From stars to CEOs: The Hollywood power players launching businesses to tell women’s stories and upend Hollywood

Connie Britton doesn’t often hear the word “no.”

The Emmy-nominated actress and producer has a string of iconic credits, including starring roles in The White Lotus, Friday Night Lights, and Nashville. Well-connected in Hollywood and beyond (Barack Obama once declared himself a Britton fan), she is a venture investor, a Dartmouth board member, and a United Nations Goodwill Ambassador.

But as Britton explained to an audience of female corporate leaders at the Fortune Most Powerful Women Summit in October, the show that her company, Deep Blue Productions, was developing in 2022 wasn’t winning over the top brass at a Hollywood studio she pitched.

An intergenerational drama called Hysterical Women, it would center on four women from the same family, each experiencing a different hormonal shift. “We’ve got a daughter who is getting her period, a mother who is perimenopausal, her sister who is trying to go through fertility treatments, and then we’ve got the grandmother who is through menopause and having the best sex of her life,” Britton told the audience of women. “It’s a fantastic show! Who wouldn’t watch that show?” The audience laughed and murmured assent.

And yet, Britton told them, Hysterical Women was not green-lit. The reason for this? The studio already had a show “on the air with four women,” and executives felt there wasn’t the space—or audience appetite—for a second.

The anecdote elicited more laughter from the audience, as well as guffaws of disbelief. Granted, a show about “hysterical,” hormonal women might not be for everyone. But Britton’s point was clear: Men still run much of Hollywood.

“My company is constantly trying to expand the thinking and the understanding that women are not the only ones who are going to watch shows that feature women,” Britton told Fortune in a follow-up interview. But, she said, “there is not as much space for women-run and women-led programming.”

It’s a demoralizing observation, six years after the #MeToo movement went viral and Time’s Up, a workplace equity and anti-sexual-harassment movement spearheaded by Hollywood women, was launched. 2023 was touted as “the Year of the Girl” in pop culture, with Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, SZA, and Barbie dominating the cultural zeitgeist and adding billions of dollars to the economy in the process—but the top layer of Hollywood power is still, largely, a boys’ club.

Women will control a full three-quarters of all discretionary spending by 2028, and they make up 44% of TV viewers across platforms—but there remains a glaring disconnect between the cultural and economic impact of women as consumers, and the way that art and entertainment made by and for them is valued by industry decision-makers. Even Barbie, a wry, stylish take on women’s empowerment that has earned almost $1.5 billion to become Warner Bros.’ highest-grossing worldwide release of all time, offered a vivid illustration of this, when the movie’s director and star, Greta Gerwig and Margot Robbie, respectively, were snubbed in January’s Oscar nominations.

“The Barbie omission feels like part of a pattern in which women are seen but not heard,” says Maureen Ryan, author of the 2023 book Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood. They “are supposed to succeed and then quietly be put back into their boxes and placed back on the shelf.”

It’s not the first time that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (whose voting members skew male, with only a third female) has been accused of blind spots. In 2015, no people of color were nominated in the awards’ acting categories, prompting the viral #OscarsSoWhite campaign. Two years later, revelations of predatory behavior by the movie mogul Harvey Weinstein sent shock waves through the entertainment industry and beyond, emboldening women to speak out about the mistreatment they had endured. Then came Time’s Up, an advocacy organization started in Hollywood but focused on workplace equity and stamping out harassment across industries.

