Three years in, Fort Worth ISD partnership with Texas Wesleyan shows promise

Five years ago, there was always a certain amount of chaos in the hallways of John T. White Elementary School, Julissa Gomez said. The school — which rated an F in the state’s accountability system — was short on supplies and equipment, and teachers didn’t have the support they needed, she said.

Today, the hallways at John T. White are mostly quiet, teachers have more planning time, and struggling children get more individualized instruction, Gomez said. The school received a B in the state’s latest accountability ratings.

Gomez was a second-grade teacher at John T. White five years ago. She’s now the school’s assistant principal. As she has changed roles, she has also been part of a change in culture and strategy at the school.

Students and teachers still have good days and bad days, she said. But in general, the school has a more enriching learning environment than it did before, she said.

“It sounds cliche, but people seem happy to be here, and the students enjoy coming to school,” Gomez said.

John T. White is one of six schools in the Fort Worth Independent School District’s Leadership Academy Network, which began in 2017 as a turnaround project for struggling schools. Two years later, the district partnered with Texas Wesleyan University to operate those schools. As a part of that transformation, those schools got an extended school day, extra tutoring for students and more support and coaching for teachers.

Since then, those schools have seen rapid progress, and the partnership now serves as a model for how the district can help other low-performing campuses.

Struggling campuses transformed into ‘leadership academies’

In 2017, the district transformed five chronically struggling schools into leadership academies as a part of a $5.5 million effort to help the schools better educate children. All five schools — Mitchell Boulevard, Como, John T. White, and Maude I. Logan elementary schools and Forest Oak Middle School — received an “improvement required” designation in that year’s state accountability ratings, indicating they failed to meet state standards.

Following the change, students spent longer hours at school, eating breakfast, lunch and dinner there. Teachers were required to do a better job of engaging with students and their families, including through home visits. The district offered annual bonuses of $10,000 for teachers and $15,000 for campus leaders who worked at the leadership academies, and used test scores to identify teachers within the district whose students outperformed expectations and recruit them to serve at those schools.

The extended school day also allowed school leaders to schedule tutoring for students who were struggling. Teachers also received extra instructional coaching to help them hone their craft.

Then, two years later, the district’s school board voted to approve a partnership with Texas Wesleyan University to operate the schools under guidelines laid out in Senate Bill 1882, which state lawmakers passed in 2017. The bill offers financial incentives for districts to partner with charter operators, nonprofits or colleges and universities to run schools. Those schools remain zoned neighborhood schools in the public school district, but the partner organization is left in charge of all decisions regarding staffing, curriculum and finances. The district continues to provide certain services the partner organization can’t offer, such as transportation and special education programs.

Although district officials said at the time that the schools were showing signs of progress, the turnaround didn’t happen overnight: All five schools received D or F ratings in the 2018-19 state accountability ratings, the last set of ratings the state issued before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In August 2022, all five of those campuses received an A or B rating. John T. White jumped from an F rating in 2018-19 to a B rating this school year. The percentage of third graders scoring at grade level this year at the network’s four elementary schools continued to lag behind the rest of the district, which itself lagged behind the rest of the state. But the Texas Education Agency gave all five campuses high marks for school progress and academic growth, which boosted their overall ratings.

At the beginning of the 2020-21 school year, the district added a sixth campus, Forest Oak Middle School 6, formerly known as Glencrest 6, to the partnership. That campus, now known as the Leadership Academy at Forest Oak Middle School Sixth Grade, continues to struggle. The TEA gave the school a score of 58 on this year’s A-F accountability ratings. In a typical year, that score would translate to an F rating. But the agency didn’t award Ds and Fs this year due to a change in state law.

