After storms, Miami-Dade’s low-income residents suffer. New ‘hubs and pods’ may help

After Hurricane Irma crashed through South Florida in 2017, community leaders and elected officials got a first-hand look at the long list of things Miami’s most vulnerable residents needed to get their lives back on track.

There were horror stories of elderly residents equipped with only “tuna and a flashlight” ahead of the storm, SNAP benefits not working at grocery stores after power outages and diabetics left with no way to cool their insulin.

READ MORE: Some health risks from climate change in Florida may surprise. This one affects millions

Now, those communities have a new chance to be a part of designing “resilience hubs” of the future. In this case, that involves retrofitting some government buildings to better serve residents before — and long after — a storm.

On Monday, the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center announced a million-dollar state grant to make plans to beef up three “hubs” of resilience in Miami-Dade’s underserved communities.

“They’ll provide safety, education and materials to make these disasters as manageable as possible,” Miami-Dade Mayor Daniella Levine Cava said at a press event announcing the grant. “We’re going to make our communities safer.”

Rick Miller, deputy director of Arsht-Rock’s Resilience Hubs Initiative, said the yearlong process will include an extensive study of the climate and social vulnerabilities in Miami-Dade, as well as more than a dozen community events to crowdsource ideas for what the future hubs could do.

Some ideas include adding solar panels and battery backup, so these spots stay functional when the lights go out, or stronger WiFi networks. At the end of the year, the million-dollar process will produce a guidebook on what kinds of services are needed in different parts of the county.

“Resilience is about more than just building stormwater pumps and bigger pipes, it’s about people,” Miller said.

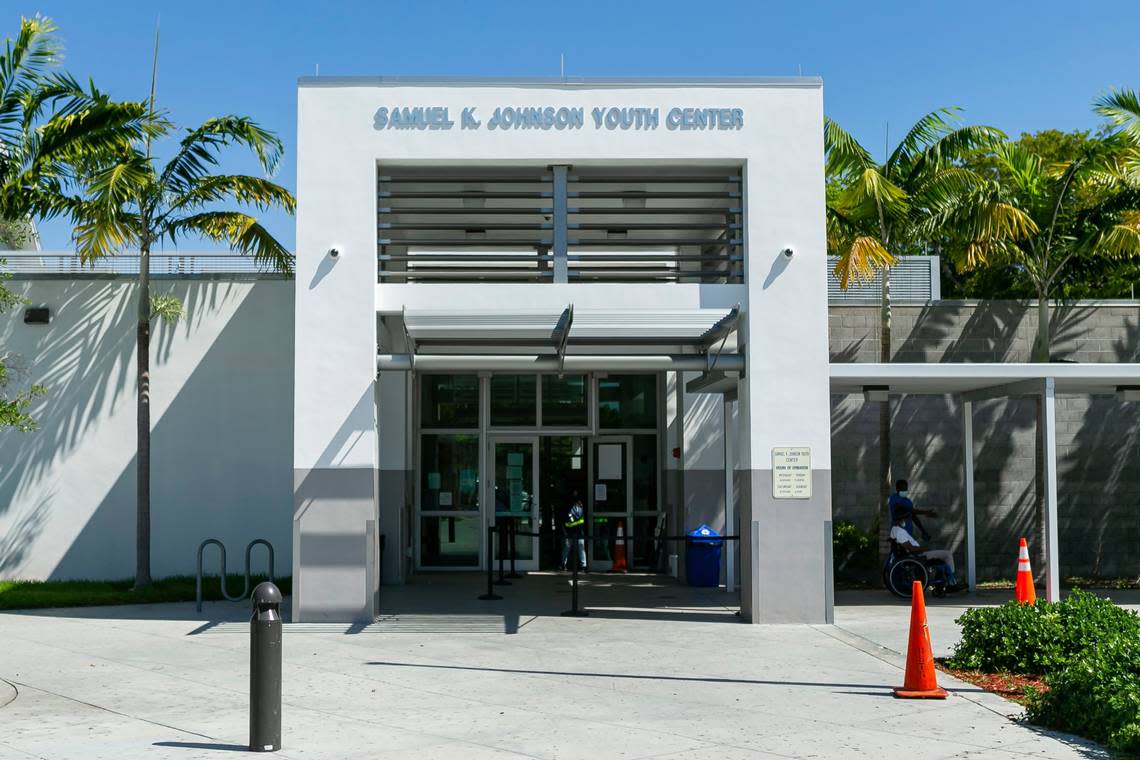

This plan focuses on three hubs, which are existing municipal buildings like libraries and community centers, but Miller envisions a future network of even more hubs, along with mobile units called pods that can be deployed after a disaster. The pilot “resilience pod” Arsht-Rock currently displays is a solar-powered WiFi hot spot filled with educational materials about climate change in South Florida.

Hardening existing community buildings has long been a goal in Miami-Dade, and it’s already happening.

The city of Miami recently received a more than $750,000 federal grant to add impact windows and doors, as well as a generator, to the Carrie P. Meek Senior Center at Charles Hadley Park. The grant will also fund a better WiFi network and an expanded charging area to the center, which regularly serves as a food distribution center for the neighborhood.

“This will be our first premiere resilience hub,” said Alissa Farina, Miami’s assistant chief resilience officer.

Farina said the city learned in Hurricane Irma’s aftermath that its residents needed goods and services everywhere in the city, not just at a handful of spots.

“The roads are impassable; people don’t have cars, they don’t have gas, they don’t have money,” she said. “We’re trying to bring everything to them, to places they know and trust.”

While this planning effort is underway, the same community-based mutual aid efforts that sprung up after Irma are still going strong, creating some tension between the city’s grassroots activists and the nonprofit that just secured a hefty grant.

Some Miamians only had ‘tuna and a flashlight’ after Irma. There’s a plan to change that.

“This is what we’re already doing,” said Michael Clarkson, founder of Little Haiti-based community support group Konscious Kontractors. “Why aren’t we a part of this?”

Clarkson was part of the group of local nonprofits that went door-to-door checking on folks after the storm, providing them services and resources in a project that eventually evolved into the Community Emergency Operation Center.

The CEOC now has a formal seat at the county and city Emergency Operations Center when a disaster is ongoing, and its members still meet every Saturday for community giveaways and events.

“We provide services and hope. That’s the most important thing,” Clarkson said. “The Miami of the future depends on the ideas and the will of the people.”