Yes, the NFL puts microchips in footballs, but they’re not ready for prime time on key calls – yet

Late in the fourth quarter of a prime-time showdown, with the NFL’s last undefeated record in peril, Aaron Jones slammed into a wall of Arizona Cardinal defenders and disappeared.

Referees ran toward him. One signaled touchdown. Back in a New York office, and up in a stadium booth in Arizona, NFL officials questioned the call on the field. They scoured video for evidence. They watched one replay, then a second. Then a third, a fourth and a fifth. They needed proof that Jones’ backside had touched down before the ball reached the goal line. What they soon realized was that, with 300-pound men surrounding Jones, a single confirmatory camera angle did not exist.

What they also might have realized was that, beneath the surface of NFL games, technology that could’ve assisted them does exist.

For decades, the NFL has relied on stripe-shirted humans with imperfect judgement and obstructed views to spot footballs; to determine whether runners reach yard lines or goal lines; to pinpoint where balls cross sidelines. In real-time, it’s often impossible. Even on replay, it can be difficult.

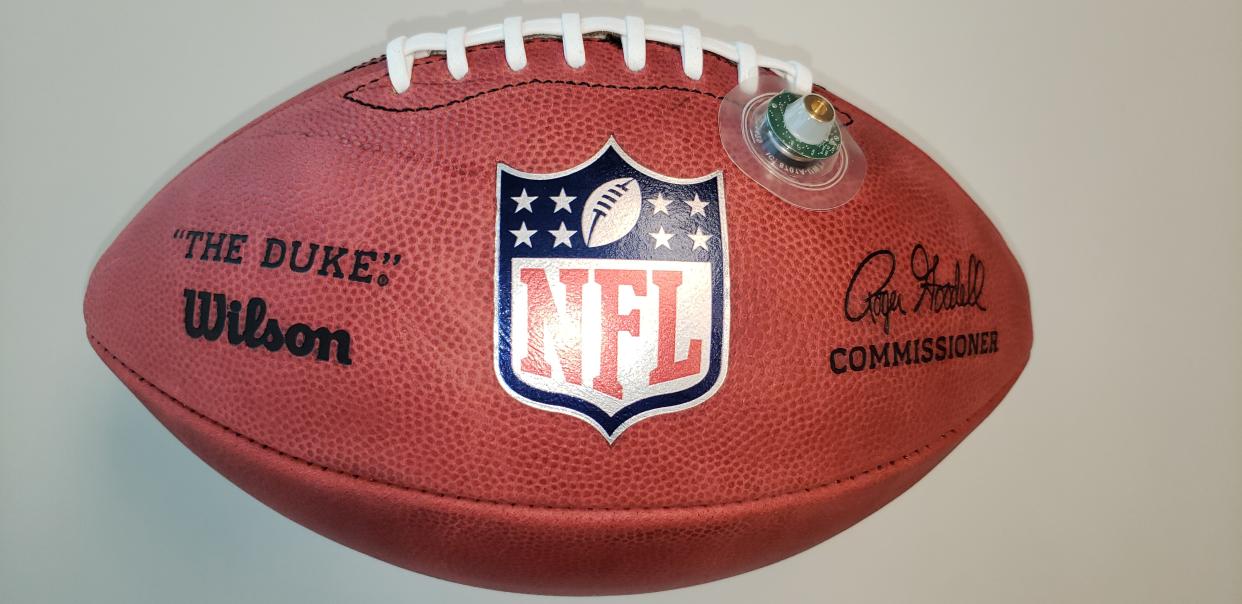

But in 2017, the league inserted a coin-sized microchip into its footballs. The chips unlocked a bottomless vault of data, and an ability to track the ball’s location. Initially, they weren’t used to aid referees. According to people with knowledge of the NFL’s technology, that’s changing.

Matt Swensson, the league’s vice president of emerging products and technology, said the tracking data now enables officials to adjust spots after punts fly out of bounds. Swensson also said the NFL is testing systems that would “marry up data and video” during replay reviews of touchdowns, like Jones’ in late October, and perhaps tell officials whether a ball hidden among bodies crossed an end-zone plane.

“We're trying to get a complete digital record of the game,” Swensson said. “And over the past couple years, we've built and we're testing some things around officiating.”

Implementation of such a system, though, is not imminent. Automation of officiating processes isn’t inevitable. Because, as Swensson said, “when you get into ‘did the ball cross the plane for a touchdown,’” using the technology “gets a little more complicated.”

The big roadblock

This conversation, around technological innovation in refereeing, is not new. Dean Blandino, a former NFL vice president of officiating, remembers having versions of it 20 years ago, “when the technology was still in its infancy.” Ever since, the tech has improved, and proliferated in other sports. In tennis, the Hawk-Eye optical tracking tool rules whether a shot was in or out. In soccer, a similar system tells referees within seconds whether a ball crossed the goal line.

To casual observers, the concept seems replicable in football. But, as those who’ve tried to replicate it explain, the NFL’s challenge is far more complex. In those other sports, the sole consideration is the location of the ball in space. In football, officials must determine the location of the ball when or before a player’s knee, forearm or other body part touches the ground. That, said Blandino, who worked at the league for two decades and left in 2017, has always been “the big roadblock.”

