Stillwater Washington’s state championship impacts alumni 68 years later. 'It lives on'

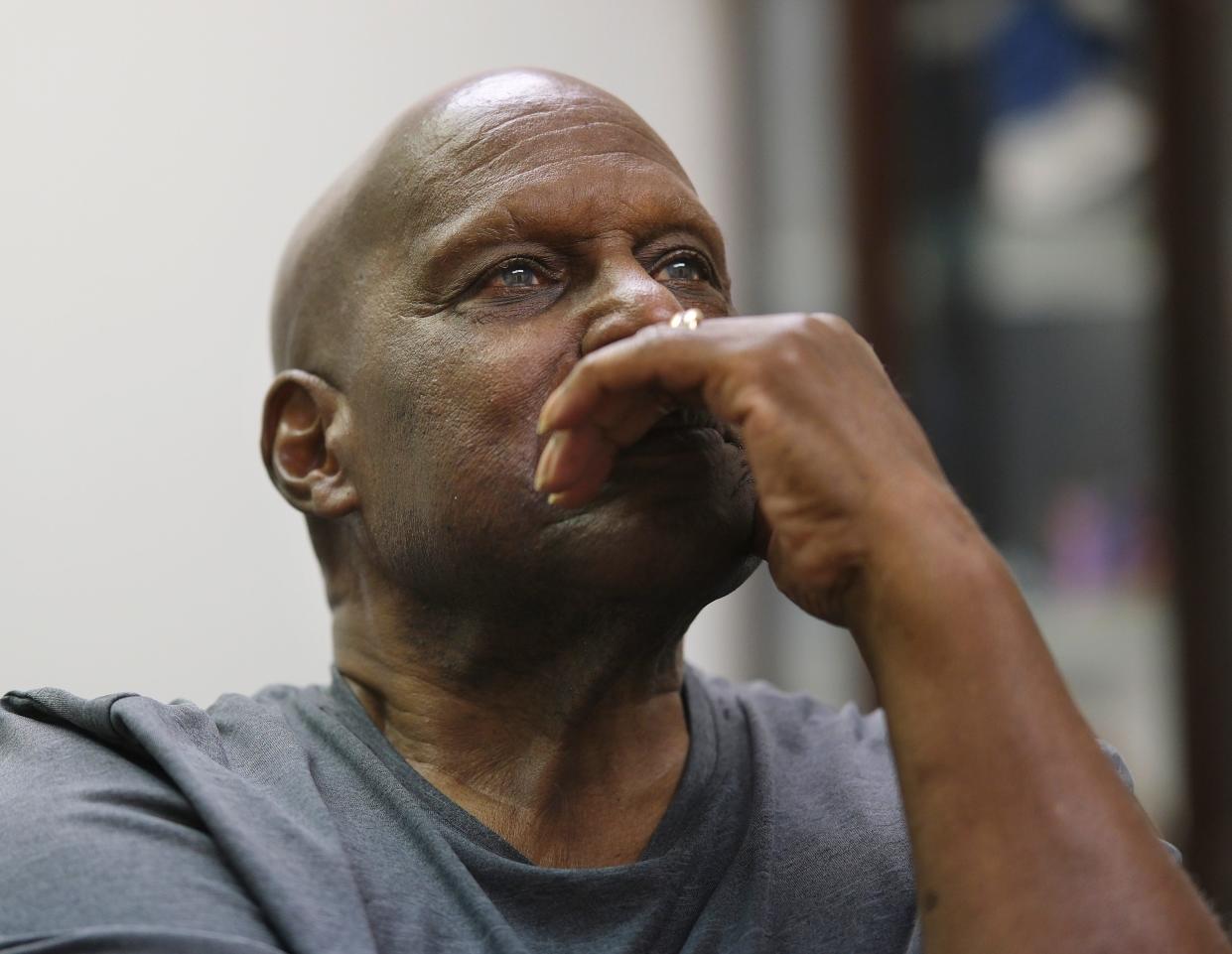

The Rev. James E. Reed Sr. pointed to a newspaper clipping and mentioned each leader with admiration.

