God Shammgod's legend from streetball to Providence remains powerful

God Shammgod had just returned to his alma mater to finish his leadership development degree and plot his next career move nine years ago when he received a call from an old friend.

Chauncey Billups invited Shammgod to come to the Los Angeles Clippers’ game in Boston that night because Chris Paul wanted to meet him.

When Paul first spotted the ex-Providence point guard with the unforgettable name, the 12-time NBA All-Star blurted out, “Oh, man, no way!” Only after looking around to figure out who Paul was talking about did Shammgod eventually realize it was him.

The way Shammgod remembers it, Paul said that as a kid he loved watching Shammgod, that he spent months trying to master Shammgod’s flashy crossover dribble, that he might never have gotten into basketball were it not for Shammgod and Tim Hardaway. Sensing that Shammgod didn’t fully believe him, Paul took out his phone, dialed a childhood friend and put him on speakerphone.

“Who were we just talking about today?” Paul said. “Who did I used to emulate every day when we were playing basketball?”

“You talking about Shammgod?” Paul’s friend asked.

“I’m here with him right now!” Paul answered.

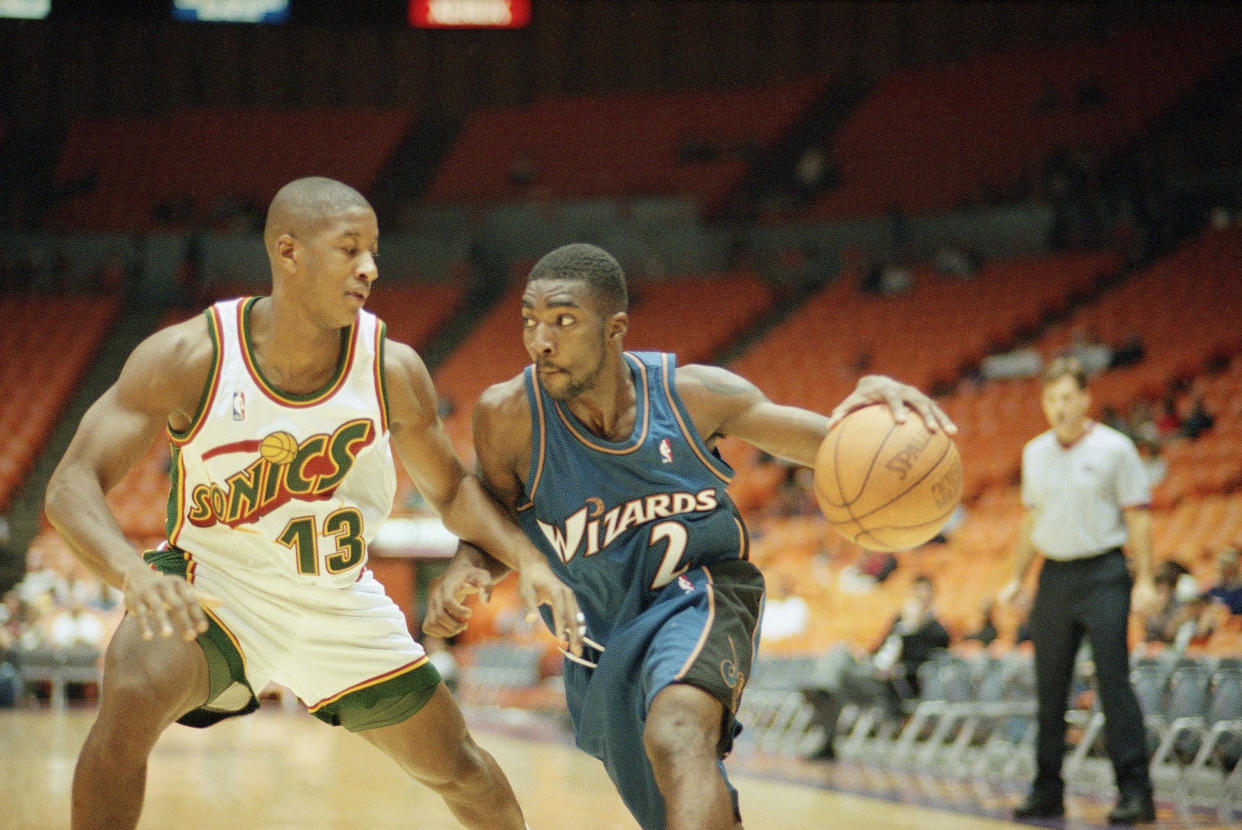

Stories like that reflect Shammgod’s impact throughout basketball despite barely making a ripple as an NBA player. Shammgod appeared in only 20 games and logged a total of 146 minutes with the Washington Wizards during the 1997-98 season, yet he remains revered and respected in basketball circles.

