A Strange Creature Was Lurking in West Virginia. Then an Iconic Bridge Collapsed

A sleepy town of barely 4,000 people, Point Pleasant sits on the north bank of West Virginia’s Kanawha River, where it empties into the Ohio River. A single, family-run hotel and smattering of local restaurants and fast food joints greet the traveler. It feels, for the most part, indistinguishable from many rust-belt towns: lush with greenery and open park spaces, punctuated by derelict buildings and businesses with a sense that life has passed it by.

But for one weekend in the early fall, Point Pleasant hosts the annual Mothman Festival, celebrating the region’s homegrown, enigmatic cryptid: a flying humanoid with glowing red eyes burning out of its chest.

The 2022 festival is massive, with an estimated 15,000-plus attendees. Some wear elaborate cosplay getups, others are in Mothman T-shirts (one reads “Live, Laugh, Lurk,” while many others are lewder, Mothman having become something of a sex symbol in this world of mythical creatures). Booths line the streets selling stickers, hot dogs, and funnel cakes. Amateur ghost-hunting crews sit at recruitment tables, and half a dozen authors are hawking their self-published books on any number of paranormal themes. The coffee shop has brought out its plywood face-in-hole board for patrons to pose as Mothman for photos, while, down the street, one vacant store has been converted into a makeshift lecture hall where speakers are giving talks on topics including “Flying Monsters” and “Top Ten Cryptids.”

Authors Bill Kousoulas, PhD, and his wife, Jacqueline Kousoulas, round out the first day of activities with a discussion of their research into Point Pleasant and Mothman. At one point, Bill says to the crowd, “It’s nice to see so many people out here for today’s celebration,” but then immediately corrects himself: “It’s not a celebration.”

“One of the reasons we’re all here today,” Bill says, “is because of that bridge collapse.”

The Silver Bridge opened on May 30, 1928, to much fanfare. Officially the Point Pleasant Bridge—it earned its nickname from its silver aluminum paint—the eyebar-suspension-chain bridge connected Point Pleasant, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio. It was breathlessly advertised as an entirely new, sturdy cantilever design, demanding “worldwide attention.”

A dedication ceremony on its opening day began with a parade of decorated cars, followed by speeches from West Virginia’s governor and Ohio’s lieutenant governor. Miss Point Pleasant walked onto the bridge from the West Virginia side, to be met in the middle by “a young French gallant” representing Gallipolis for a handshake.

An estimated 10,000 people crossed the bridge on the first day it opened to the public, eager to be a part of history. The novel design principles seemed to prove themselves sound, and a second structure—the St. Mary’s Bridge—was built later that year, 75 miles upriver, using the same construction.

For much of its existence, Point Pleasant had been at the mercy of the Ohio River—its economy was based around the ships that navigated its waters, those same waters that regularly flooded the town. One of its largest employers was the shipbuilder, Marietta Manufacturing Company. The bridge connected Point Pleasant to the world beyond the river, making it a thoroughfare between the state capitals of Columbus and Charleston. And with a link to a major interstate artery, U.S. Route 35, the town’s population nearly doubled and new businesses, including a multimillion-dollar resin factory, arrived.

As the region grew, traffic increased and vehicles evolved. When the Silver Bridge opened, a Ford Model T weighed about 1,500 pounds; by the 1960s, cars often weighed closer to 4,000 pounds. At its peak, the bridge saw an estimated 4,000 cars and trucks cross daily—an amount that ultimately proved to be too much for the bridge to handle.

Just north of Point Pleasant sits the McClintic Wildlife Management Area, over 3,600 acres of wetlands and forest. A popular destination for hunting, fishing, and trapping, it is lush and overgrown, with lakes that glow a vibrant green from algae. McClintic Wildlife is also home to a series of abandoned concrete domes, 20 or so feet in diameter, 10 feet high, emerging from the ground like alien igloos. This had once been federal land, and during World War II, these structures were used to store stockpiles of TNT, built apart from one another to ensure that any accidental detonation didn’t destroy the whole area. After 1946, the federal government turned it over to the state for a nature preserve, and in the postwar years, it grew feral.