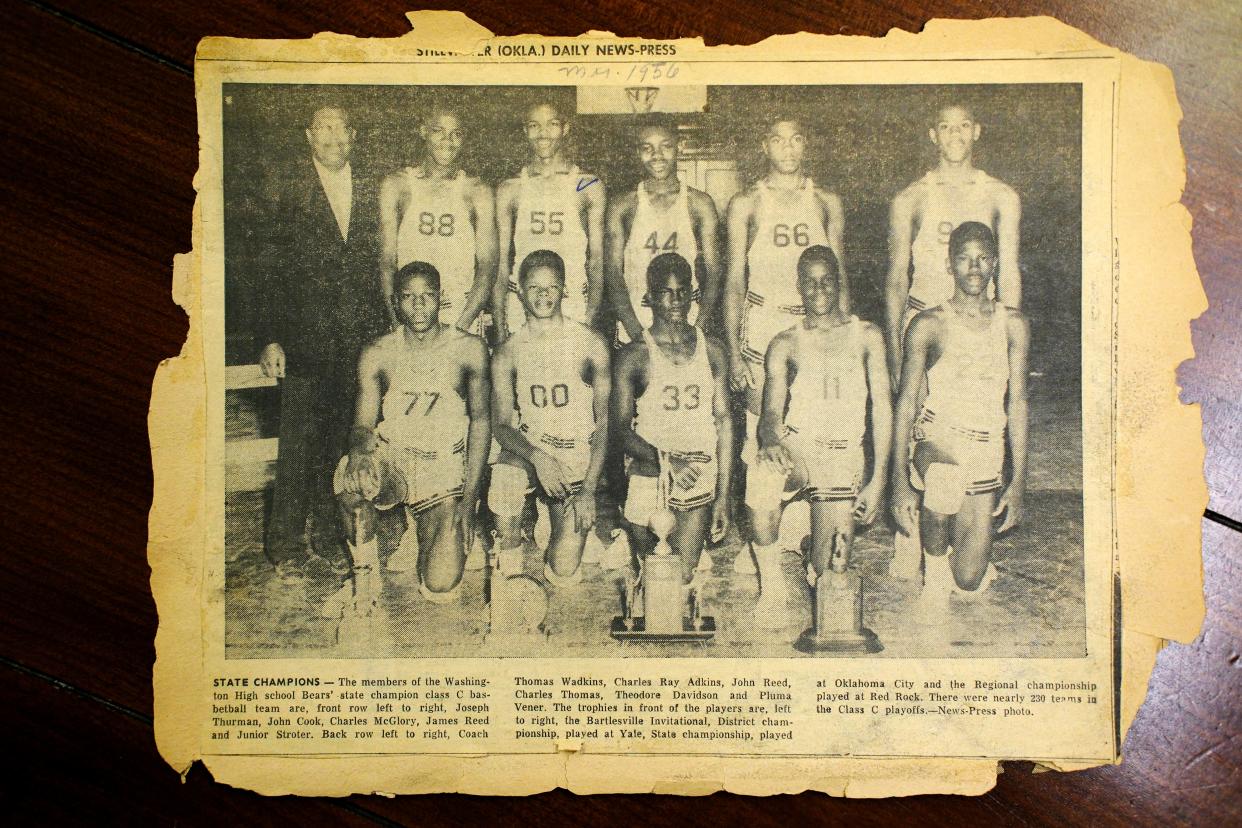

John Reed. Charles Adkins. Thomas Wadkins.