Twenty-five years after Shammgod first entered the national spotlight while leading 10th-seeded Providence on a memorable Elite Eight run, the deceptive crossover move that he popularized during that NCAA tournament is still known as “The Shammgod.” Russell Westbrook and Kyrie Irving are among the NBA players to attempt it in recent years.

Puma paid homage to Shammgod in 2019 by releasing a signature shoe in his honor. Artists like Jay-Z, Wale and Joe Budden have name-dropped Shammgod in their song lyrics. Spike Lee even once told The New York Times that Shammgod’s name was the inspiration for choosing the name “Jesus” for the lead character in the movie “He Got Game.”

The late Kobe Bryant credited Shammgod with helping him tighten his handle early in his career. As a result, when Kobe wanted to teach his daughter Gigi and her teammates how to dribble a few years ago, he flew Shammgod halfway across the country to lead those sessions.

As Providence returns to the second weekend of the NCAA tournament this week — the Friars face top-seeded Kansas on Friday night — for the first time since Shammgod’s heyday, the former Friars star looks back fondly on the run that catapulted him to national prominence.

“The NCAA tournament made me a household name,” Shammgod told Yahoo Sports. “It made a person that played 20 games in the NBA become more famous than people who were 10-year All-Stars.”

NBA legend challenged a teenage Shammgod

“God Shammgod?”

“Is that your real name?”

That was the type of question Shammgod answered incessantly as a kid. He’d often have to explain that, yes, that was his birth name and that, in fact, he was not the first God Shammgod. The original was his father.

Estranged from his dad for parts of his childhood and tired of the teasing his name induced, Shammgod adopted his mother’s maiden name and went by Shammgod Wells after moving from Brooklyn to Harlem when he was 9. He didn’t switch back until he enrolled at Providence and was told he had to go by his real name unless he forked over $600 to legally change it.

“It’s weird because as I got older, a lot of people told me, ‘That name fits you,’” Shammgod said. “After a while, I couldn’t see myself being named anything else.”

Shammgod’s transformation from a boy with a curious name to a basketball phenom began with his first visit to Rucker Park. Perched on the branch of a tree overlooking the world’s most iconic outdoor basketball court, Shammgod marveled at the skills and showmanship between the lines and the party-like atmosphere in the bleachers.

At one point, New York streetball legend Mike “Boogie” Thornton dribbled through the legs of unsuspecting defender Malloy “The Future” Nesmith. Awestruck spectators spilled onto the court clapping and laughing in amazement.

“That was the moment,” Shammgod says, “when I fell in love with basketball.”

The next day, Shammgod began working to become the best basketball player he could be. Back then, his idols weren’t Magic, Bird and Isiah. They were “Master Rob,” “Future” and “The Terminator.” He didn’t dream of sinking a game-winning shot at Madison Square Garden. His mission was to become well known on the streetball scene.

By 13, Shammgod had mastered some of the slick passes and slippery ball-handling moves that his favorite streetballers would try. Shammgod often showed off his latest tricks in gym class, delighting his friends but aggravating his PE teacher, who urged him to learn to play "real basketball."

At first, Shammgod dismissed the criticism, doubting whether Mr. Archibald knew what he was talking about. A few weeks later, he discovered that his PE teacher was actually Hall of Famer and six-time NBA All-Star Nate “Tiny” Archibald, one of the finest point guards New York City has ever produced.

Archibald asked if Shammgod was ready to listen.

Shammgod sheepishly responded that he was.

Thanks to the dribbling fundamentals he learned working with Archibald and the creativity he borrowed from streetball, Shammgod had what he now describes as “the best of both worlds.” He supplemented that by dedicating hours every day to his craft, practicing inside-out dribbles, crossovers, spin moves and going through the legs or behind the back. Typically, he’d practice with ankle weights strapped to his wrists. When he removed them, he found that his moves went from fast to turbo-charged.

