Stargazing in October: A sleeping giant

Look high in the south on a dark moonless night, well aware from the glare of streetlights, and you’ll find a faint glowing patch of light. It’s the only object you can easily see with the naked eye – from northern latitudes - that’s not part of our Milky Way galaxy.

That faint fuzzy patch in the constellation Andromeda is a galaxy in its own right: a giant star-city even larger than the Milky Way, lying 2.5 million light years away. The light falling into our eyeballs now left the Andromeda galaxy before human beings even existed.

The first person we know to mention the Andromeda galaxy was the Persian astronomer Al-Sufi, who in 964 described it as a “nebulous smear.” Well into the nineteenth century, many astronomers thought it was close to the Sun: maybe a disc of gas around a nearby star that was forming a system of planets.

But in 1925, the American astronomer Edwin Hubble measured the distance to Andromeda by picking out individual stars that change in brightness. He proved it was a separate star-system from the Milky Way – what many at the time called an “island universe.”

In the ensuing century, professional astronomers have dissected the Andromeda galaxy minutely, using their most powerful instruments, from immense radio telescopes and satellites that detect X-rays, to the James Webb Space Telescope.

But they overlooked one of Andromeda’s largest and strangest features, a huge curving gas cloud to one side of the galaxy that’s glowing green in the light from oxygen atoms.

This “plasma arc” was discovered last autumn by three amateur astronomers in France, using a telescope with a lens only 10.6 cm across – the size of many beginners’ telescopes. But Marcel Drechsler, Xavier Strottner and Yann Sainty equipped it with a sensitive wide-field camera, and a special filter that passes only light emitted by oxygen atoms. The three were recently named the overall winners of the Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2023 competition for an image of their discovery.

The green arc that the trio discovered is probably a long streamer of gas that’s been torn out of a small galaxy by Andromeda’s immense gravity. The real puzzle, though, is why is it glowing?

The answer probably harks back to another discovery made by an amateur astronomer. In 2007, Dutch schoolteacher Hanny van Arkel was taking part in a project called Galaxy Zoo, where members of the public were asked to classify images of almost a million galaxies photographed by a robotic telescope. She found a strange green blob lying next to the spiral galaxy IC 2497. It was so unlike any normal galaxy that astronomers call it Hanny’s Voorwerp – Dutch for “Hanny’s Object.”

Astronomers now think that Hanny’s Voorwerp is a small gas-filled galaxy that has been lit up by intense radiation coming from the core of IC 2497. Like almost all galaxies, IC 2497 harbours a supermassive black hole at its heart. About 70,000 years ago, gas swirling around the black hole shone intensely brightly as a quasar – a tiny brilliant object that’s more luminous than an entire galaxy.

The green arc near Andromeda is probably a sibling of Hanny’s Voorwerp, a gas cloud lit up by an intense outburst from the galaxy’s core. Andromeda has a central black hole as heavy as 140 million suns - some 30 times heavier than the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. At the moment, Andromeda’s centre is quiet, with no sign that the black hole is ingesting any gas.

But black holes are irregular eaters. Undoubtedly in the past, Andromeda’s supermassive black hole must have ripped up and eaten passing stars and gas clouds. The core then shone brilliantly, lighting up the green plasma arc. Though we can still detect it today, the glowing gas streamer is now gradually fading away.

So Andromeda is not just a gentle giant of a galaxy: it is a sleeping quasar, merely resting until it’s time to erupt again in a blaze of glory.

What’s Up

The Earth is treated to two eclipses this month. On 14 October, the New Moon moves between us and the Sun. The Moon is at the far point of its orbit and appears significantly smaller than the Sun’s disc. As a result, when the two orbs are lined up, we see a circle of the Sun’s brilliant surface around the Moon’s silhouette. To view this ‘circle of fire’ – technically an annular eclipse - you need to be in the western United States: the rest of the Americas will see a partial eclipse, but nothing is visible from Britain or Ireland.

We’re better off with the eclipse of the Moon on 28 August, which is visible from these islands between 8.35 and 9.53 pm. But the Moon just dips into the shadow: at mid-eclipse only 12 percent of the lunar shining disc is obscured. The brilliant object nearby is the planet Jupiter.