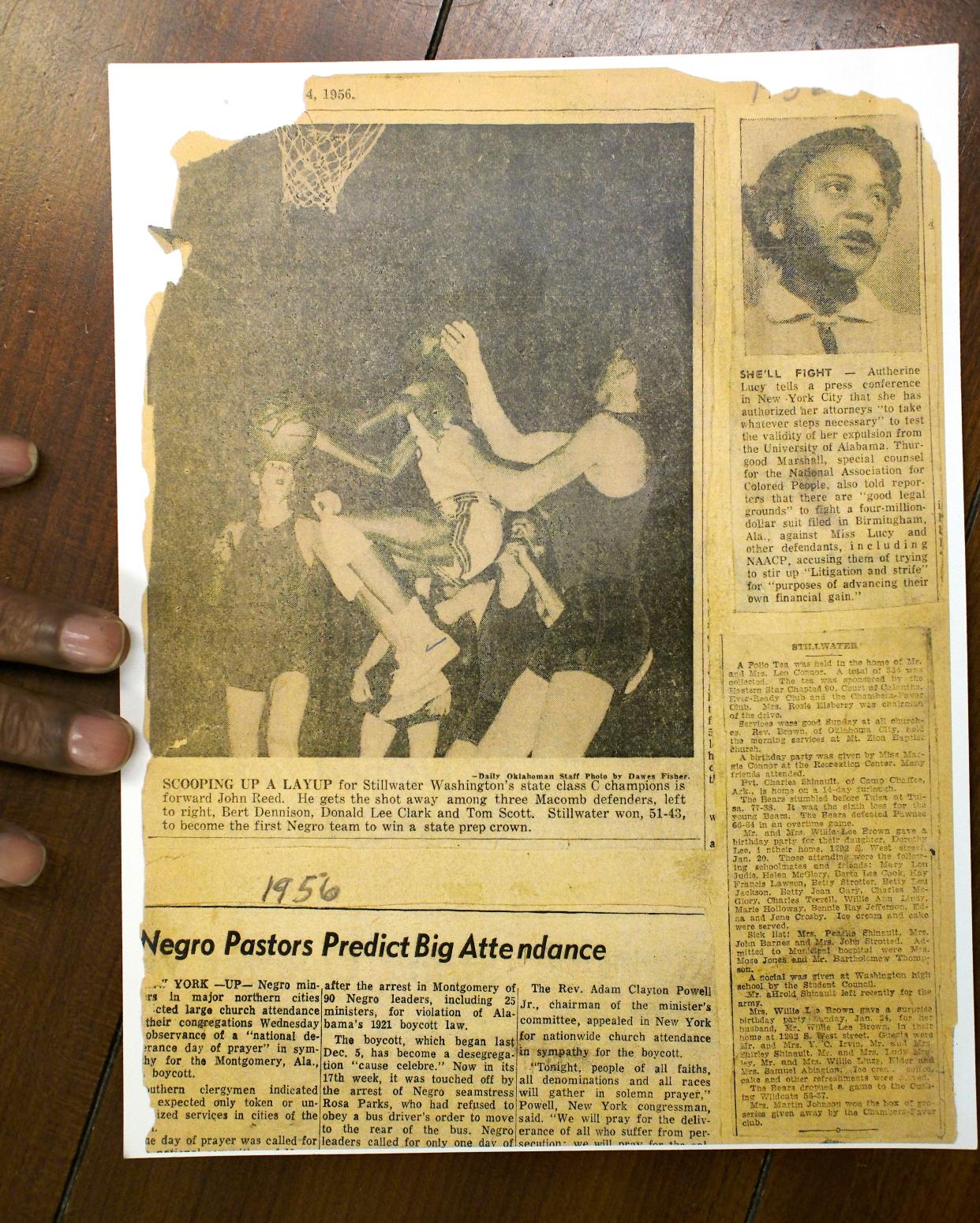

Time has frayed and yellowed the paper’s edges, but the photograph’s crisp details reveal it as a memento from only decades ago. It’s a classic, yearbook-style portrait with 10 uniformed basketball players and a coach facing the camera.

In the foreground, four trophies hint at this team’s extraordinary season.

Stillwater Booker T. Washington, Stillwater’s segregation-era Black high school, won the Class C state basketball championship in 1956, the first year of racially integrated competition at Oklahoma high school tournaments.

