After stalking, peeping and indecent exposure, women say criminal system fails them

Jan. 11 seemed like just another ordinary night. A 26-year-old hanging out in her studio apartment in Grosvenor Gardens, a historic u-shaped complex surrounding a landscaped courtyard on Hillsborough Street.

The woman ate dinner in her pajamas, sat on her blue velvet couch and watched Netflix. She slipped under her pale pink comforter and fell asleep.

The next day, memories of that serene night made her stomach drop.

Neighbors spotted a man peeping into her windows as she relaxed, the apartment complex’s management told her the next day. They caught his tag number and shared it with police.

That launched the first wave of anxiety and anger. The next washed over her after a Google search showed the man police identified, Petree Leray Anderson, 44, had a history of stalking and indecent exposure charges in incidents covered by local news outlets.

“Why is this guy out?” said the woman, who asked not to be identified over concerns for her safety. “That was my first thought.”

Three women who police say Anderson has targeted are frustrated that the courts and others haven’t stopped what appears to be Anderson’s pattern of violating women.

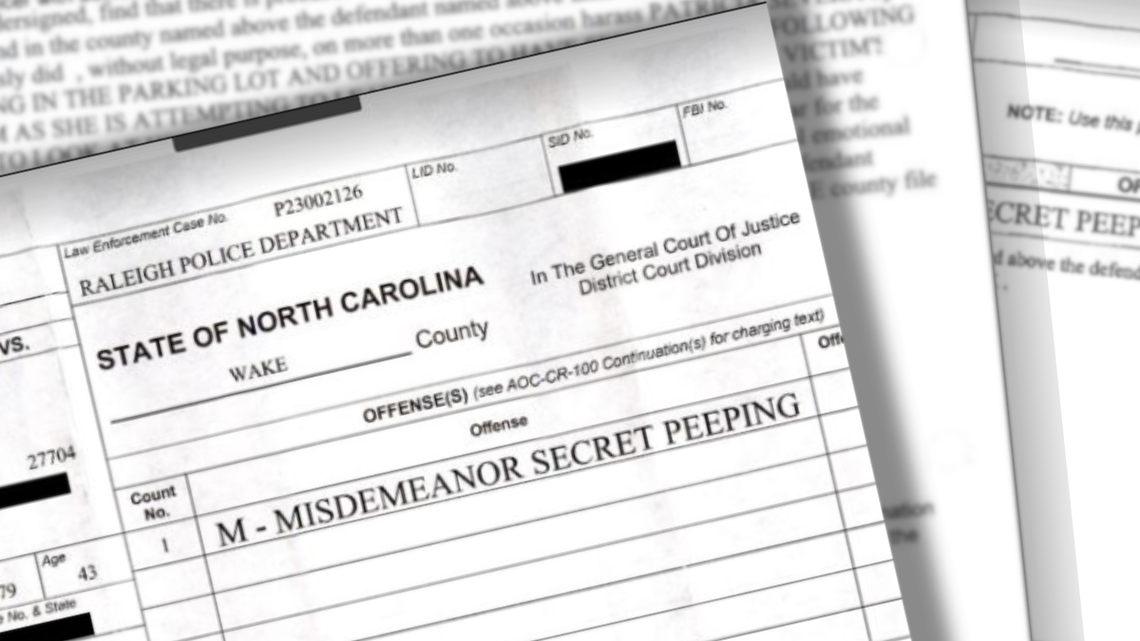

Charged with secret peeping for Grosvenor Gardens incident, Anderson’s pattern includes stalking, soliciting sex from women he does not know and fondling or exposing himself in front of strangers, court and police records say.

These aggressions are deemed misdemeanors by state law and not as serious as a physical assault. But they change lives, the women say, and left them on high alert, prompting them to make unplanned moves and in some cases, buying guns.

Anderson’s public defender, Lucy Campbell, declined to be interviewed for this story.

History of charges

Since 2016, Anderson has been charged with secret peeping, indecent exposure and stalking, in eight incidents involving nine women in Wake County. The women happened to cross his path at a park, a library and on a morning walk, according to court documents and interviews.

In four of the incidents, Anderson pleaded guilty to all or some of the accused crimes, including one plea that combined two cases. His maximum sentence was 150 days, the longest he could spend incarcerated for a single misdemeanor crime.

Anderson currently has three pending charges from incidents in 2021, 2022 and 2023.

The News & Observer spoke with four women Anderson has been criminally accused of harassing. Each say something must be done to stop him from stalking and harassing women. But they differ on the best steps.

“I am not sure what the world should do with Mr. Anderson,” said a woman who Anderson approached in September 2016 on a morning walk in Raleigh. Anderson then showed up near the woman’s home and approached her 20 minutes later, she said.

It seems like he needs mental health help, not incarceration, she said.

She did advocate for Anderson to get mental health treatment when her case reached court, she said. A June 23, 2017, letter in the case file indicated that Anderson had a comprehensive clinical assessment.

In a 2019 case, Anderson’s sentence also included a complete mental health evaluation and an order that he comply with treatment, according to court documents.

Other women who have accused Anderson of stalking and other crimes more recently said they think he should be put behind bars for a significant time. One blames court officials for not holding Anderson accountable.

You can’t change a behavior if there are no consequences, said a woman who Anderson followed into a Wake County homeless facility and then exposed himself, court records say.