Bilingual support grows in Fort Worth leadership academies

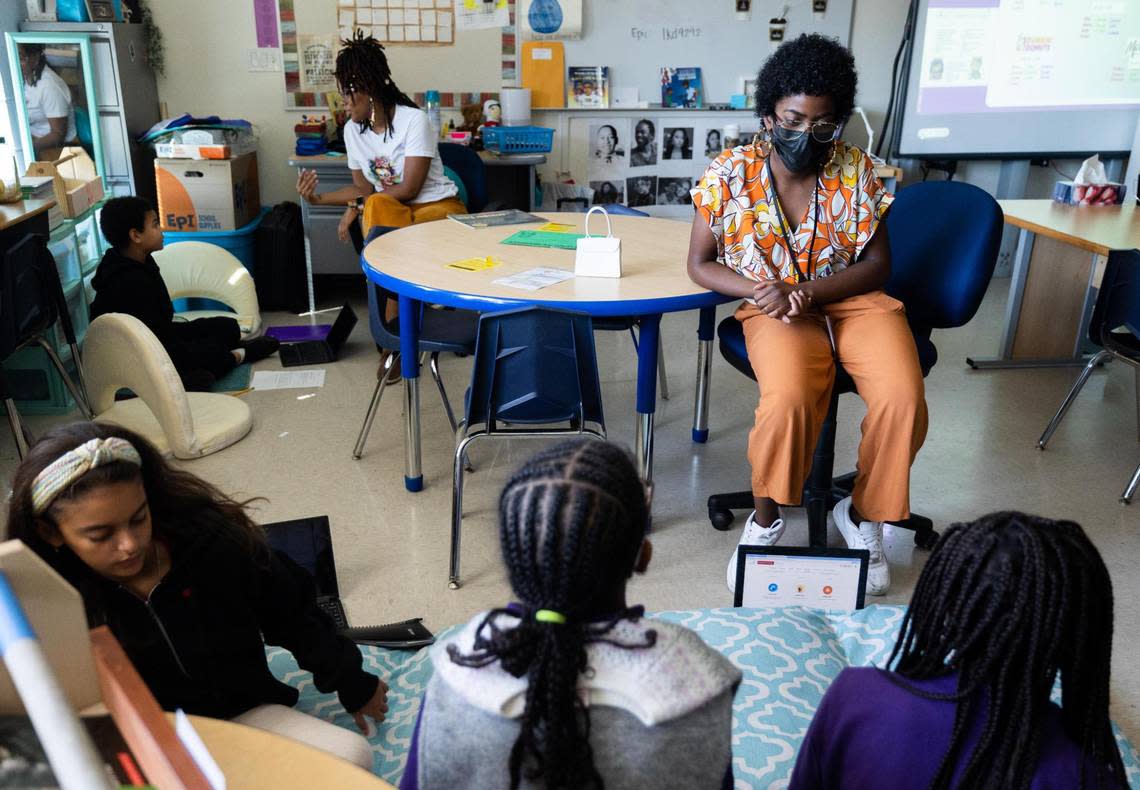

On a Thursday morning in early October, students sat in groups on couches or on the floor of Latressha Leonard’s fourth-grade classroom. They looked over lists of discussion questions about books they just read. Students at the school participate in book clubs, where they pick books they want to read and then meet with other students who picked the same book to talk about the author’s intent and how what they read applies to the real world.

A few doors down, in Zaida Johnson’s fourth- and fifth-grade bridge class, students did the same. But in this classroom, the books and the conversations were in Spanish. Johnson is a bilingual teacher, so students switch between English and Spanish in her class in alternating weeks. One group of students read a book about frogs, while their classmates on the other side of the room talked through questions about a novel for young readers.

Increased support for bilingual learners was one of the biggest changes after the school moved into the Leadership Academy Network, said Gomez, the assistant principal. Teachers got professional development that was better tailored to the school’s specific needs, she said. As a bilingual teacher, she got one-on-one instructional coaching — something she’d never had before.

The school also got more resources for bilingual students, she said. Before the change, Gomez would spend her own money buying bilingual books or stay up late to translate books and short passages so her students would have the same learning opportunities as single-language learners. Now, the school is more intentional about planning for the needs of bilingual students, she said. That change didn’t happen in a single year. And it doesn’t just include Spanish speakers, she said. There’s a growing need at the school for bilingual education for students who speak Burmese, she said. Given the need, she’d be happy if every student at the school had access to bilingual education.

“We live in Texas. It’s a bilingual state,” Gomez said. “So there’s a huge need, I would say a 1000% need for bilingual education here.”