“This team here, it lives on,” James said. “It lives in the heart of those who remember it and know about it.”

James remembers.

The grinning sophomore wearing No. 11 in the front row of the Stillwater Daily News-Press team photograph? That’s James, the 83-year-old pastor of Central Baptist Church in Chandler.

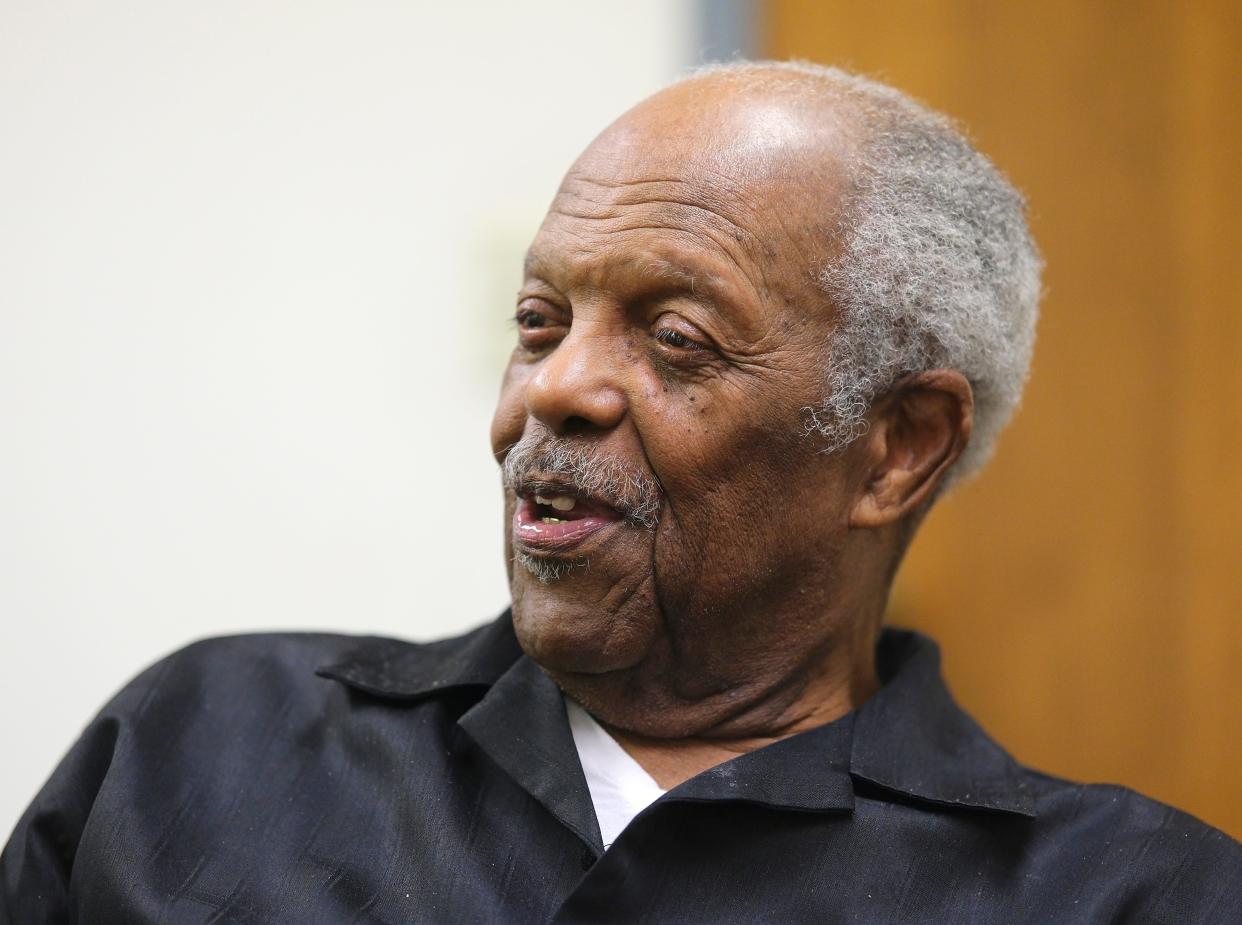

And the senior standing tall in the top row, sporting No. 55? That’s the man who sat beside James on Feb. 8 in Oklahoma City’s Fairview Baptist Church: The Rev. John A. Reed Jr., his elder brother, who averaged more than 20 points per game in his heyday.