On November 12, 1966, just before midnight, two couples driving through the reserve saw a mysterious figure. It was six or seven feet tall. It had wings. And it stood upright, like a man. The creature lacked a visible head, but two glowing eyes in its chest stared at them before it flew off.

More sightings poured in. One witness, Connie Joe Carpenter, described it as “horrible…like something out of a science-fiction movie.” Thomas Ury saw it while driving on the morning of November 25. “It came up like a helicopter and veered over my car,” he said.

After the initial reporting hit the newspapers (4 More Say They Saw Red-Eyed ‘Whatever,’ ran one such headline), experts rushed in to calm the furor, dismissing the sightings as nothing more than a regular bird. “There is no doubt in my mind that the ‘strange monster’ or ‘large terrifying bird’ or what have you was a sandhill crane,” Robert L. Smith, an associate professor of wildlife biology at West Virginia University, told reporters at the time. A crane, he explained, can stand up to four and a half feet tall, with a wingspan over seven feet. Like many animals, its eyes can appear to glow when caught in headlights, and, when startled, the bird sometimes extends its wings.

But Smith’s naysaying did little to quell the growing fervor; within days, hundreds of sightseers jammed the country roads of Point Pleasant, hoping to get a glimpse of the red-eyed whatever. Nineteen sightings were reported between November 12 and December 11, before trickling off. The last reported sighting was January 11, 1967, when Mabel McDaniel saw a large, winged creature on Route 62 flying over Tiny’s drive-in restaurant.

Linda Lane was 18 in 1967. She had just graduated from high school that year and was still living at home in Gallipolis, just across the river from Point Pleasant. On the afternoon of December 15, she left the house with her mother around 4:30 to buy groceries, when emergency vehicles began streaming past her—“Never seen so many in my life!” she’d later recall to the authors Bill and Jacqui Kousoulas.

At first, her mother thought that there had been some kind of car accident on the Silver Bridge. But when Linda looked toward the bridge, she saw nothing.

“Where’s the bridge?” she cried. “Where’s the bridge?”

The Silver Bridge, engineering marvel of the Ohio River valley, was gone.