One of the other noteworthy changes was a greater emphasis on social and emotional learning, Gomez said. Teachers received training to support students emotionally and make sure to attend to the whole child, not just focus on test scores. That means forming deeper relationships with students to make sure they feel safe and supported at school, she said. If students aren’t able to regulate themselves emotionally, they aren’t in a position to learn, she said.

That increased emphasis on building relationships with students and their families made life a bit easier at the beginning of the pandemic, when the district shut down schools and shifted to online learning, Gomez said. Because those relationships were already built, she had names and phone numbers of her students’ parents and an idea of their work schedules, and they were already in the habit of having regular phone conversations, she said. That didn’t make the transition easy, she said, but it was one challenge she didn’t have to deal with.

Better results help improve John T. White’s reputation, father says

Stefon Cheatham’s 8-year-old son, A’mir, is in third grade at John T. White. When Cheatham moved from Grand Prairie to Fort Worth before A’mir started school, what he heard about John T. White was mostly bad: high staff turnover, low test scores and families feeling reluctant to send their kids to school there.

But since the change, Cheatham has been happy with what he’s seen. Cheatham, who is the senior pastor of Little Friendship Baptist Church in Dallas, volunteers regularly at the school, which gives him a chance to see teachers working with students. The teachers are dedicated to doing what’s best for their students, he said. He often sees teachers there check on their former students who have moved on to higher grades, he said.

A’mir likes the extended school day because it gives him more time with his friends, Cheatham said. It also gives teachers at the school more opportunities to work one-on-one with students and give them the attention they need, he said.

Texas Wesleyan partnership offers flexibility

Priscila Dilley, senior officer of the Leadership Academy Network, said one of the main benefits of the network is flexibility. In a district the size of Fort Worth ISD, it can be hard to provide tailored support for a school that’s struggling, she said.

Dilley, who served as the district’s executive director of innovation and transformation before moving to Texas Wesleyan to manage the partnership, said the network’s six schools are able to operate like a smaller district within Fort Worth ISD. If a school has something it wants to try, it’s easier for the network to put it into place quickly, without having to navigate the processes and procedures of a larger organization, she said.

Dilley said the extra hour of school each day is a major part of the network’s success. Besides giving students more time to focus on reading and math, it also allows schools to schedule more planning time for their teachers, she said. That extra planning time gives teachers the opportunity to prepare higher-quality lessons that are more closely tailored to what their students need, she said.

The partnership has also given the district a way to try new ideas on a smaller scale before implementing them district-wide, Dilley said. For example, when the district considered adopting a math curriculum from Carnegie Learning, the schools in the network tried it first and found that it was helpful. Later, Fort Worth ISD rolled the curriculum out across the district. Being able to try those ideas in a few schools gives the district a chance to get any kinks worked out in a setting where it won’t cause as many problems, she said.

“Now, I tell them, ‘Let me make all the mistakes,’” she said.

Fort Worth ISD brings leadership academy principles to other schools

David Saenz, Fort Worth ISD’s chief of innovation, said the district is now looking to apply the same principles that led to progress at the Leadership Academy Network schools to five other struggling middle schools. The network was established using principles borrowed from the Accelerating Campus Excellence, or ACE, model pioneered by Dallas ISD. Those principles included an extended school day, after-school tutoring, extra support for teachers and a focus on enrichment activities, he said.

Like the schools in the network, those struggling middle schools can expect curriculum changes and an extra focus on after-school extracurricular programs, he said. But mainly, the change will mean more support and instructional coaching for teachers. That was one of the key lessons the district learned from the network, he said.

“You can throw everything else at it,” he said. “You can do the after-school work, you can do all the enrichment pieces, but you’ve got to start with a strong core of instruction.”

Saenz acknowledged that the newest Leadership Academy Network campus, Forest Oak 6, continues to struggle. But district officials are confident that campus will turn around, he said. The district’s eventual goal is to merge the sixth-grade center with Forest Oak Middle School, he said, bringing grades 6-8 under one roof. A bond package voters approved includes money for an expansion at Forest Oak Middle, which will allow the district to move sixth-graders there, he said.