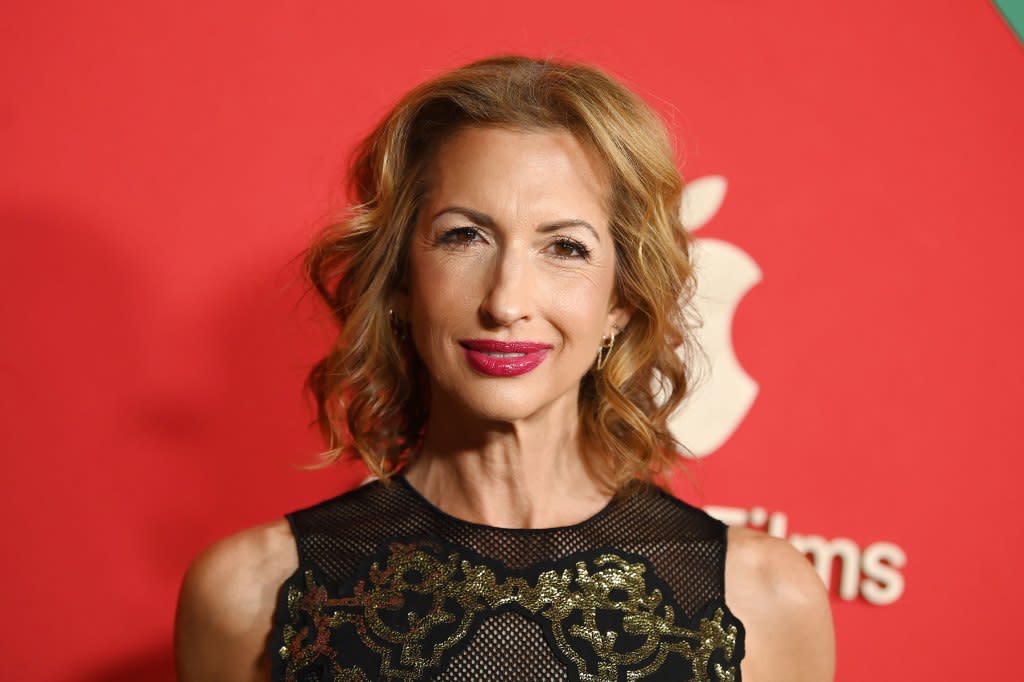

“For a multitude of reasons, during that period I felt more empowered,” says Alysia Reiner, an actress and producer known for playing Natalie “Fig” Figueroa in Orange Is the New Black. “If I see something, I say something in a different way than I did in the past. I am not the naive 22-year-old who was willing to do some really inappropriate things in the beginning of my career just because I thought that’s what you had to do.”

Since then, Time’s Up as an organization imploded amid a string of alleged conflicts of interest. #MeToo, meanwhile, has not prompted the deep societal change it once seemed poised to. But the women galvanized by those movements haven’t gone anywhere: Just as in Barbie, women in Hollywood are taking control of their own narrative.

“[With Time’s Up], there was a united power base of allies and very high-powered executives and actors who continue to run with the baton,” says Madeline Di Nonno, president and CEO of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media. “The people who were involved haven’t lost their passion or activism.”

Following the lead of women across the business world, some of Hollywood’s biggest stars—including many of an age that would once have been considered “over the hill” in Hollywood—are creating their own levers of influence to upend traditional power structures and increase representation.

