Who was Tenskwatawa? How a Shawnee tribal leader who resisted U.S. treaties ended up in KCK

Well before Kansas or Missouri were declared official territories, much less official states, dozens of Native American tribes called the land that is now referred to as the Kansas City metro home.

One reader asked KCQ — the collaboration between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library that seeks to answer Kansas Citians’ questions about KC history and quirks — if we could uncover more information about the Native American tribes that used to live and still live in Kansas. The state is filled with Native American history and culture, and there is no way we could do it all justice in one story. So instead, we decided to focus on one specific story of resistance and perseverance.

In the 1820s and 1830s Native American nations like the Shawnee Tribe were relocated to Kansas from the Old Northwest territory, now present-day states Ohio, Illinois and Indiana.

The Shawnee received nearly 1.6 million acres of land in what was then known as the Great American Desert, that same area would become the territory of Kansas in 1854.

Before the territory was established, it was first home to the Osage, Kanza, Pawnee, Comanche, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa and Wichita. The Shawnee would become one of at least 30 tribes to emigrate to the area in the 1830s.

But years before the United States’ conquest for land forced tribes like the Shawnee to keep relocating, there was a brewing resistance movement led by two Shawnee brothers, whose mission was to unite tribal nations and reject American treaties.

Around 1805, the two brothers, Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh would start a movement that encouraged Native Americans to push back against white settlers and denounce assimilation.

Tenskwatawa, in particular, had a series of spiritual awakenings in the early 1800s. These callings were the foundation for this movement, and he would eventually be known as the Shawnee Prophet.

Callings from God

In his callings, historian Adam Jortner said Tenskwatawa received instructions from the “Master of Life” on how Native Americans should live. According to those callings, Native Americans were to return to their religions, abstain from drinking alcohol, stop fighting neighboring tribes for land and give up white customs and traditions.

“He really is a religious leader and I think he gets pulled into politics because one of his biggest teachings is there are no more tribal differences,” said Jortner, author of The Gods of Prophetstown. “He started teaching that all Native Americans needed to work together. They needed to get they were going to become one people, because that’s what the Master of Life wanted.”

Tenskwatawa’s visions for his people led to a powerful resistance and a self-sustaining, off-grid, settlement, which would eventually be known as “Prophetstown.”

The settlement began in Greenville, Ohio in 1805. It was said to be a mosaic of tribes from all over the country, living in harmony, while maintaining their own district national heritage. In addition to Shawnee, Tenskwatawa had followers from nations including Seneca, Ottawa, Ojibwe, Ho Chunk and Potowatomi.

“He was calling upon tribal nations to come together and band together in the spirit of resistance against the United States westward expansion,” said Shawnee Chief Ben Barnes.

Both Tenskwatawa, Tecumseh and other deputized followers would travel the country to share Tenskwatawa’s vision and invite other Native Americans to join their village.

“So Tecumseh was almost like a general. He was a war chief. So he led men in battle whereas Tenskwatawa was a spiritual leader. He was telling us people to go back to the religions of your grandparents, no matter who you are, or where you’re from,” Barnes said.

By 1806, Tenskwatawa saw an uptick in followers after he successfully predicted that there would be an eclipse, according to Ohio’s historical society. People saw this as a testament to his enlightenment and began to flock to the village. The village would last from 1805 until 1811, and at its peak there were around 800 to 1,100 villagers, according to historian Stephen Warren.

“So his message really resonated with people across linguistic lines,” said Warren, author of The Shawnees and Their Neighbors, 1795-1870. Warren added that Tenskwatawa’s teachings were even translated into the languages of neighboring native nations.

The Battle of Tippecanoe

Pressures from United States officials, including the Territorial Governor of Indiana William Harrison, would force the settlement to move three times in that six-year time span, despite treaty agreements. By 1811, those pressures pushed Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh into battle in order to defend their village.

“Tenskwatawa is ultimately defying the US in the 1810s and saying, ‘No, this system of treaties is garbage. It’s not how we see ourselves. It’s not how God wants us to do it. And if you think you’re going to do it, you can come here and make me,’” Jortner said.

Gov. Harrison led American soldiers to Prophetstown in 1811. On November 7, 1811, before dawn, Tenskwatawa warriors made the first move, attacking the American soldiers who were encroaching on their land. This was the beginning of the Battle of Tippecanoe.

Jortner describes the battle as a draw, since both sides suffered some losses. However, after the battle, American soldiers burned down Prophetstown, and the people of the village dispersed.

Tenskwatawa and his brother Tecumseh went on to fight in the War of 1812. Tecumseh lost his life in battle in 1813 and Tenskwatawa lived in exile in Canada for years.

The Shawnee Prophet comes to Kansas

By 1826, Tenskwatawa made an arrangement with the Territorial Governor of Michigan Lewis Cass to recruit and relocate the Shawnee from Ohio and Indiana to present-day Kansas, according to Warren.

The Shawnee Prophet recruited approximately 250 people to Kansas, Warren said. The Shawnee weren’t alone in that removal process either. In 1825 and 1830, Congress would pass laws that essentially forced Native Americans to move westward to make room for American expansion.