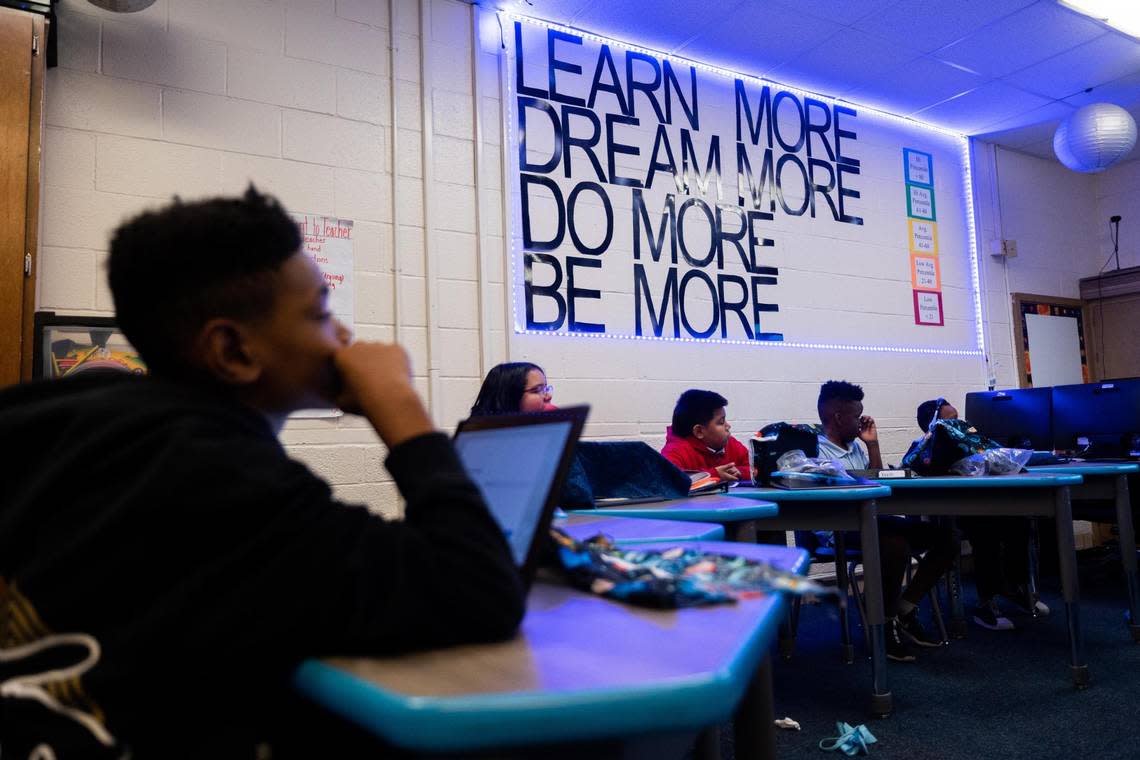

Longer school day gives teachers more opportunities

Tanysha Walls, a fifth-grade science teacher, is in her eighth year teaching at John T. White. She’s been there long enough to see the transition to the Leadership Academy Network. The change brought more support for the school, and the longer school day meant that teachers could do things with students that they couldn’t have done before, she said. It also left time for struggling students to get more individualized help, she said. At first, though, asking students to spend more hours at school per day was a tough sell, she said.

“It was very different, for sure,” she said. “They wanted to know why, why, why?”

One of the other major changes was easy access to information about how students were doing. At the end of each lesson, teachers in the network give students a brief quiz on the material they covered. The students answer three or four questions on their tablets, and teachers can see instantly how they did.

The questions are less about assigning grades than they are about seeing how well the class understood the lesson. If one or two students miss the questions, the teacher can pull them aside and walk them through the material again. If half the class gets the questions wrong, teachers know they need to go back and teach the lesson again. That information is crucial, Walls said, because it means she doesn’t have to guess which students have mastered a concept and which need a little extra help. Now, everything she does is data-driven, she said.