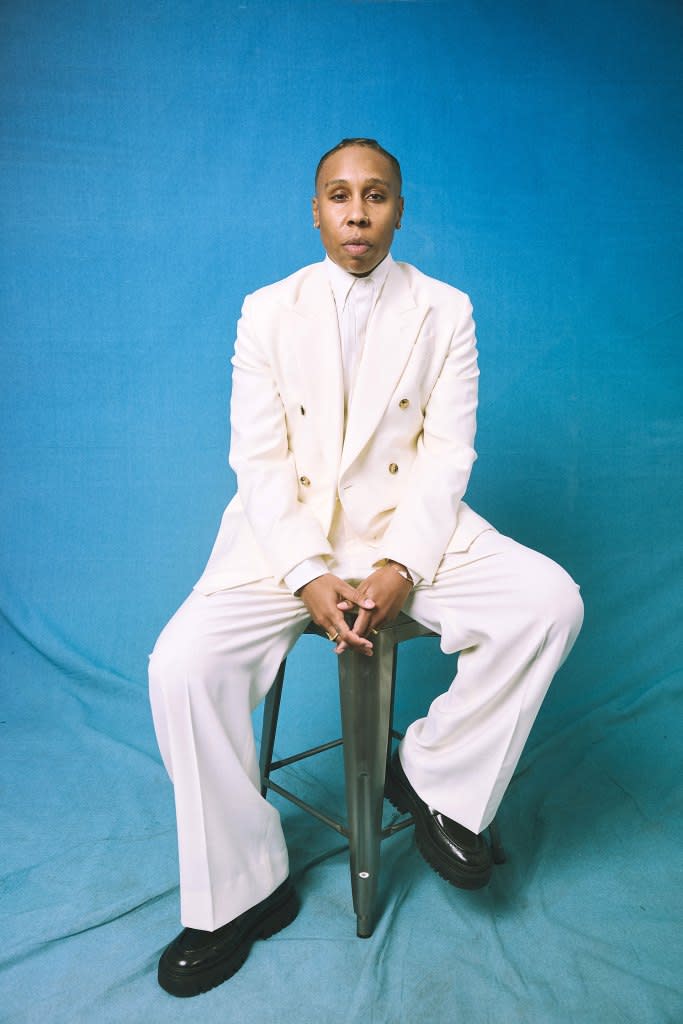

That activism looks different, as many things do, in Hollywood. Screen luminaries such as Britton, Lena Waithe, Reese Witherspoon, and Viola Davis are creating new tools for change, including female-led production companies, mentorship programs, and multi-platform business empires built on gargantuan social media followings.

Arguably, their efforts are working. At first glance, we’re in a golden age of on-screen representation for women of all ages and races: Last year, Michelle Yeoh became the first Asian woman to win the best actress Oscar—at the age of 60. The latest season of True Detective—a show that has generally featured male protagonists—stars Jodie Foster and Kali Reis, and has a Mexican woman director in Issa López. Shows with ensemble casts of women of various ages are far more common than they were in the days of The Golden Girls and even Sex and the City: Among the recent crop are Expats, Bad Sisters, Feud, and Yellowjackets. Back in 2015, the comedian and writer Amy Schumer’s sketch about the sidelining of older actresses after their “last fuckable day” went viral—but this year she’s helming the second season of her Hulu rom-com, Life & Beth. And the pipeline looks promising: Amazon recently snapped up an as-yet-unnamed miniseries starring the 49-year-old Hannah Waddingham and 53-year-old Octavia Spencer as action heroines—following a six-way bidding war.

To be sure, beyond the marquee names, the overall numbers are still rather grim. A recently published study by the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that only 30 of 2023’s 100 top-grossing movies featured women and girls in lead or co-lead roles. Depressingly, this figure is the same as that from 2010. It also represents a marked drop from 2022, when 44 of the year’s most popular films had female leads. Progress behind the scenes is equally uncertain. A different study published by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative earlier this year showed that only 12.1% of directors attached to 2023’s top-grossing films were women—only a minor improvement from 2018, when 4.5% of directors were women. While there is no concrete data about diversity at the executive level for studios, anecdotally, the situation appears to be no better. Last year, four high-ranking Hollywood diversity, equity, and inclusion executives—all women—left their roles within a 10-day period, sparking worry that a traditionally homogeneous sector of the industry was moving backward.

“There are several people who are doing phenomenally well, whether it’s Issa Rae or Ava DuVernay or Chloé Zhao or Reese Witherspoon,” says Stacy Smith, a University of Southern California professor and the founder of the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative. “The problem is that if you can think of a few examples off the top of your head and you call those to mind, you’re going to overestimate the class of events that you’re trying to figure out.”

Still, it’s worth examining the strategies that A-listers are leveraging to democratize the industry for women less recognizable than themselves. Many of them are fusing their activist principles with shrewd business strategy. Here are four of those approaches.

Becoming online tastemakers

In 2013, the actress and producer Reese Witherspoon created an Instagram account. She posted a Mother’s Day message before uploading a photo of J. Courtney Sullivan’s novel The Engagements. ”I love this book!” she wrote in the caption. “Has anyone else read?”

