Stargazing in July: Sagittarius and the Milky Way

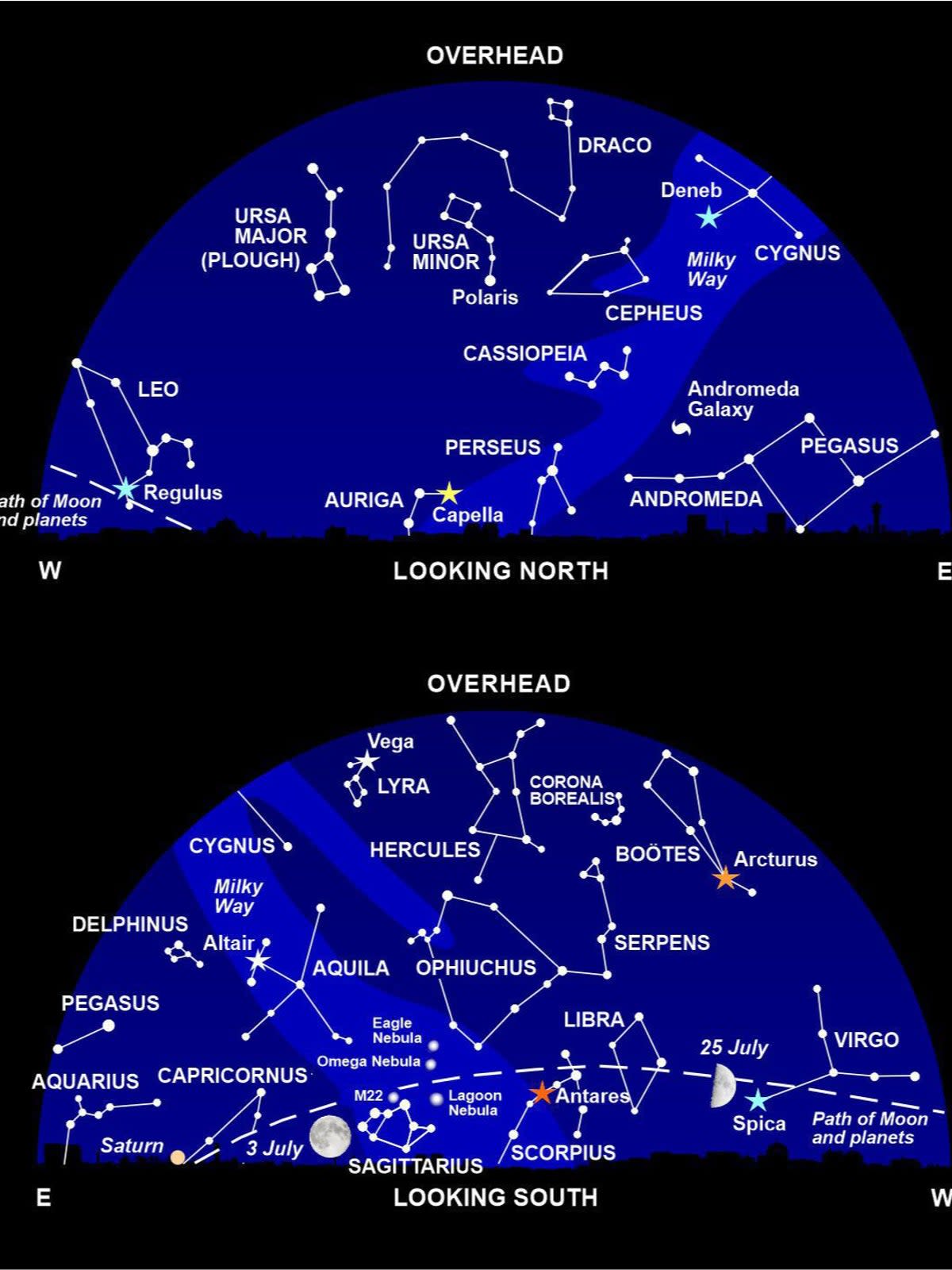

Galloping along the southern horizon this month is a celestial centaur – half-man, half-horse – gripping a bow-and-arrow directed at the heart of a treacherous scorpion. That’s how the ancient Greeks saw the stars of the constellation Sagittarius, but most astronomers today use the nickname "the Teapot" for the brightest stars: once you make out this shape (see the starchart below) you can never forget it!

