'It takes a village': Why parents are joining their kids on the stage at graduation

As Yanelit Madriz Zarate crossed the stage at a University of California, Berkeley commencement ceremony this month, she reflected on the fits and starts in her educational journey: the mental and physical challenges that forced her to drop out after her first higher education stint in the California State system, the lessons she learned advocating for herself when she resumed at a community college and the empowerment she felt when she transferred to Cal.

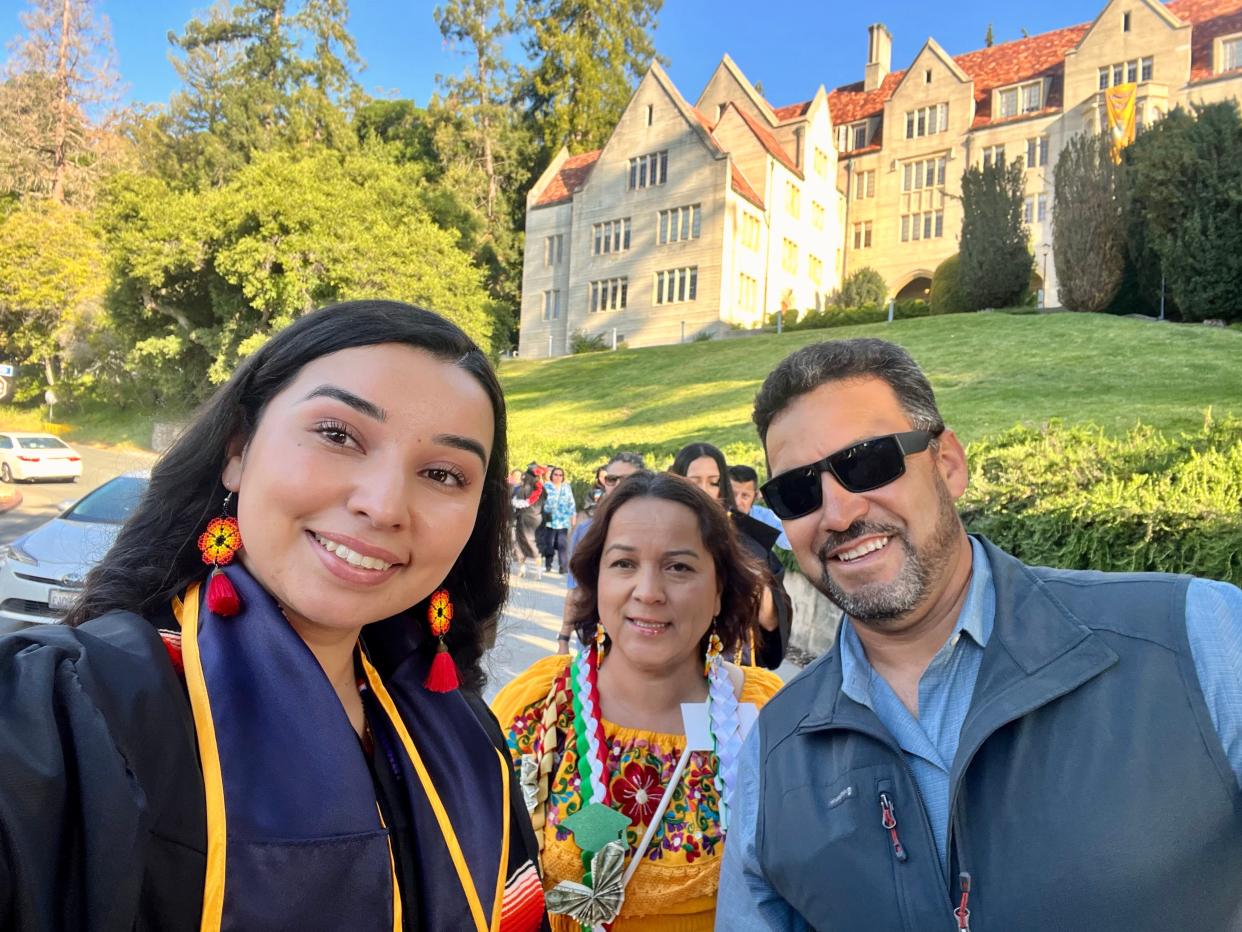

The 25-year-old also thought about the role her parents, immigrants from Mexico with just a middle school education, played in helping her get to graduation. So, it felt extra special – and extra fitting – that her parents got to join her on stage.

Crossing the stage with her loved ones, a decades-old tradition embraced in the university's Chicanx Latinx graduation, was something she looked forward to since she heard about the option years earlier. Madriz Zarate also made the moment her own: As her name was called out, she and her parents danced a zapateado, a traditional Mexican step.

“It was for the three of us,” said Madriz Zarate, a sociology major who grew up in San Pablo, California, and works part time in disability rights advocacy. “It feels like we’re finally being seen.”

Like Madriz Zarate, hundreds of thousands of graduates are the first in their families to attend college. The number of first-generation applicants is growing at more than twice the rate of students whose parents have a degree, according to Common App data.

However, many institutions of higher education have been slow to catch up. Surveys suggest mental health struggles are widespread among first-gen students, who often report they wish their campuses offered better support and academic and financial aid advising tailored to their circumstances.

While symbolic, the budding tradition of walking the stage with loved ones marks a shift in how colleges are engaging with students from nontraditional backgrounds and elevates the often-unspoken contributions of family members. It’s part of a larger trend of making graduation ceremonies more culturally relevant, in events such as Umoja graduations for Black students, Lavender events for LGBTQ+ graduates and blanketing ceremonies for Native students.