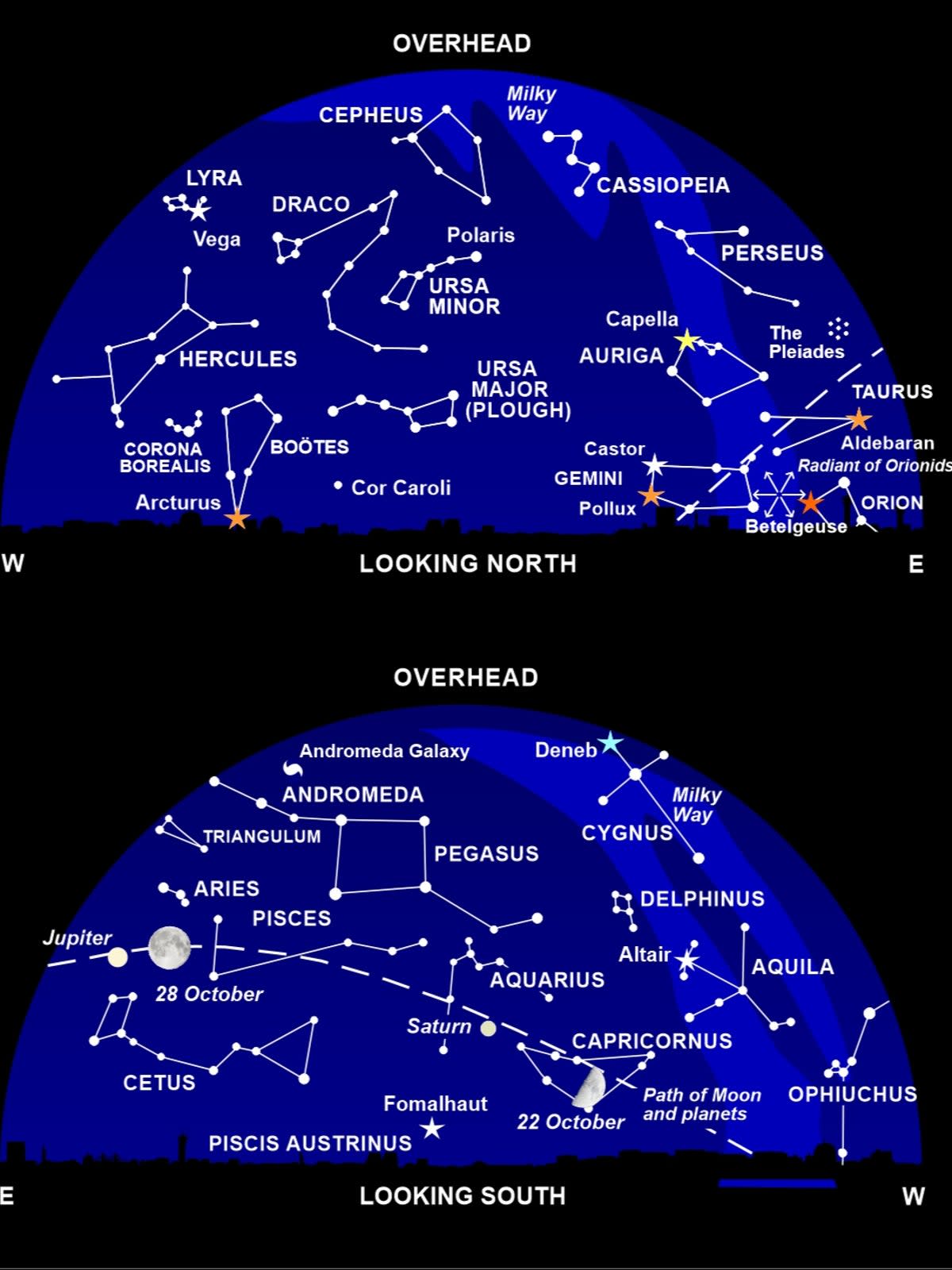

Also, look out for fragments of Halley’s Comet slamming into the atmosphere on the night of 21 October, and burning up as the Orionid meteor shower. The best views of these speedy shooting stars will come after the Moon has set around 10 pm, and the sky is really dark.

Throughout October, Jupiter is brilliant in the southeastern sky, outshining all the stars with a steady creamy-white glow. To the left of Jupiter you’ll see the Pleiades, the lovely glittering star cluster that also rejoices in the name the Seven Sisters. Lower down lies the orange giant star Aldebaran, marking the eye of Taurus (the bull), with the great hunter Orion now starting to rise above the horizon.

Over in the southwest, Saturn is prominent in a region devoid of bright stars, in the midst of the faint sprawling constellations of Aquarius, Capricornus and Piscis Austrinus. The Moon is nearby on 23 and 24 October.

If you’re up before dawn, you can’t miss Venus low in the east. The Morning Star is more brilliant than anything else in the night sky bar the Moon. The crescent Moon is nearby in the mornings of 10 and 11 October.

Diary

6 October, 2.48 pm: Last Quarter Moon near Castor and Pollux

10 October, early hours: Moon near Venus

11 October, early hours: Moon near Venus

14 October 6.55 pm: New Moon; annular solar eclipse

18 October: Moon near Antares

21 October: Maximum of Orionid meteor shower

22 October, 4.29 am: First Quarter Moon

23 October: Venus at greatest elongation west; Moon near Saturn

24 October: Moon near Saturn

28 October, 9.24 pm: Full Moon near Jupiter, partial lunar eclipse

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky next year