The origins of Sagittarius go way back before the Greeks, though. Stone carvings from ancient Mesopotamia, dating back 3000 years, depict this constellation as a creature with the body of a horse and the torso of a man holding a bow: it also has an extra tail (of a scorpion) and a second head (of a panther), as well as pair of wings. It was associated with Pabilsag, a god of war and hunting.

The Greeks inherited only the basic man-horse shape with his weapon, and named the star-pattern Sagittarius, meaning "the archer". They didn’t have any particular myths for this constellation, as they had a similar celestial creature – the constellation Centaurus – that embodied their wise centaur, Chiron.

Most of Sagittarius’s body is composed of faint stars to the lower left of the Teapot. The handle of the Teapot represents the archer’s shoulder and the hand that’s drawing back the bowstring. The curve of three stars to the right is the bow itself; and the spout of the Teapot is the tip of the arrow, pointing towards the red star Antares, the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion).

The centre of our galaxy – with its massive black hole - lies behind the stars of Sagittarius, though dense dust clouds in space obscure our view of what’s happening there. But even with the naked eye you can see that the Milky Way appears broadest and brightest in this direction, as we look towards our galactic downtown.

The Milky Way here is rich in nebulae and star clusters. Look above the spout of the Teapot on a clear dark night, and the fuzzy patch you’ll spot is the Lagoon Nebula. Lying 5000 light years away, it’s a nest of young stars amid glowing gas. The Lagoon is a wonderful sight through binoculars, which will also show the nearby Trifid Nebula and the star cluster M21. They’re all magnificent as seen with a small telescope.

Sweep the Milky Way with your binoculars above the lid of the Teapot to track another glorious star-forming region, the Omega Nebula. Above it you’ll find a close twin, the Eagle Nebula, in the adjacent constellation of Serpens. At the centre of this gas cloud lurks a trio of dark columns of dust, famously captured in a stunning image from the Hubble Space Telescope as the Pillars of Creation.

M22 is another fuzzy patch near the Teapot’s lid, visible to the naked eye from southern latitudes, where Sagittarius rises high in the sky. With a telescope, you can see that M22 is not a glowing gas cloud, but a tightly bound swarm of stars. Astronomers estimate that the cluster – lying 10,600 light years away – contains half a million stars and was born 12 billion years ago, soon after the Big Bang that created our Universe.

What’s Up

Glorious Venus reaches its greatest brilliance early this month. The Evening Star has been a fixture in our skies since last December, but at the end of July it disappears from sight, as Venus swings between the Earth and the Sun.

At the beginning of July, Mars lies close to Venus, with the Red Planet 300 times fainter than the Evening Star. Just after sunset on 19 and 20 July, you’ll find these two planets low on the western horizon close to the crescent Moon, along with innermost planet Mercury and Leo’s brightest star, Regulus.

As these planets set, Saturn is rising in the east. And if you’re up after 1 am, you’ll see brilliant Jupiter, too. The Moon passes Jupiter before dawn on 12 July.

Four of the brightest stars are spread out over the southern sky. Almost overhead you’ll find Vega, the jewel of the little constellation Lyra (the Lyre). It’s a hot star, and pure white in colour – unlike our yellowish Sun. Well to its lower left, another white star hangs in the sky: in Arabic, Altair’s name means “the flying eagle,” and it forms part of the constellation Aquila, the Latin for “Eagle.”

Orange Arcturus, way over to the right, is a giant star that’s swollen up towards the end of its life. Its colour shows that Arcturus is cooler than the Sun, and it’s about 25 times wider than our star. Finally, low in the south lurks bright red star Antares, in Scorpius (the Scorpion). Even larger than Arcturus, with a width of 680 solar diameters, this cool red giant star will soon explode as a supernova – though “soon” on the astronomical timescale means within the next million years!

Diary

12 July (am): Moon near Jupiter

17 July 7.32 pm: New Moon

19 July: Moon near Mercury, Venus and Mars

20 July: Moon near Venus, Mars and Mercury

24 July: Moon near Spica

25 July, 11.07 pm: First Quarter Moon

28 July: Moon near Antares

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2023’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year