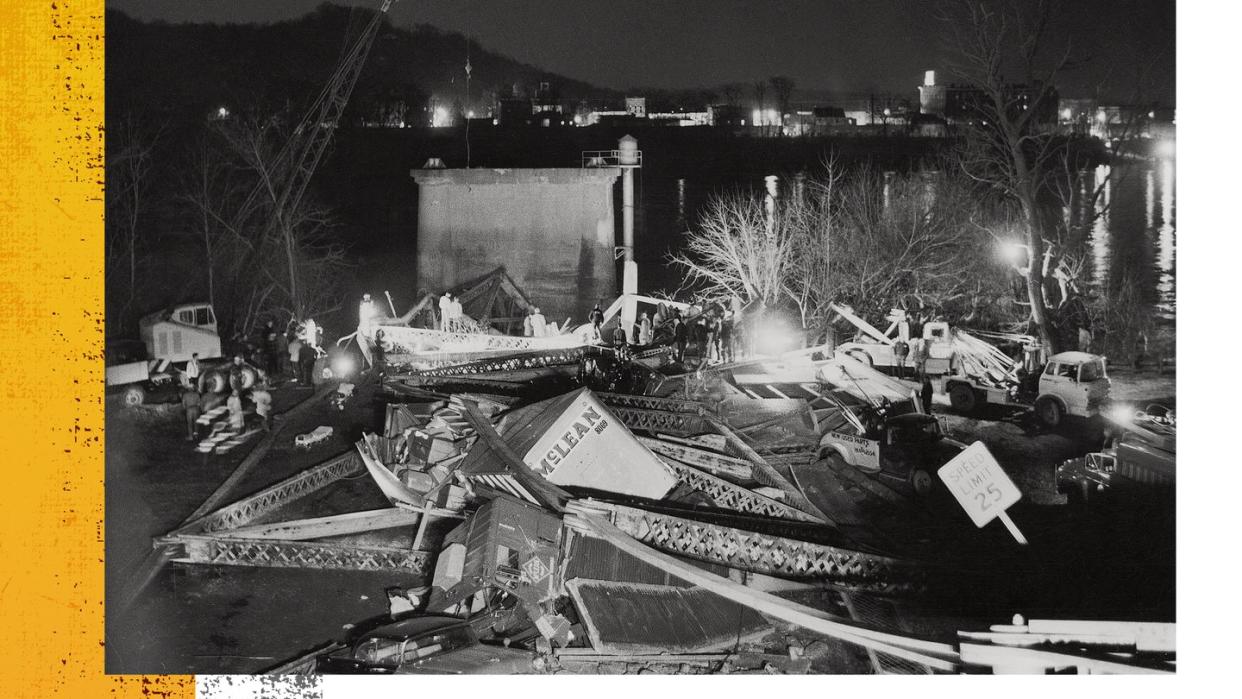

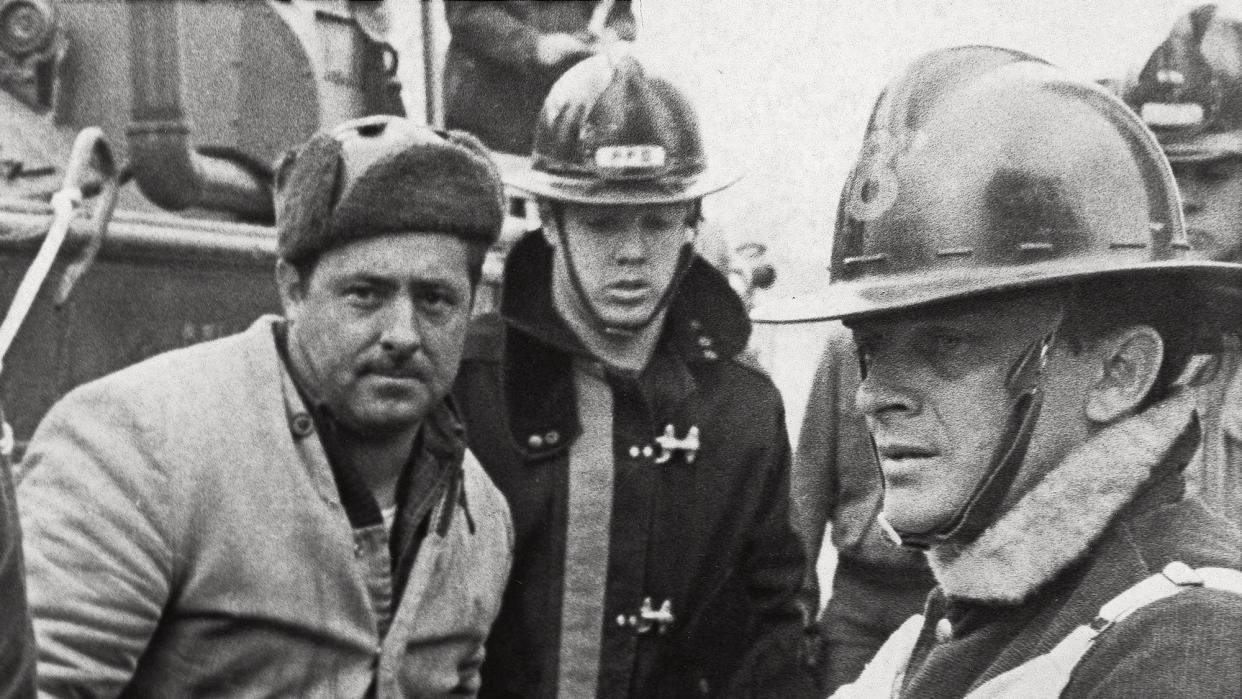

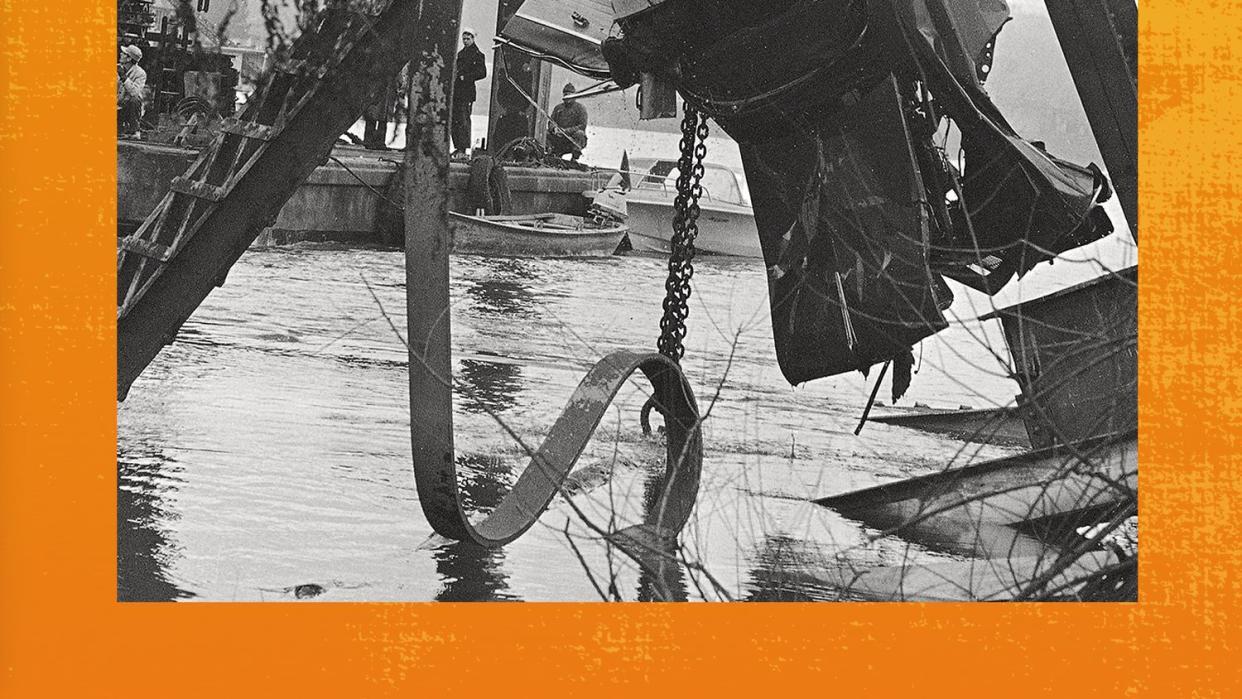

The destruction was catastrophic. “It didn’t just fall into the river,” a coal truck driver told the Charleston Daily Mail the next day. “It sort of slithered like a snake, then it buckled and cars began falling off sideways.” Charlene Foster, another witness, further described the scene: “It was like a chain reaction,” she said, “It did not fall all at once. My God, it was horrible.” As the Silver Bridge collapsed into the Ohio River, it took with it dozens of cars and at least three trucks, ultimately claiming 46 lives.

The collapse severed the economic lifeline in and out of the region. The federal government estimated that the time and fuel used to reroute traffic around the collapsed bridge totaled $1 million a month. Interstate commerce to the local businesses in Galli-polis and Point Pleasant evaporated. The two cities, which had been linked for decades, were now connected only through an ad hoc ferry system, cleaving the micropolitan area in half.

As the economic damages mounted, President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized federal funds to rush a new bridge through, and the Silver Memorial Bridge, opened two years later. But the new bridge bypassed Point Pleasant. Route 35 no longer ran through town. A major local employer, the Marietta Manufacturing Company, closed down in 1970.

