Surviving gun violence does not end victims’ pain and trauma

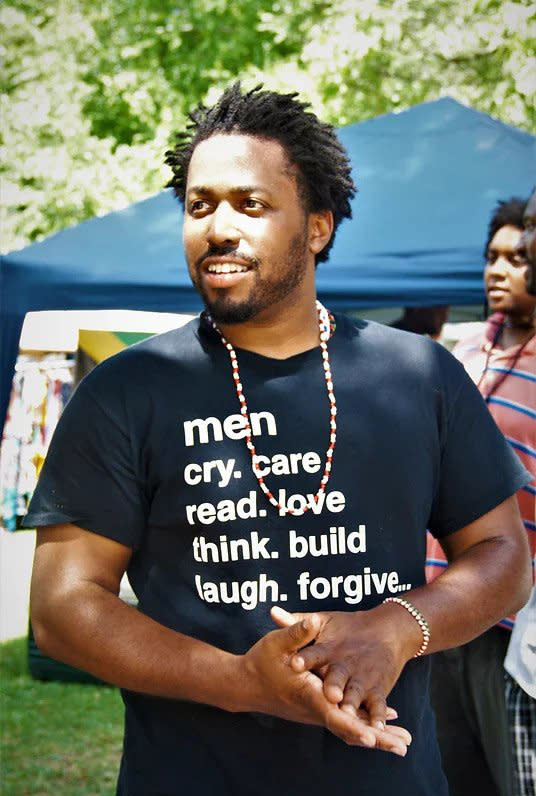

In March 2020, Devon Gipson was shot five times in a drive-by shooting two houses down from his grandmother’s home in South Los Angeles. The mother of his daughter was shot in the leg, and a friend was killed.

Gipson, who works stocking supplies at a contractor warehouse, considers it a miracle that he survived the gunshot wounds to his shoulder, back, arm and body. As he recovered, Gipson learned that healing physically was only a small part of the process.

A few months after the shooting, he started becoming paranoid about his surroundings and couldn’t sleep. He also said watching a scene of a drive-by shooting on television gave him an unexpected reaction.

“And I was fine at first,” Gipson, 35, recalled. “And then I started having a panic attack. I couldn’t breathe. So, I got up and went outside to try to get some air. I was walking in circles, like a dog trying to catch its tail. It felt like I was struggling to breathe for two hours. In reality, it was about 15 or 20 minutes. I was like, ‘Oh, man. I’m still in that moment that happened to me.’”

Although data shows gun violence is down 4% from last year, that violence still disproportionately affects the Black community. Gipson’s reaction to being shot, like many others in the Black community, isn’t uncommon. His trauma speaks to the dire need for post-care counseling and the importance of it in cities experiencing gun violence.

Hospital programs like Healing Hurt People in Philadelphia — where 84% of the victims of gun violence are Black, according to the city’s Office of the Controller — and Chicago’s Shirley Ryan AbilityLab are dedicated to providing psychological aftercare to victims of gun violence.

It is an area that psychologists say gets too little emphasis, considering the high number of gunshot-wound survivors. For every gun-related homicide, there are more than two nonfatal gun shootings, according to the Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence. It also says that 9 in 10 survivors of gun violence experienced trauma from being shot. Additionally, the data shows that residents of the poorest neighborhoods are 6.9 times more likely to be victims of gun violence than those in better-off areas.

That trauma manifests itself in post-traumatic stress symptoms, including insomnia, depression, nightmares or flashbacks, alcohol or substance abuse, and an inability to concentrate, among others.

Gipson can attest. When he is able to sleep, he dreams about the shooting, and he often finds himself experiencing manic moments where he finds himself studying “the way people walk, the way people look, where they put their hands.”

While Gipson has not sought counseling and considers himself “OK,” despite the occasional nightmares, anxiety and paranoia, he acknowledges that there is an increasing need for programs that can specifically address issues like his.