But Walls said even the best data can’t replace a strong relationship with her students. That relationship starts with her trying to meet students where they are, she said, and also with her showing students that she’s a human being, as well. Many students aren’t able to see their teachers as real people, she said; they only see them as authority figures. So she tries to let her personality come through in class.

“They always hear about my five dogs that I have, and they love them,” she said.

Quizzes give insight into how students are doing

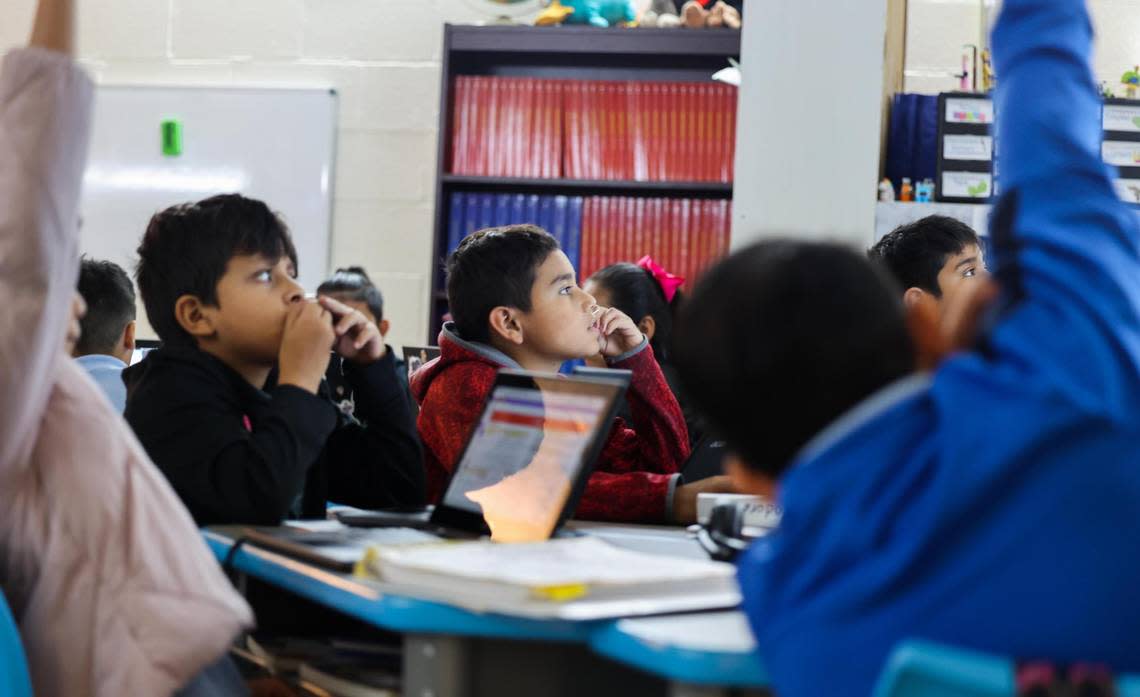

On the same October morning, about seven miles southwest of John T. White, Agustin Tiliano walked students at Mitchell Boulevard Elementary School through a lesson on text structures. Switching seamlessly between English and Spanish, Tiliano talked about the similarities and differences between realistic fiction and nonfiction, and how to tell one from the other. At the end of the lesson, he had students answer four questions on their tablets.

Within a couple of minutes, he had a clear picture of which students understood the lesson and which needed more help. That allowed him to pull those who needed help aside and walk them through the material again. When he re-teaches a lesson, it’s important that Tiliano focuses on bringing students up to grade level, he said, rather than aiming too low. He has high expectations, which means he has to give students instruction that helps them meet those expectations, he said.

Tiliano, who is in his third year of teaching at Mitchell Boulevard, said data from the quizzes can also help inform conversations with parents. When parents want to know how to support their children’s learning at home, he can use that information to tell them what their kids are struggling with.

The data also helps students see their own progress, Tiliano said. Students have access to their own scores in Google Classroom, so they can look back over a six-week grading period, a semester or an entire year and see how far they’ve come. That can be motivating for students who struggled at the beginning of the year, he said.