These special honors also stand as a reminder of what’s at stake when programs supporting such opportunities are restricted. Students at the University of Texas at Austin – whose funding for cultural graduation ceremonies was cut after last year’s diversity, equity and inclusion ban – had to raise private money this spring to hold the yearly Latinx event many had anticipated.

Affirmative action ban: After Supreme Court ruling, renewed focus on first-generation students

Graduation traditions evolve through DEI efforts

Cultural graduation ceremonies have grown in popularity, with events cropping up from Massachusetts to Hawaii. It’s all about “creating that sense of belonging and place on campus,” said Carolyn Barber-Pierre, the assistant vice president for student affairs and multicultural affairs at Tulane University in New Orleans. “So many students come with visible or invisible identities, and the fact that several of those identities can be celebrated means the world to them.”

Tulane hosts various affinity-group graduation ceremonies, and in some – like the Umoja event, attended by nearly half of the university’s Black graduates – family members can help place the stole on students. The stole is a cloth worn over the shoulders to represent campus achievements and cultural pride. Loved ones also have the opportunity to share reflections on the stage.

“This is the culmination of all the blood, sweat and tears for all the faculty, staff, parents and family members who’ve been there and helped each and every student succeed,” Barber-Pierre said.

“It takes a village, and the village was there.”

Gerald Thrush, the vice dean of academic affairs at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California, said family members’ involvement is often the highlight of graduates’ commencement. Since the medical school’s early days more than four decades ago, it’s allowed students to bring two family members on stage to bestow their academic hood. The hood is similar to the stole but instead drapes down the graduate's back.

When students shake the president’s and dean’s hands during the first part of the stage procession, they’re often visibly nervous, Thrush said. But as soon as they see their loved ones nearby, their eyes light up.

“Just seeing the pure joy and the excitement of the family … it’s such a heartwarming, touching moment,” said Thrush, who serves as the commencement marshall and has witnessed the exchange countless times over the years. “You can see it – you can see that support there.”

Lezlye Ramos, who recently graduated with a doctorate in occupational therapy from the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, in California, brought her dad on stage to walk with her and place the hood on her shoulders. Wearing a tejana hat and boots, her dad, who works in construction, was worried about how he'd come off. But he ended up stealing the show, said Ramos, 26. After she posted the video on social media, she was flooded with comments from fellow Latinx students who shared how inspiring it was to see the interaction.

“Being able to see someone who looks like you, to see the diversity within higher ed … it struck me that this is something bigger because of what it represented,” she said. “Although my name is the one on the diploma, we all graduated that day.”

'An inversion of the graduation'

UC Berkeley started the stage-walking tradition with its Chicanx Latinx graduation several decades ago, according to Pablo Gonzalez, a Chicano scholar at the school who has emceed the event. “Even though graduations are often viewed as individual achievements, in this particular case, the collective achievement is celebrated,” he said. “It’s about acknowledging more than yourself.”

Gonzalez isn’t aware of many other colleges offering this opportunity.

Gonzalez recalled being in the crowd as his uncle, the first in their family to attend college, walked across the Berkeley commencement stage with Gonzalez's grandparents. He remembers witnessing his brother also participating in the family rite. Both experiences helped him envision his own higher education future. Gonzalez himself participated in the tradition as a Berkeley graduate in the late 1990s.

He described the stage-walking tradition – and other aspects of the Chicanx Latinx event – as “an inversion of the graduation.” Traditional commencements focus on the graduate while this one “focuses on the people who are crucial and central to their success."

"That kind of inversion is such a powerful marker of community that’s so necessary right now,” he said.

It's happened before: College graduation canceled due to anti-war protests?

For Kayanna Harris, another Berkeley Class of 2024 grad, the inverted approach to celebrating her accomplishments was “humbling.”

Harris, now 32, moved to the U.S. from Jamaica after finishing high school. She opted not to attend nursing school where she grew up, leaving her parents behind. She spent a few years in New York, where some of her siblings live, but consistently felt a pull toward California – and specifically Berkeley. At 25, she finally settled in the area, enrolling in a community college. A few years later, she transferred to UC Berkeley – the college of her dreams, as an aspiring chemical engineer.

Harris is undocumented and has faced a host of challenges beyond those of being a first-generation student. Financial aid options were limited. She struggled to get internships because of her immigration status and couldn’t study abroad. Nor could she return to her homeland to visit her dad, a former farmer whose leg was amputated a few years ago, and mom, who worked at home, caring for Harris and her eight siblings.

Harris felt the smaller graduation ceremonies – including one for undocumented students and one for Black students – were the most important, largely because the family participation was baked into them. In the UndocuGrad event, she walked with her mom and sister as other relatives and friends cheered them on. (Her dad couldn’t make the trip because of his mobility issues.)

“It was really a sense of gratitude to know that, even though they were all the way in Jamaica, they’re always there. They’re always behind you. These people are the ones motivating you to move forward,” she said. “That big smile on (my mom’s) face is really what I wanted to see. I wish that moment was a moment that lasted forever.”

Madriz Zarate will always cherish her moment, too. Part of her self-advocacy journey involved reconnecting with her culture through dance. That’s why it was so important for her and her parents to zapatear – a dance style where the feet rhythmically strike the floor – as they crossed the stage.

“It felt like we were creating a safe space not just for ourselves but for other folks to dance – it’s a very liberating and healing part of our culture, “ she said. As they stomped across the stage, surrounded by families with similar lived experiences, Madriz Zarate felt validated.

“It was like creating magic.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Why are parents walking with their kids across the commencement stage?