Teachers enraged that Florida’s new Black history standards say slaves could ‘benefit’

The approval of Florida’s new Black history curriculum didn’t surprise Crystal Etienne.

A seventh-grade civics teacher in Miami-Dade County, she has seen it coming since 2022. She attended several civics training sessions over the last year — including the one where the instructor claimed presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson opposed slavery, even though both were slave owners — so the changes were somewhat expected. Still, the state’s newly adopted standards for teaching Black history left Etiennne mortified.

The Florida Board of Education certified the new standards Wednesday, causing an uproar among many. Some of the more concerning changes included teachings about how enslaved people benefited from their bondage, an attempt to contextualize American slavery within the global history of slavery and the false equivalence of anti-Black violence with acts of Black resistance.

Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-Orlando, who attended the Wednesday meeting, pointed to part of the middle-school standards that would require instruction to include “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

“I am very concerned by these standards, especially … the notion that enslaved people benefited from being enslaved. It’s inaccurate and a scary standard for us to establish in our educational curriculum,” Eskamani said.

Etienne, the West Homestead K-8 Center teacher, was equally disturbed.

“It’s disgusting to use children as pawns in their adult scheme,” she said, calling the changes an “indoctrination” into “white, Christian nationalism.” “They feel like if you’re teaching the bad, it somehow takes away from the good and it doesn’t. If I’m not allowed to teach the evolution of the country and the changes that have been made, what am I doing?”

“This is fascism at its best,” added Karla Hernandez-Mats, president of the United Teachers of Dade, which represents teachers in Miami-Dade public schools. “This is exactly what fascist governments do when they censor teachers, when they go after education, when they try and suppress content from being taught.”

Since the Florida Legislature passed a slew of education laws over the past two years — from giving parents power to challenge books to restricting how gender identity and sexual orientation is taught from Pre-K to eighth grade — teachers have been worried, Hernandez-Mats said.

But these changes related to Black history are “not a way that students should be educated,” she said.

“This is narrowing minds,” Hernandez-Mats said. “We want children to be well-rounded, well-educated, to have access to high-quality education... when you restrict teachers from teaching with honesty and teaching with truth, obviously that’s going to impact conversations that we’re able to engage in with our students.”

Follows changes to AP African American course

The controversy over how Black history will be taught in Florida’s public schools follows a decision by the College Board earlier this year to leave out references in its new AP African American Studies course to the Black Lives Matter movement and slavery reparations, among other topics. The Board’s decision came after Gov. Ron DeSantis criticized the pilot course.

READ MORE: Black leaders blast College Board’s changes to AP African American Studies course

Florida already underperforms at teaching Black history. Although the instruction has been required since 1994, only 11 of the state’s 67 school districts sufficiently teach Black history, according to Bernadette Kelley-Brown, principal investigator and former chair of the African American History Task Force, which monitors how districts heed the law.

“This new statute now basically says if African American history is being taught, it is going to be taught in such an inappropriate, historically inaccurate, watered down way that it makes it untenable,” said former State Sen. Dwight Bullard, a Democrat, who attended the Board of Education meeting in Orlando on Wednesday.

The meeting seemed designed to deter the average person from going, Bullard said. It was held on a weekday in the back of resort with $28 parking (more than $30 for valet). After the guidelines were explained, a public comment portion ensued during which the vast majority opposed the changes. Then the board voted to approve the curriculum.

“’How is it that a group that has no racial diversity basically bringing forward changes to African American studies and history that African American folks who have spoke are actively opposed to,’” Bullard said.