When National Transportation Safety Board investigators recovered the wreckage, much of what they found was covered in rust. But they homed in on one small piece where the rust ran much deeper, the metal far more corroded: a single eyebar, originally positioned on the upstream side of the bridge, had snapped in two. It was as though a crack had developed over time, a slow corrosive fissure.

The innovation behind the Silver Bridge had largely been driven by cost-cutting measures, as the group in charge of reviewing potential designs offered a bonus to any company that could keep costs under $800,000. As a result, the bridge had an unorthodox construction.

Where suspension bridges like San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge use woven-wire cables to span their length, the Silver Bridge was suspended from heat-treated steel eyebar chains that looked like elongated links of a bicycle chain, each two inches thick, ranging in length from 44 to 55 feet.

This method had been used only once before, on the Hercílio Luz, a bridge in Brazil that was built by the same company. But the Hercílio Luz relied on four eyebar chains; the Silver Bridge, using a new, mostly untested heat-treating method to increase the strength of the steel, used only two chains.

In addition to support, bridges need some kind of stiffening truss—or framework of interconnected beams—to keep the structure rigid. The truss for most bridges is supported independently of the suspension; in the Hercílio Luz, for example, a network of cross girders—a different kind of support-beam structure—beneath the roadway stabilizes the bridge’s truss.

With the Silver Bridge, however, the suspension chains hanging from the eyebars were also used to support the top of the bridge’s stiffening truss, a feature that added extra strain on the suspension cables. At the time it was built, it was the longest bridge—1,460 feet, including its side-spans—suspended and reinforced in such a fashion.

The novel design proved to be no match for the Ohio River Valley’s humid summers and frigid, icy winters, nor the repeated cycles of stress from increasingly heavy bridge traffic.

Meanwhile, the design of the eyebars prevented inspectors from seeing warning signs. And even if they had, it would have been no use. Once the bridge was built, there was no way to make any “adjustments in the chains, hangers, or trusses,” the Engineering News-Record noted during the bridge’s original construction. The initial crack was barely one-quarter-inch long. But once it formed, all it could do was grow.

Investigators came to understand that this single, tiny flaw destroyed the entire bridge. Had the bridge used two pairs of suspension chains, as the Hercílio Luz does, it might have survived. But without any redundancy in its design, the crack was catastrophic. (The St. Mary’s Bridge upriver was closed, dismantled, and replaced once it became clear that it had a similar design problem.)

The Silver Bridge collapse not only changed Point Pleasant, but also American infrastructure. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1968, passed in the wake of the disaster, created the first national bridge inspection program, requiring that all bridges constructed with federal funds receive an inspection every two years.

But safer bridges could not bring back the dead, and long after the bodies were recovered and the wreckage cleared away, the damage of that day lingered, leaving the community looking for a way to make sense of the tragedy.

During the initial Mothman sightings of 1966, paranormal investigator John A. Keel traveled to Point Pleasant to interview witnesses, some of whom believed that Mothman was some kind of UFO. But after the bridge collapsed, he suggested that the Mothman sightings were a form of prophecy, portending the bridge’s failure a year before it happened—a warning that went unheeded.

In 1975, Keel published a book, The Mothman Prophecies, which became a cult classic and, in time, breathed new life into the myth of Mothman. What’s more, it gave a narrative to a traumatic event. The book connects the original sightings with a series of otherworldly phone calls that Keel claims he received, offering cryptic predictions.

The popularity of Mothman exploded again in 2002, when a film based on the book came out, heavily featuring the Silver Bridge, starring Laura Linney and Richard Gere. The movie, while only a moderate success, put Keel’s book on the New York Times bestseller list. It also led to an influx of tourists, and a longtime Point Pleasant resident, Jeff Wamsley, saw an opportunity. He helped found the annual Mothman Festival, the first of which was held that year.

In 2003, commissioned by a Point Pleasant commerce group, the late Bob Roach, a local welder, installed a Mothman statue. The figure—silver like the bridge—has veiny wings that rise 12 feet in the air; its open mouth bares four jagged teeth that, with its red eyes and clawed hands, looks like it’s hissing at visitors.