By 1830, the Cherokee, Wyandot, Iowa, Chippewa, Delaware, Munsee, Ottawa, Peoria, Piankashaw, Quapaw and more were all given land in the area that would make up Kansas. Although the deal was that emigrant tribes would not have to move again after relocating to Kansas, many were still forced to move again after the Civil War once white settlers decided to make Kansas their new home, according to the Kansas Historical Society.

Tenskwatawa and his immediate family would settle in the Argentine area of present-day Kansas City, Kansas. The Prophet’s home near the White Feather Spring in the Argentine neighborhood would mark the heart of the last Prophetstown of the Shawnee, according to the marker at the site. In 1836, Tenskwatawa died and was buried there.

In his last days, Warren said that Tenskwatawa was treated like an outcast. Most of the Shawnee who relocated to the area lived further in Kansas, closer to today’s Johnson County. Tenskwatawa lost much of his following, and his methods were seen as controversial to some. Yet, the Prophet’s legacy is still a source of pride for many Shawnee.

“In the case of Tenskwatawa, the full might of the U.S. government was thrown against the Shawnee, and all of these various allied tribes, and they managed to withstand it, and to actually defy it,” said Jortner, adding that it’s important to understand how leaders like Tenskwatawa and many other Native American leaders opposed and resisted U.S. expansion.

The spirit of perseverance lives on

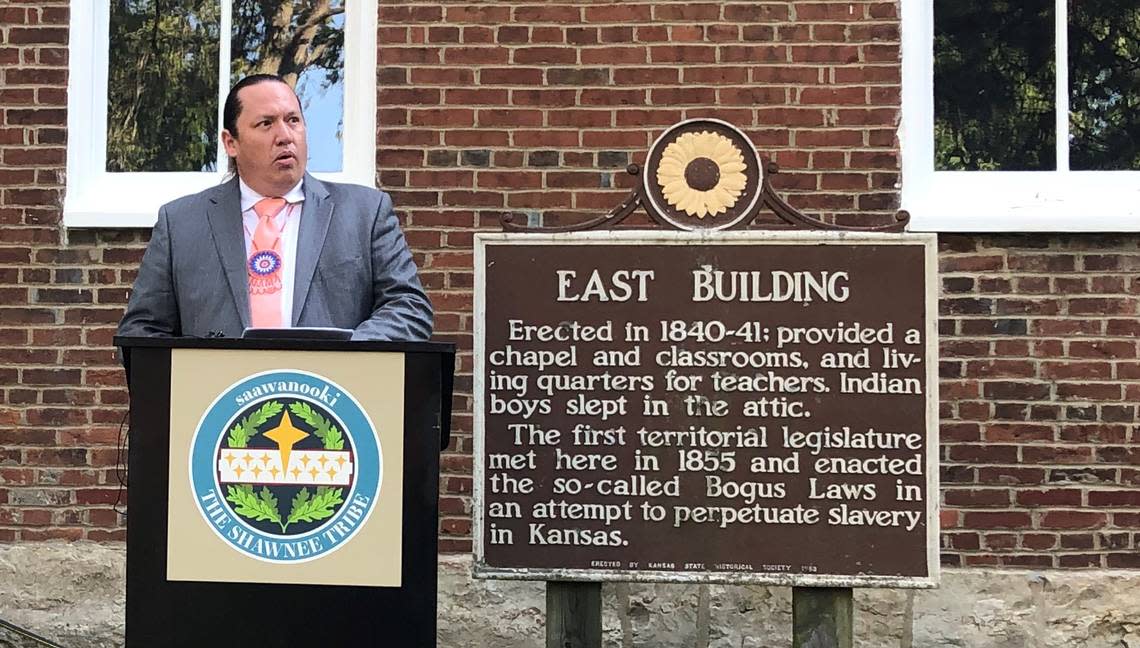

Leaders like Chief Ben Barnes are still fighting to this day to preserve the history and make sure the legacy of the Shawnee people is preserved and properly studied.

Following the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the U.S. enacted laws establishing and supporting boarding schools, intended on assimilating Native American children to white culture and customs. Thousands of American Indian children were forcibly placed in these boarding schools.

The Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School in present-day Fairway, Kansas is a part of that legacy. The school was established in 1839 by Johnson County namesake, Minister Thomas Johnson. The Shawnee were coerced into giving up 2,000 acres of their own land, plus funding for the school. Kids who were forced to attend faced terrible conditions.

“The kids were covered in lice. They weren’t being properly clothed, they were malnourished, and they were sleeping in the attics,” said Barnes.

Barnes is currently calling on local and federal officials to help the Shawnee preserve the school building and survey the grounds to better understand what took place there.

“We know that kids attended there, we know that kids died there. That’s a historical fact. What we don’t know is how many. We won’t really know that until a thorough historical survey is done,” Barnes said.

Barnes said the story of Tenskwatawa fits squarely into this effort to preserve the Shawnee Indian Manual Labor Boarding School because they both are a testament to the perseverance of the Shawnee people.

“Every time I see those buildings in Fairway, Kansas, I’m like, ‘We’re still here, we still survived. They didn’t take my language, they didn’t take my culture, they didn’t take our traditions, and they didn’t take our religion,” Barnes said.

“We are still here.”