For 68 years, John’s newspaper cutouts have survived as some of the only lasting reminders of the Washington Bears’ groundbreaking achievement.

The location of the championship trophy is uncertain. The celebration in 1956 was brief, as Washington students had a larger matter on their minds: They were integrating into Stillwater High School the following school year, leaving a building that would eventually stand dilapidated until the city’s ongoing renovation project.

Stories are lost with the lives of departed alumni, but four living team members have firsthand accounts of the Bears' championship run.

Stillwater activists are working to make sure the public knows the Bears' legacy.

Washington School Alumni Association President Karen Washington has organized a Feb. 24 banquet at Stillwater Community Center. John Reed Jr., James Reed Sr., John Cook and Charles McGlory are set to receive championship rings to commemorate their long-overlooked milestone.

Most Oklahomans haven’t grown up learning about the Washington Bears alongside sports legends like Mickey Mantle and Jim Thorpe. This small high school team isn’t typically mentioned in Oklahoma’s civil rights history, either. But the Bears’ story offers rich lessons about sports and history, reflecting the turbulent era of the 1950s Civil Rights Movement while showing how 10 Stillwater teenagers used basketball as an avenue to bravely respond to it.

Despite racist taunts and challenges no other contender faced, the sole Black school in the Class C state tournament won.

“This was the first, and look at all of the students and all that have benefitted from this since then,” said John Reed Jr., Fairview Baptist’s 85-year-old pastor. “This opened the door.”

That door was heavy and cumbersome, but the Bears pushed through as a unit.

‘Bears don’t lose’

Stillwater Washington typically played a demanding schedule.

The Bears faced tough teams in Cushing, Bartlesville and Ponca City. They wouldn’t back down from matchups with Oklahoma City Douglass, a much larger school.

When the 1956 postseason arrived, Washington had weathered these challenges to emerge as a playoff-ready program. The Bears, however, had to prepare for many opponents they had never seen.

Throughout the regular season, Washington competed in a segregated conference, facing only fellow Black schools. Then the postseason arrived, and the organization that would become the Oklahoma Secondary School Activities Association permitted integrated competition for the first time. More than 70 Black schools participated in these playoffs, and other teams’ lineups included Black players, according to The Oklahoman’s archives.

Many all-white schools were also in the bracket. This meant the Bears had to strategize against several unfamiliar opponents, but that was the least of their concerns.

More: From teachers to politicians, here are 6 influential Black Oklahomans to learn about this month

“We were excited about it,” John Reed Jr. said. “But at the same time, we were sort of reluctant.”

The players had an idea of the discrimination they would face. In 1956, America’s ground of segregation-era policies was beginning to fracture, but deep-seated racist viewpoints often weren’t changing with the laws.

For context: The Bears won state two years after the Supreme Court’s unanimous Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which declared race-based separation in public schools unconstitutional.

The Bears won state two years before teacher and activist Clara Luper led sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters at Oklahoma City’s Katz Drug Store.

Many areas of Oklahoma remained deeply segregated, and Washington started the postseason at the district tournament in rural Yale, then an all-white town.

Racism reared its ugly head in numerous ways.

Segregationist policies prevented the Bears from using Yale’s locker rooms. They weren’t allowed to shower, so the teenagers had to sit in sweaty uniforms on the 20-mile bus ride back to Stillwater.

Opposing players hurled racist slurs. Fans yelled racist slurs. Some brought black cats to the gym to taunt Washington.

“It was like being thrown to the wolves,” James said. “You couldn’t see you winning it.”