Tourists flocked, and just a few years later, in 2006, Wamsley opened the Mothman Museum. Visitors who walk into the museum are met with a lifesize Mothman replica. It’s flashing a toothy grin with its hands crossed in front of its stomach, holding up two fingers, like peace signs. And this is just the first of two replicas; the other is covered in feathers, and it stands next to a poster that poses the question: “Who or what was the Mothman?”

The original police depositions and news coverage from the first Mothman sightings are preserved in the museum, as well as sections of steel from the original bridge. The museum leans into the outsized mythology behind Mothman, with displays dedicated to Keel and others who have written about the cryptid, as well as artifacts from the 2002 movie.

Above all, the museum implores visitors to “research and uncover the truth yourself.”

Without the bridge disaster, Mothman does not really exist. It’s more likely that there would be nothing but a series of sightings receding each year into the distant past. But to Mothman fanatics, the collapse and the lore behind it open up vertiginous questions about how the universe really works.

And likewise, without Mothman, it’s possible that we would have forgotten the lessons of bridge safety ushered in by the Silver Bridge collapse. Given the national attention it received at the time, and the subsequent safety regime implemented, the Silver Bridge should have been the last major bridge failure in America. But it wasn’t. As civil engineer Henry Petroski writes in his book To Forgive Design, regulations are not enough to prevent disaster. It is imperative that we keep alive the memory of disasters, and recall that they can even happen to engineering marvels.

Even at the festival, disaster lurks in the background. Cryptid sightings have sometimes been used by local communities to drum up tourism, most famously Loch Ness in Scotland, with its Nessie. Other places—usually small, out-of-the-way towns—used cryptids as local mascots, a means of establishing an identity. The region around Lake Champlain has its Champ, for example, and Western Canada has its Ogopogo. But Mothman is unique in that, to some of its fans, the creature invokes a sense of unease the past is unfair, the world is out of balance.

When people start to discuss what they think Mothman really is, theories suggesting high-level malevolence come spilling out. One festivalgoer says she believes Mothman is likely a government experiment that escaped—a theory echoed in fringe guidebooks and blogs that allege a secret “labyrinthine” lab under the TNT area.

It’s typical talk from conspiracy theorists: puzzling and vague accusations of malfeasance. It often comes from people who have a general sense of distrust toward their environment. They can feel, on some level, that something is not right, but they can’t quite put their finger on what. Sometimes, communities that have faced tragedy search for narratives that will help make sense of what has happened to their land, says Wanda Addison, a folklorist at National University in San Diego.

The feeling isn’t necessarily misplaced. After all, the Ohio River is one of the most polluted rivers in the country; tens of millions of pounds of chemicals are dumped into it each year. Projects from a local chemical company have left hundreds sick or dead from silica poisoning and a gas leak. Point Pleasant’s population has been in steady decline for the last 50 years; it’s lost nearly a quarter of its people just since 1990. It can feel as though the land itself—emptied, strip-mined, and polluted—has become uncanny.

Meanwhile, Mothman has become a major tourist attraction in Point Pleasant, providing a vital economic boon to the area, according to a 2015 study in Southeastern Geographer. “It’s helped the town,” local hotel owner Ruth Finley told the Toronto Star. “People come because of Mothman and they stay at the hotel, they go to the restaurants.”

If Mothman’s legacy depends on the bridge, the bridge’s legacy is helped in turn by Mothman. The 1967 collapse was a turning point in American infrastructure. But Petroski argues that the “technological memory of any industry” only tends to last about a generation; after that, he says, vital lessons are forgotten and disasters can

happen again.

It is the cryptid hunters, the paranormal enthusiasts, and the Mothman cosplayers who help keep the memory of the Silver Bridge alive in popular imagination. Myths like Mothman, the things that revitalize stories of tragedy, Petroski says, can remind us not just of successes, but also of failures. And that can help future engineers and developers avoid blind spots of the past so that they can more safely pursue bold, complex ideas.

You Might Also Like