This unassuming window into Witherspoon’s off-screen life was the genesis of Reese’s Book Club, an online reading community with almost 3 million Instagram followers that became a media powerhouse. It’s a model that Oprah’s Book Club, which has made stars (and multimillionaires) of various authors, pioneered. And there’s a reason it seems like every actress has her own book club these days: Such clubs can build attention and fan bases for books, helping movie and TV show adaptations get green-lit.

Four years after her first Instagram book post, Witherspoon officially launched Reese’s Book Club in partnership with her production company, Hello Sunshine, announcing that she would spotlight one woman-centered book per month. The launch came the same year that the company’s adaptation of Big Little Lies won eight Emmys, proving that if anyone could spot a story that would captivate audiences and critics alike, it was Witherspoon.

The book club swiftly became a literary kingmaker (or queenmaker, usually). Less than 12 months after Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens was selected by Witherspoon in 2018, the novel had sold over a million copies, an impressive feat for a work by a then unknown author whose initial print run was about 28,000. The book has since been adapted—by Hello Sunshine, of course—into a movie that made $144.3 million at the global box office on a reported $24 million budget. Its commercial success attests to the power of Witherspoon’s multi-platform strategy.

Witherspoon’s chatty tone and frequent, carefully controlled glimpses of her homes, her children, and her starry friendships made her a megawatt lifestyle influencer, while her 30 million followers made her Instagram account a powerhouse when it comes to popularizing the books, films, TV shows, and fellow artists that she champions.

Sarah Harden, CEO of Hello Sunshine, says Witherspoon takes engagement with her fan base seriously, poring over her own social media analytics. “Reese is hearing from and interacting with women,” she says. And it’s working on many levels: Witherspoon has hit upon a startlingly effective formula for boosting the value of the all-important “intellectual property” that Hollywood relies upon.

The actress, writer, and producer Lena Waithe is doing something similar: Her media company, Hillman Grad, has a book imprint in partnership with the independent publisher, Zando. “Every book doesn’t need to be turned into a movie or a TV series, although it’s a pipeline that we’re seeing, and it kind of makes sense,” Waithe tells Fortune. “If a book does well, it already has a built-in audience.”

Holding the door open

Mentorship has always existed in Hollywood, and has been particularly important for women: Jane Fonda learned from Katharine Hepburn on the set of On Golden Pond, while Meryl Streep frequently dispenses life advice to Viola Davis. But the glaring inequalities exposed by the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements have inspired some to develop more formal, business-focused strategies in order to increase the number of women and people of color rising to leadership roles. Ava DuVernay, for example, famously uses her influence to promote the work of up-and-coming, mostly Black filmmakers.

Hello Sunshine is focusing on entrepreneurial mentorship with the recently launched Hello Sunshine Collective, which provides female business leaders and content creators with support from the company’s leadership in areas including marketing, strategy, and partnerships. The collective worked with 17 women for its inaugural cohort. Similarly, Waithe’s Hillman Grad incorporates a Mentorship Lab for creatives from underrepresented backgrounds. Mentees accepted to the eight-month, tuition-free program are separated into three tracks: writing, acting, and executive development.

That last category is particularly important, Waithe points out: “Most execs and people who have green-lighting ability don’t look like me,” she says. “And if there is somebody in that office or C-suite who does look like us, there’s usually only one of them, so they can probably get maybe one or two movies through.”

Aline Brosh McKenna, a writer, producer, and director whose credits include The Devil Wears Prada and 27 Dresses, recalls becoming a protector figure for the writer and actress Rachel Bloom when they cocreated the CW show Crazy Ex-Girlfriend in 2015. Bloom was in her twenties at the time, while McKenna was two decades older. “It really ignited a maternal instinct in me,” McKenna says. “I had the strong instinct to protect her creative vision.”