“Why hasn’t this been resolved? What are they really waiting for before they are going to take action?” she asked.

Coordination of care

Sometimes people who repeatedly commit crimes such as peeping and indecent exposure are just criminals, said psychiatrist Dr. Jacqueline Smith, speaking generally rather than about Anderson specifically.

“But sometimes there is more to it,” said Smith, who supervises behavior health services provider Monarch’s outpatient clinics across the state, including Wake County.

Sometimes individuals are dealing with voyeuristic or exhibitionist disorders, causing “persistent, uncontrollable urges to engage in these behaviors,” even when it causes them personal and legal issues, she said.

“It’s a balance of holding folks accountable, but not infringing too much on the perpetrator,” Smith said.

Such urges are typically treated with therapy and possibly medication, Smith said.

They will reoffend if there is not meaningful intervention,” she said.

Ideally, someone whose sentence includes court-ordered treatment would seek a knowledgeable provider who could provide effective treatment, which would extend over six months to a year.

However, it doesn’t typically work out that way, Smith said.

Sometimes offenders go to providers who may not be familiar with their specific issues, and their treatment is limited to their short sentences, she said. Other times they don’t finish the treatment plan, or they do complete it but don’t engage and follow the recommendations.

A factor that could contribute to someone committing serial crimes, she said, is poor coordination of care between the justice system and mental health providers, Smith said.

There is not a consistent avenue for mental health providers to alert courts about the patient not following the treatment, Smith said.

3 current charges

In the 2021-22 fiscal year, there were 1,122 misdemeanor stalking charges filed in district courts across the state, according to state court data. There were also 570 indecent exposure and 67 secret peeping charges filed.

In Wake County, those three crimes were charged a total of 159 times during that period.

Currently in Wake, Anderson is accused of secretly peeping at Grosvenor Gardens in January and urinating in public after being charged with trespassing at a Wake ABC store in December, according to court documents. In the third case, Anderson is charged with felony stalking.

In North Carolina, individuals can face a felony stalking charge after they are convicted of misdemeanor stalking. Anderson was convicted of two counts of misdemeanor stalking in 2018 and one count in 2019.

Anderson’s first felony stalking case is pending after he was accused in 2021 of repeatedly harassing a woman at a Raleigh recreational facility, following her around and offering to have sex with her, according to court documents.

When the woman Anderson is accused of harassing at the park facility in 2021 learned he would be charged with a felony, she said she felt it was her responsibility to move the case forward. The Class F felony has a maximum punishment of 59 months.

“If I don’t press charges and he gets out, then I would feel like I am responsible,” she said.

Beyond stalking, the other charges Anderson has been accused of include secretly peeping and indecent exposure, which are both misdemeanors.

If someone is convicted of secret peeping a second time, a judge could rule the person a danger to the community and require them to register as a sex offender. Anderson is not listed as a sex offender on North Carolina’s registry.

A shift in security

Impacts on stalking victims include fearing what could happen next, missing work, and moving, along with suffering higher rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia and other issues, according to the Stalking, Prevention, Awareness & Resource Center.

The 26-year-old who Anderson is accused of peeping on in January said she went from feeling like a confident and independent woman to being fearful and untrusting.

“The second it happens, you view every single person you pass by in the street differently,” she said.

The Wake County district court system handles about 100,000 criminal cases alone. Unlike with many misdemeanor cases, assistant district attorneys are assigned to cases that fit under the category of a type of sexual battery, including stalking, peeping and similar cases, Freeman said.

“It is one where we tried to have real contact with the victim, but like with everything given the intense volume that we have down there, and the limited resources, it can be a challenge to be responsive to victims as they would like and hope,” said Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman.

But in at least three of the cases in which Anderson was charged, there have been glitches or concerns about communication between criminal justice officials and his accusers, according to the women.

The miscommunication could be the result of a number of hindrances, including incomplete paperwork, a change of district attorney staff, victims failing to register with the state, and the heavy workload for assistant district attorneys and public defenders, according to interviews and court documents.

In the 2023 case originating at Grosvenor Gardens, Anderson’s alleged target wasn’t contacted before his court hearings, she said. That included a hearing in which his bond went from $1,000 secured to $5,000 unsecured, which means Anderson didn’t need to put any money down to be set free. The conditions of his release included participating in pretrial release program and not contacting the victim or witness.

Since the woman wasn’t notified, she wasn’t able to attend the hearing and argue for a higher bond.

Notifying the victim is triggered by a form filed by police, Freeman said, which staff in the District Attorney’s Office couldn’t locate.

The Raleigh Police Department didn’t directly respond to questions about the paperwork. Spokesman Jason Borneo wrote in an email that the department is committed to ensuring victims and witnesses are treated fairly and provided with information about their case.

The woman accusing Anderson in the 2021 felony stalking case said the process has been frustrating for her as well. “It has been postponed, postponed, postponed,” she said.

A woman involved in a 2019 case in which Anderson took a plea deal, causing the charges in her case to be dismissed, said she was never notified about court dates or the resolution.

Virginia Bridges covers criminal justice in the Triangle and across North Carolina for The News & Observer. Her work is produced with financial support from the nonprofit The Just Trust. The N&O maintains full editorial control of its journalism.