While the young athletes reasonably had their apprehensions, their mentors surrounded them with belief. If head coach Thomas Wadkins doubted the Bears’ chances, he never showed it. Alumni remember Wadkins as a man of many roles: coach, father, teacher, leader.

He held the team together.

“He cared about the players,” said Edmond resident John Cook, a sophomore in 1956. “And he cared about you not only as a player, but as an individual. He was a disciplinarian, but he allowed you to grow. He wanted you to always do your best.”

Wadkins instilled faith in the Bears, and their fan club of alumni strengthened it.

“Bears don’t lose,” the graduates would remind the players.

In the playoffs, Washington established that phrase as an indisputable fact. The Bears pulled off improbable upsets, including a defeat of a Crescent squad featuring Hubert “Geese” Ausbie, an eventual Harlem Globetrotter.

As the number of Black teams dwindled, Washington kept going.

Sixty-eight years later, a house of worship was a fitting place for the Reed brothers to reminisce on their winding championship path. The overwhelming emotions from one basketball season — frustration, pain, joy and determination — flowed through their stories with the profound power of a Sunday sermon.

James recounted a particularly moving moment from one playoff game.

When the Bears trailed at halftime, their supportive alumni provided a pep talk.

Wadkins, however, didn’t need to say a word. He walked over to the team and sat silently, James recalled, and everyone knew what to do.

“That was so encouraging,” James said. “Now, I’m 83, and I can remember everything they’ve done. I remember the feeling, and I remember how we were all looking.

“That helped to build our character, not just for that one night but for the rest of our lives.”

His older brother, who maintains the courageous spirit that has led him through a lifetime of activism, agreed.

‘All of this prepared me’

The Rev. John Reed Jr. led sit-ins as a college student, taking inspiration from Luper to integrate Stillwater’s restaurants. He met Martin Luther King Jr. soon before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

And in 1969, John participated in a strike to advocate for better wages for Oklahoma City’s predominantly Black sanitation department. Police sent him to jail, but he knew he was standing up for freedoms.

How did he have the resolve to stand in front of a sanitation truck with his fellow activists and refuse to move, even while it drove as close to them as possible?

John pointed to the photograph of 10 young basketball players and their coach.

“What happened through all of this prepared me for (activism),” John said. “I was willing to give my life for freedom. I was willing to give my life for equality for our people, and I stood there and didn’t move.”

John doesn’t know how many points he or Charles Adkins, who made The Oklahoman’s All-State team, scored in the state finals against Macomb. He and his teammates don’t recall the names of every opponent they defeated. That was hardly the point.

The alumni remember their elation after winning the state tournament. They also remember returning to Stillwater to find a harrowing symbol of hate: a burning cross outside the church where the Reed brothers’ father served as pastor. That Sunday morning, the minister led everyone in prayer.

More than six decades later, John Reed Jr. continues to see tremendous progress and hostile racism existing side-by-side in America.

“We’ve come a long ways, but we still have a ways to go as far as our civil rights and all of that is concerned,” John said. “But I’m still a part of it.

"I’m still in the struggle. I am not tired yet.”

At the once-abandoned building where he attended high school, change is ongoing. Thanks to an anonymous donor, the city of Stillwater gained the funds to repurchase the Washington High School building and begin restoring it into a public space. Set to start at 6 p.m., the Feb. 24 banquet will raise money for the Washington Heritage Project, contributing to the renovation.

The brick structure stands as a symbol of Stillwater’s past, a reminder of the triumphs of the town’s Black community despite the scars of segregation.

The championship rings will commemorate one of those great triumphs.

They’re a tangible reminder of the lessons that have guided the team members and bonded them forever.

As he reflected on those memories, James Reed's eyes kept drifting back to the group photograph in the newspaper clipping. Talking about that monumental basketball season nearly brought him to tears.

“Everything about this walks with me every day,” James said. “... This team was together.”

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: After 68 years, Stillwater Washington’s state championship 'lives on'