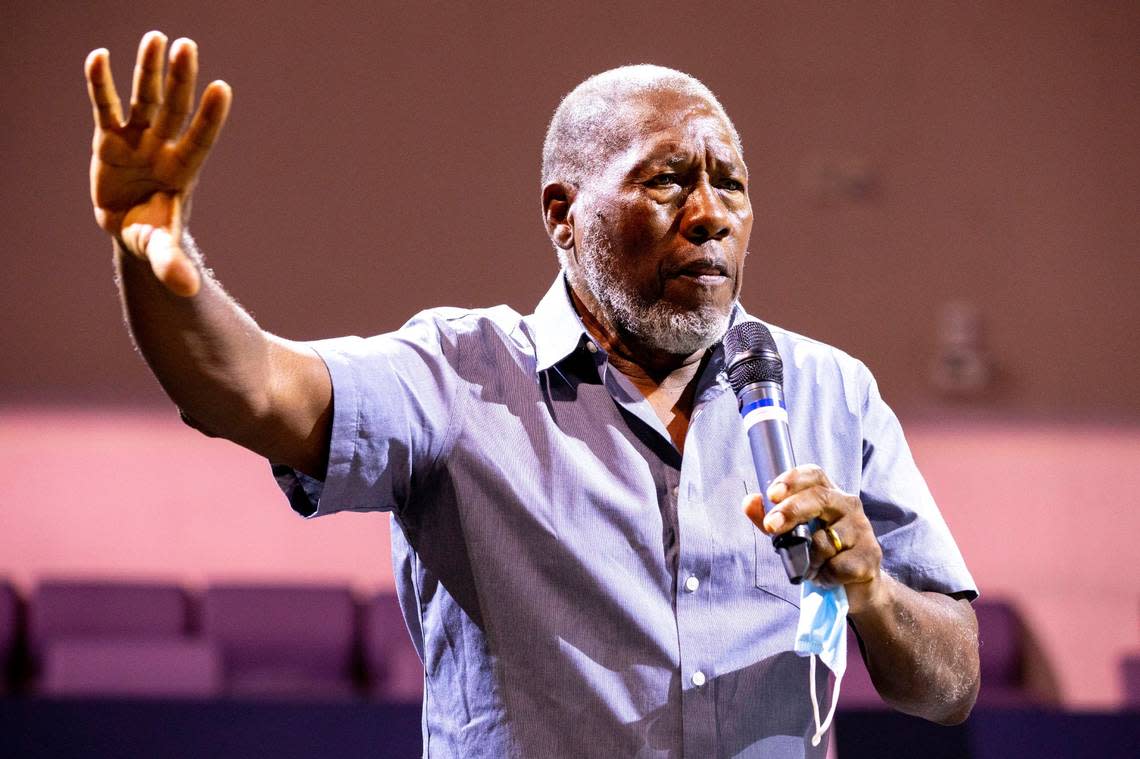

A former high school history teacher, Bullard couldn’t fathom telling his students that there’s a “silver lining in slavery.” He then took it a step further.

“Imagine the blowback of the same teacher trying to give you the upside of Nazi Germany,” said Bullard, now the senior political advisor of Florida Rising, a voting rights group in Florida. “Not only would it not be allowed, there would be bipartisan outrage over the idea that any teacher, a teacher or a curriculum trying to give the sunny side of Adolf Hitler. Yet we now have an African American history statute that is supposed to now give you this notion of the benevolent master, or the upside or benefit of being enslaved in America. It’s crazy.”

To Marvin Dunn, a man who has made a career off of keeping Florida’s Black history alive, most recently through his “Teach the Truth” tours, the issues with the new curriculum were plentiful. He called the “attempt to reach some sort of equivalency for racial violence in our history” flat-out wrong. He called the idea that enslaved people benefited from their subjugation “evil.” And he called the sparse mention of lynchings, which was only found twice in an explanation of guidelines, downright disrespectful.

“Your chances of getting lynched in Florida were greater than your chances of getting lynched in Mississippi and in Alabama,” said Dunn, professor emeritus at Florida International University. “They don’t even mention these incidents in any kind of substantive way in these plans and our students need to know that these things happen.”

Awakening Black parents

Dunn also questioned why students had to learn about “slavery in China, slavery in Asia, slavery in Africa” in a Black history course, something he saw as an an effort to show that “we were just another country that had slavery.” American slavery, however, was very unique.

“It was the only system of slavery in the world in which the people who were enslaved were defined as property, were reduced to chattel property,” Dunn said.

“For a Black child to sit in a Florida classroom and hear that their ancestors benefited from enslavement, how do you think” they will react? Dunn asked. “They are going to be hurt, they are going to be angry, they are going to tell their parents that this is being taught in the school.”

That, if anything, is the only positive takeaway from the situation: “These standards have awakened a sleeping giant that’s Black parents in this state,” Dunn said.

Etienne agreed, adding that she’s already in contact with many parents who have voiced their displeasure. She, for one, doesn’t have a choice but to abide by the new guidelines.

What she will do, though, is encourage her students to do their own research. To think critically. To answer their questions honestly.

“My plan is to give them as much information as possible so that they can make their own decisions,” Etienne said.

Reporting from the News Service of Florida contributed to this article.