when I write brazenly about sex for the zine, it’s not just for shock value. Sex can look like this—kinky and raunchy and intense and playful—and there’s nothing wrong with that. I really think there’s power in Boyslut the zine being as graphic and explicit as it is. If it makes you uncomfortable, that’s a signal that there’s something you have to unpack about your relationship to sex.

There are lots of conversations happening online about sex scenes in television, films, and books, ostensibly about the value or merit they bring to art and storytelling. The way you describe Boyslut the zine as raunchy and fun reminds me that the explicitness is sometimes the point itself: sex can be raunchy and fun, and that’s a worthwhile human experience.

Exactly. It’s especially fraught when you read sex through the lens of bisexuality. For so long, in advocating for depictions of bisexuality in the media, I feel like a lot of bi activists were concerned about being palatable to both straight and gay people. They wanted to discourage stereotypes about bisexuals—that we’re slutty or love threesomes—so they would omit sex when talking about bisexuality. I really didn’t like this neutered form of activism. And I know for a fact that I’ve not been invited to certain bi spaces because my work and I have been deemed too explicit, or I might derail the conversation to be more about sex than sexuality.

For me, it’s important to show the sexual side of bisexuality, to bring that back into the conversation, and to make distinctions between bi stereotypes that are inherently bad and ones that are not. Like, there’s nothing wrong with being slutty. There’s nothing wrong with wanting threesomes. But then there are some negative stereotypes like, “Bisexual people are cheaters. They’re greedy. They’re liars.” Those are actually harmful. Of course, you should not stereotype and assume that one bi person’s desires and experiences apply to all bi people. Some bi people are slutty or love threesomes; some bi people don’t. Personally, I’ve leaned into being this bisexual stereotype and I’m very proud of that. In the past few years, I’ve noticed more people leaning into stereotypes in a way that, I think, can actually be quite affirming.

The idea of leaning into a stereotype is really interesting to me. It’s something I also talk about in my book The Groom Will Keep His Name: using sexuality as a tool to get what I want as someone who is Asian, gay, and more feminine—and how that blew up in my face. While I was writing, there was sometimes a tension between writing a truthful and honest version of myself on the page against the lingering knowledge that people will try to read my individual experience as representative of a larger group. Did you have that internal conversation as well?

Oh definitely. But you can’t win it—you know what I mean? It’s a nuance that I worked hard to incorporate into the book, being like: “Hey, this is my experience. This might resonate with some bi people, or other people regardless of gender or sexual orientation. But this is not everyone else’s experience. It’s only mine.”

A lot of what I tried to write about in the book is the idea that you should be free to do whatever you want, to do it with the consent of your partner or partners, and to do it healthily. There’s no one way to be bisexual. There’s no one way to engage in kink or sex, and no perfect amount of sex you should have with your partner. What I’m advocating for is being able to pick what is right for you and to see that there are options you might not have even realized in terms of how to engage with sex, and how to have certain relationships. I’m not putting one or another on a pedestal. I’m not saying that my experience is the only experience. But hopefully, someone reading about how I live my life can find some resonance with it, something like a jumping off point to explore their sexuality, to start unlearning the ways we’re taught by society to feel shameful about sex.

That seems to be the ultimate double-edged sword about that fraught idea of representation. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Especially when you’re in a marginalized group. Though we’re getting more and more bisexual characters in pop culture, there’s still not a lot of them. And when there’s little visibility, there’s this pressure that every depiction needs to be perfect, that a bisexual cannot look bad in any shape, way, or form. But that deprives us of nuance, and of the fact that, of course, no group is perfect. It doesn’t do anyone a service if we sweep the less perfect aspects of an individual character or a group or a community underneath the rug. We need to address some of the less than ideal aspects of our lives. We have to be honest with each other and with ourselves.

It’s a lot like what happens in fiction, when attempts at representation are met with backlash because, say, a queer character behaves badly in a TV show. It’s often read as “bad representation,” when in reality, we know there are some evil queers out there.

I remember this happening when the reality TV show Fire Island came out. Not the Hulu movie—that was great. But with the reality show, everyone was like, “This is not how gay men are! We’re not this petty or toxic!” It’s like, have you not met a fucking gay man? We all know guys like that. It’s the same thing when a gay character is stereotypically like, “Yes, bitch! Work, sis!” People will react and say, “We’re not all this queeny.” Sure, but many gay guys are. So the framing shouldn’t be, “We can’t have representation like this.” I think we just need more depictions, broader depictions, more diverse depictions of queer life, so that one doesn’t have to represent all.

Part of this cultural conversation about representation is often focused on fiction, on characters that are depicted on screen or in books, but they’re fundamentally not real.

And depiction doesn’t mean endorsement. You're using a character maybe as a foil, but it doesn’t mean that the character is meant to stand in for a creator. This is what a creator wants the world of work to look like, and that’s just how some people are in that world.

Exactly. But Boyslut is different: it’s nonfiction. You pull from things that have actually happened and present them as real. In your view, how much of those standards of representation carry over to the realm of nonfiction? Are they even applicable?

A lot of those conversations do carry over to nonfiction in ways that they shouldn’t. The framework is fundamentally different. You’re talking about someone’s actual lived experience. You can’t take that away from them. But I still do get that kind of critique, and it’s challenging. It’s like, “I didn’t depict being bisexual or poly in the way that you want and so you say my own poly bisexuality is wrong.” It feels much more like a personal attack. People can read my work and disagree with what I say, for sure. But it’s another thing when they try to invalidate the way that I live my life.

What do you hope this book does for an average reader? Someone who’s not super sexual; someone who could be queer, or could be straight; someone in the middle of a bookstore seeing the word Boyslut? What do you want them to get out of this reading experience?

There are two different things. Even if you’re not having a lot of sex, you may be questioning your sexuality or overcoming shame about sex. If you’re someone who grew up and lives in this world of ours, you have sexual shame. It’s just that insidious and pervasive. We get it from media, culture, teachers, and friends. So I hope this book helps a reader unpack that shame.

The other element is that I hope the book broadens people’s horizons. I hope the stories in the book show the varied options available to us as sexual beings. If you’re not comfortable identifying as bisexual, it’s like, okay, well, there are other ways to explore this. Or if you don’t want to be completely polyamorous or in an open relationship, you might be monogam-ish. That’s something you can explore with a partner. These days, even now, there’s a limiting way to how we talk about sex, and how we’re supposed to date and love. I hope Boyslut depicts the various options worth exploring or the ways we can experiment in our personal lives. That’s what I want the book to offer: discovery.

You Might Also Like