Why programs like Healing Hurt People are needed

If Gipson had been shot in Philadelphia and gone to Drexel University Hospital, counselors from Healing Hurt People, a free intervention program that operates during emergency room hours between 9 p.m. to 2 a.m., would have been able to address his physical needs. The program identifies and addresses a victim’s trauma through interviews, said Dr. John Rich, the author of “Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Trauma and Violence in the Lives of Young Black Men,” and one of the founders of the program, along with Dr. Ted Corbin.

“We want to change the conversation . . . toward healing and strength,” Rich said.

The Healing Hurt People team consists of a program manager who is a clinical social worker, two social workers and a pair of intervention peer specialists who have gone through the program. Together, they identify victims of gun violence and offer them “trauma therapy,” which includes behavioral counseling, youth assessment and other social-work-related services to help patients heal from their trauma. This includes making home visits and group counseling.

The program’s intervention peer specialists also provide victims with on-site counseling, which is critical because the peer specialists are gun violence victims themselves and therefore can relate to the victims, providing real-life assessments on how to cope with being shot.

Jermaine McCorey, 32, went through the program. He was shot three times in 2010, and again in 2012. Healing Hurt People counseled him after the second shooting as he lay in his hospital bed. He worked his way through the program, eventually becoming an intervention peer specialist for two years.

“After I got shot, I was going through depression,” McCorey said. “I had a feeling of hopelessness. I wasn’t able to sleep much. I was withdrawn, and if I closed my eyes I saw gunfire.”

McCorey said the program has changed his life. “It’s been invigorating to come out of all that,” he said, adding that the psycho-educational group sessions helped him to understand that he wasn’t the only one going through this. “So now, to help others, it’s truly empowering,” he added.

At Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago the approach is similar. The program, which has been ranked as the No. 1 hospital rehabilitation center for 32 consecutive years by U.S. News and World Report, offers a robust physical therapy component that addresses the needs that come with traumatic injury. And its area of mental rehabilitation is just as strong and important, Jenna Sarna, manager of psychology/patient family counseling of the AbilityLab, said.

“Emotional distress is not always as visible as the physical injuries can be,” she said. “But it can be equally painful and impacting. So, part of our goal is to help these individuals, both physically and emotionally, with their rehab needs, through our interdisciplinary team.”

She added that many gunshot survivors — including young Black men– have never received counseling of any sort, so she wants them to “see the value of possibly seeking treatment after they discharge from our organization.”

Like the patients, Rich, Corbin and Sarna see the value in these types of treatments and are concerned that not enough hospitals have created similar programs. The Healing Hurt People founders hoped their program would be duplicated around the country. However, that hasn’t been the case. Even though Healing Hurt People (HHP) and AbilityLab are funded by grants and donations, there seems to be a stall in getting these types of programs started into hospitals. So far, Portland’s Cascadia Health and The University of Chicago Hospital have adopted HHP. But, Corbin said, more programs are needed because “we’re putting these hurt people right back into the community from where they came and sustained injury.”

Obari Cartman, a psychologist who has treated gunshot victims in Chicago, said he is not surprised that psychological counseling is not widely available for shooting survivors. He added that the focus of local officials tends to be on gun control and police budgets rather than “healing for community safety.”

“There’s a sense that if we can lock them all up and get rid of them that everything will be OK,” he said. “So, the priorities are skewed.”

To him, gun violence extends beyond the victim. “It’s also the bystanders, the vicarious trauma they suffer witnessing the shooting,” Cartman said. “Shootings impact the whole psyche of the community. There’s a lingering loss of safety, not just for the victim, but all who live where it happened, persistent anxiety and a constant feeling of having to watch your back. It can really have long-term consequences.

Sarna said that having more programs like the AbilityLab would be beneficial to countless people, as the process of helping a survivor of gunshot violence is rewarding for all involved.

“It’s amazing watching their journey while they’re going through the treatment,” she said. “We get to help support them and give them coping strategies and help them find ways to process or to de-stress or to reduce that physiological arousal and partner with them and kind of walk them through it. … And it can be a long journey without therapy.”