Any real-time automated ball-spotting system would need to detect not only the ball, but also every body part of the ball-carrier, and every whistle blown to rule forward progress stopped. The system would then need to sync those processes, and communicate a definitive conclusion to an on-field ref almost instantly. Some believe that’ll never be feasible. Swensson thinks that someday, “it could be possible,” but he admitted: “We're just not there yet.” And even if technological advancements made it possible, officiating and tech experts question how such a system could be implemented without disrupting the flow of a game. Terry McAulay, who worked as an NFL official from 1998-2017, imagines that hypothetical communication system being “very distracting.”

The league has instead focused on exploring how ball-tracking technology could supplement replay reviews. “Theoretically and technically,” said John Pollard, a vice president at Zebra Sports, the NFL’s on-field tracking provider, “it's feasible to use RFID [radio-frequency identification] technology to do that."

Marrying the technology

RFID tech allows NFL officials staring at monitors in New York to read data on the flight of a football. The virtually weightless microchips inside the balls weren’t initially designed to precisely locate them. But Pollard said they’re capable of “supporting [the] locationing of the ball, or identifying where a ball goes out of bounds, or potentially crosses a goal line.”

An optical tracking system, like Hawk-Eye, can’t do this alone, because footballs are so often obscured by bodies. But the radio-frequency system, either in concert with optical tracking or on its own, could help on plays like Jones’ goal-line plunge, when visuals seemingly don’t offer definitive evidence. The NFL and its tech partners could sync ball-tracking data with replays. Officials could view the replay, and decide when a player’s knee or butt or elbow touched the ground. Tracking data could then tell them, at that exact moment, whether the ball had broken the goal-line plane.

“I think that's the way to approach it,” Blandino said.

Swensson called this “a first logical step.”

The experts who spoke to Yahoo Sports also pointed out that sideline plays — whether punts or lunges for the pylon — are easier for the tech to assess. “Because at that point, you're really just talking about the ball and a location,” Blandino said. “A lot of spots at the sideline, the runner doesn't step out of bounds … the spot is where the ball crosses the sideline.”

Swensson, though, believes the RFID tech will be most useful in short-yardage scrums, when sideline cameras don’t pick up the ball. And that, unfortunately, is where the RFID tech is least accurate.

Swensson and Pollard said that its error margin is up to 6 inches, more than half the length of a football. That doesn’t mean readings are off by 6 inches every time. But they can be. “There are limitations to any technology,” Swensson said. Then he added: “You don't necessarily know the orientation of the ball. The tag's not in the tip of the ball. A lot of things can add up. We're not comfortable using ball tracking alone to say, ‘Did the ball cross the plane?’”

The narrower the error margin, the more comfortable they’ll get. Swensson mentioned “a couple of inches, with a level of consistency,” as a potential threshold. It’s unclear exactly how Zebra and the NFL will reduce it, or how they’ll marry video and data, but the one inevitability is that both the video and data will improve.

“I think the two working in concert would be very effective — or will be very effective,” Swensson said. “I just don't think we're ready to pull the trigger on that yet.”

Is ball-tracking technology worth it?

A key aspect of that decision-making process will ultimately be a cost-benefit analysis. How many incorrect calls, unfixable under the current system, would the technology correct? And will that accuracy, as Blandino said, “supersede the cost, and the manpower, the research, the technology,” without interrupting the flow of the sport and confusing or disillusioning viewers?

There were more than 40,000 NFL plays last season. Just 364 of them were reviewed. More than a third of the 364 were of a catch, interception or incompletion. Only a fraction of the remaining reviews were of a spot or goal-line crossing. Only a fraction of those delivered insufficient evidence to confirm or reverse the call on the field. And only a fraction of those calls that “stood” should have and could have been overturned by introducing data into the process.

“The availability of more information and technology is something that is worth considering,” Pollard said, but then added: “Can I say that it would absolutely change and evolve the game ... significantly? I can't say that. I don't know.”

The impact, for now, would be marginal, perhaps a dozen consequential plays over five months. That won’t stop the NFL from flexing technological muscle, and seeking to improve the game in granular detail. Especially when millions of dollars ride on every result. But absent “a widespread trend,” as Blandino said, or “an issue that is happening every game,” pressure to implement a high-tech system will be low. Only an Aaron Jones-esque incident late in a playoff game could up that pressure.

Absent it, the league will continue rigorous testing, implementing technology behind the scenes but not yet communicating it to officials mid-game. The system that now allows the NFL to re-spot shanked punts was tested “for years,” Swensson said, before the league quietly deemed it ready for showtime. Any goal-line or first-down technology will undergo a similar process.

There are no target dates, no timelines. And there is no eagerness within the NFL to eventually replace refs with robots. But, Pollard said, “there's a future out there where more information and technology is going to be in the hands of officiating crews.”

And if it aids them, and doesn’t slow or harm the sport, it’ll be welcomed.

“I think there will come a time,” Blandino said. “where we can implement it seamlessly, and we can be more accurate.”