Leadership Academy model means more support for schools

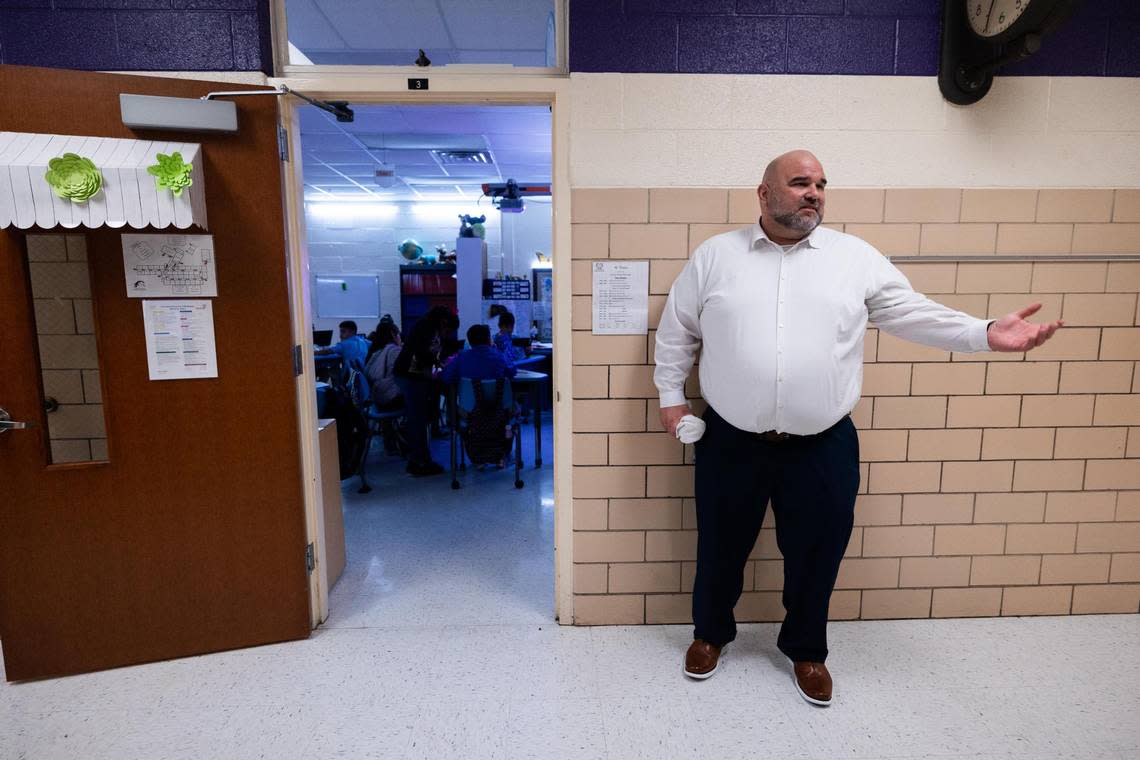

Danny Fracassi has been with the network since its inception, first as an assistant principal, and now as the principal of Mitchell Boulevard Elementary, which jumped from a C rating in 2018-19 to an A rating this year.

Fracassi said the most noticeable change that took place under the partnership was that, because of the network’s small size, its leaders are more accessible to principals and teachers than Fort Worth ISD’s central office officials were ever able to be. That means it’s easier for each individual school to get support when it needs it, he said.

For example, when teachers had questions about the curriculum before the change, it was unlikely that the teachers or their principal would be able to talk to the person who wrote the curriculum, Fracassi said. Now, because the schools in the network developed their own curriculum, there’s a good chance that the person who wrote the curriculum is already in Fracassi’s building. If not, it only takes a quick phone call to one of the other five schools in the network to track down the answer, he said.

That quicker response time means that school administrators can get teachers what they need more quickly, which means fewer interruptions in the classroom, he said. That means teachers are better able to spend their time and energy working with students, he said, rather than trying to track down things they need or get questions answered. Ultimately, that means students get more attention from their teachers, he said.

“The quicker we as principals can take care of the staff, they can then, in turn, take care of our kids,” Fracassi said. “And then our kids can, in turn, grow, which is the ultimate outcome.”