Since then, McKenna has helped others achieve long-lasting careers as writers and directors via her production company, Lean Machine: “We try to have our office be like a little de facto writers’ room where we’re always there to help, and people can come by and get snacks and put their feet up. It’s a lonely business being a writer, and so we try to create a sense of home.”

In the post–Time’s Up era, much of Hollywood women’s activism occurs via quiet, unofficial circles of power that are founded on personal relationships. “People say in our industry it’s about relationships,” says Waithe. “I think you could change that. It’s actually about friendships, because you can have a relationship with a lot of people, but if you have a real friendship, it becomes about more than the business.”

Mixing friendship with business has become an important power move in the fight for gender equality in Hollywood—whether it’s Jamie Lee Curtis and Jodie Foster publicly proclaiming their “besties” status, or Witherspoon championing projects that provide her friends (Laura Dern, Nicole Kidman, and Jennifer Garner, to name a few) with interesting roles in middle age. Scroll through social media and you’ll see America Ferrera and Eva Longoria or Salma Hayek, Zoe Saldana, and Penélope Cruz declaring their love and admiration for one another.

While these posts aren’t explicitly activist, their proliferation sends a potent message to networks and studios: The industry’s most influential women are now a united front, prepared to share ideas, pay-equity data, and experiences in the name of making Hollywood more democratic.

Speaking out about fair pay

In 2018, it emerged that the actress Michelle Williams was paid significantly less than her costar, Mark Wahlberg, to appear in All the Money in the World, a film about the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III. The following year, when accepting the best actress Emmy for a different project, Williams made an impassioned plea to employers: “Next time a woman—and especially a woman of color, because she stands to make 52 cents on the dollar compared to her white, male counterpart—tells you what she needs in order to do her job, listen to her,” Williams said. “Believe her.”

Since then, women in the industry have only become more vocal on the subject of gender- and race-based pay discrepancies. In recent months, for example, The Color Purple’s Taraji P. Henson has candidly discussed the racial pay gap that she has experienced throughout her career. And it was because of the racial pay gap that Jessica Chastain used the “favored nations strategy”—a contractual term meaning that all parties make equal deals—when she and Octavia Spencer negotiated their salaries for a film they were to costar in. Meanwhile, The Crown’s Claire Foy has reflected on her discovery that her costar, Matt Smith, was paid more than her despite the fact that she was the show’s star for the two seasons they appeared in together—and said she’s grateful that such pay discrepancies negotiated behind closed doors are now harder to keep secret.

“There’s been a lot more outspoken activism,” says Liz Alper, a TV writer and producer and the cofounder of PayUpHollywood, an advocacy organization for entertainment industry support staffers and assistants. The need for fair pay for all workers in TV and film is “talked about much more openly than it used to be, which is wonderful,” she says, adding, “We still have a long way to go.”

As in the corporate world, however, admitting to being underpaid can come at a reputational cost. “You want everyone to perceive you as making a lot of money,” says Reiner. “It’s extremely vulnerable to ask, ‘How does it affect my business and my worth if I acknowledge to others that I am not making as much as they perceive me to be making?’” Last year, Reiner told The New Yorker that she didn’t feel she was paid in a “commensurate” way for Orange, a Netflix series launched in 2013 that was set in a women’s prison and featured a mostly female ensemble cast.

Whatever their gender, Waithe cautions writers and directors starting out in the industry to think long-term about their earning potential. “It’s not just about, ‘How can I get the biggest check?’” she says, pointing out that once a new talent has “proven” their ability to make money for a studio or streamer, they can negotiate more aggressively. “We kind of come in and go, ‘Hey, I want to get paid.’ We all do. But you’ve got to prove that there’s proof in the pudding.”

Taking power behind the scenes

While actresses running production companies is not a new concept (Mary Pickford, Lucille Ball, and Mary Tyler Moore all launched their own companies—albeit alongside their husbands—in the 20th century), today the evolution from actress to business leader is a rite of passage for women wanting to future-proof their careers while also influencing the direction of the industry. (Many of Hollywood’s leading men have taken the same route, of course.)

“I think that it’s been wonderful for very powerful artists to say, ‘I’m going to be in control of my destiny, and I’m going to kick the door open,’” says Di Nonno. “‘Not only are these [projects] potentially vehicles for myself, but I’m going to open the door and pull everybody up with me.’”

Britton, as well as Natalie Portman, Margot Robbie, Oprah Winfrey, Kerry Washington, Jennifer Aniston, and many other A-listers have production companies. But it is Witherspoon’s Hello Sunshine that provides the most visible example of an actress building an empire. Since its inception in 2016, the company has made 15 TV series and seven film projects, including The Morning Show, Daisy Jones & the Six, and of course Big Little Lies, which broke ground in 2017 by bringing a movie-star cast (Witherspoon, Nicole Kidman, Laura Dern, Shailene Woodley) to the small screen.

The show, an adaptation of the novel by Liane Moriarty, centered on the complicated lives of a group of privileged, middle-aged Californian women and became an awards magnet, as well as a roaring ratings hit; according to HBO, the series’ second season drew an average of 10 million viewers per episode across all platforms. Its success marked a watershed moment for TV, proving that a show about friendships between women with complex, adult lives could become a critical and commercial juggernaut. (Rewind seven years to a world before Big Little Lies, and it’s difficult to imagine executives getting so excited about a show featuring middle-aged action heroines such as Waddingham and Spencer.)

“The lack of women seeing their full lived experience on the screen was an opportunity we’ve all stepped into,” says Harden. “It’s no surprise to anyone that audiences show up if you execute, and our job is to execute really, really well … Addressing this authorship and representation gap is big business.”

That thesis is being tested in the marketplace: In 2021 Witherspoon sold a majority stake in Hello Sunshine to the Blackstone-backed Candle Media for $900 million. But last year, the company’s profit came in at only 10% of its projected $80 million, a shortfall that Candle Media attributed to the Hollywood strikes and other industry headwinds.

Harden is often asked whether Hello Sunshine prioritizes its mission of “supporting women who have unique voices and lived experiences” over profitability (a question corporations trying to balance profits with social and environmental impact are familiar with). “Everything we do has to do both,” Harden says. “We cannot do the next thing if we do not build a financially successful, profitable company. Our success is a form of power because it allows us to say yes to things or no to things without unnatural pressures.”

Still, USC’s Smith cautions against taking these examples of stars championing women-centric productions as a bellwether of the broader situation across Hollywood. “I would say it’s hope for folks to look to, but they are not representative of the hiring practices that apply to the rest of the industry,” she says, citing a 2023 Annenberg Inclusion Initiative study that shows only 25.8% of speaking characters over age 40 were women in 2022’s 100 most popular films. “If your name is not Meryl, Maggie, or Judy, your opportunities are going to be very limited.”

The on-screen representation of mothers is a particularly fraught issue. Just this week, Meghan Markle announced that she has collaborated with the Geena Davis Institute and a charity, Moms First, on a study that analyzes the portrayal of mothers in scripted TV shows. The results highlight a lack of diversity: Moms are largely depicted as white, young, thin, and rarely as the breadwinner for their families. And the actress Kirsten Dunst told Marie Claire that she was sick of being offered only “sad mom” roles.

Meanwhile, Britton is still trying to get Hysterical Women green-lit. The experience has supercharged her determination to champion stories about the less-explored facets of womanhood, she told the audience at the Fortune conference: “Pushing up against the structures that are in place to prevent us from even having those shows on the air,” she said, is now “part of the job for me.”

She’s also developing a makeover-style reality show built around overstretched single mothers with Scout Productions, the company behind Queer Eye. Britton envisages a nuanced, empathetic show that steers clear of sensationalist TV clichés, but that has proved easier said than done. The network that Britton was originally working with on the show “wanted things … that hit you over the head,” and so they parted ways.

“I think we have found a new home for it,” she tells Fortune. “Suffice to say, I will not quit until the show is on the air.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com