Playing alongside Ron Artest at LaSalle Academy, Shammgod emerged as an elite playmaker, a pick-and-roll dynamo whose game was ahead of his time. All great New York City point guards could attack off the dribble. Only Shammgod controlled the ball like it was an extension of him.

“Most people who start out in streetball have flair but they don’t have the simple,” Shammgod said. “I was able to blend the two and make it my own.”

Friars' 1997 tournament run made Shammgod a star

In April of Shammgod’s senior year at LaSalle Academy, the nation’s 22 most ballyhooed high school basketball players descended upon St. Louis. The talent-laden 1995 McDonald’s All-American game featured 15 future NBA players and seven future All-Stars including Kevin Garnett, Paul Pierce, Vince Carter and Stephon Marbury.

Even among that galaxy of stars, Shammgod shined. Only minutes after checking into the game for the East team, the Providence signee went right at Pierce, first going through his legs and then behind his back to free himself for a jump shot. The next possession, Shammgod again went behind his back before whipping a one-handed pass to a teammate cutting to the rim.

“My goodness!” play-by-play man Verne Lundquist exclaimed.

“Greatest handle since Samsonite,” analyst Bill Raftery quipped. “He is a pleasure to watch.”

While Shammgod’s quickness, handle and court vision were Big East-ready, his exploits at the McDonald’s game masked how one-dimensional his game was at that time. He shot a mere 33.6% from the field as a freshman because opponents could sag off him and dare him to fire away from the perimeter.

As a sophomore, Shammgod improved his shot selection and led the Big East in assists, but he didn’t garner much attention during the regular season. For all his razzle dazzle, he was still just the fourth-leading scorer on an underachieving Friars team that never cracked the AP Top 25 and needed two Big East tournament victories just to solidify an NCAA tournament bid.

Everything abruptly changed for Shammgod and Providence once March Madness began. The 10th-seeded Friars came together to throttle Marquette, drop 98 points on Duke and avoid a letdown against Chattanooga, advancing to the program’s first Elite Eight since its Final Four run under Rick Pitino a decade earlier.

Shammgod’s finest game came in an overtime loss to eventual national champion Arizona in the Southeast regional final. He punctuated a breakout NCAA tournament by erupting for 23 points and five assists, outplaying future NBA lottery pick Mike Bibby and introducing the nation to a lethal new move that became his namesake.

Trailing 69-60 in the second half, Shammgod threw the ball out in front of himself with his right hand, took a couple steps toward it, then snatched it away in the opposite direction with his left. The maneuver left Arizona’s Michael Dickerson leaning the wrong way, freeing Shammgod to blow by him and attack the rim.

“When I went back to my neighborhood that summer, I was in the park and a little kid came up to me,” Shammgod said. “He was dribbling and he said, ‘I’m about to Shamm you, I‘m about to Shamm you.’”

At first, Shammgod was like, “What is he talking about?” Then he went to another park and found more kids imitating his move from the NCAA tournament and calling it “the Shammgod.”

“Pretty soon, it was everywhere,” Shammgod said. “It will help my name be here longer than I will be here and my kids will be here.”

In retrospect, Shammgod says he views Providence’s 1997 NCAA tournament run as “a gift and a curse.” While it helped immortalize his name, it also put him on a path toward a decision that he now describes as the worst of his life.

Falling out of the NBA

In April 1997, Shammgod chose to forgo his final two years of college and enter the NBA draft. He did so because some of his friends from the McDonald’s All-American game were turning pro, because he was listening to the wrong people and because he had a 2-year-old son he needed to support.

“It was a lot of bad advice, a lot of me doing stuff on my own and not getting all the information,” Shammgod said. “If I had known all the stuff I know now, I’d definitely have stayed in school.”

Shammgod vowed to become the NBA’s best point guard when the Washington Wizards drafted him 45th overall, but for a variety of reasons, he never got a real chance to showcase his talent. The coaches discouraged Shammgod from over-dribbling or busting out his streetball repertoire during a game. Shammgod also still hadn’t developed a jump shot defenders had to respect. And when he barely played behind veteran point guards Rod Strickland and Chris Whitney, Shammgod admits he “didn’t deal with that the right way.”

“At that time, I was young and hard-headed,” Shammgod said. “In practice, I was doing things that I felt showed I was ready, so when I didn’t play, that affected me. It was the first time in my life that I wasn’t playing, and I didn’t know how to deal with that.”

After washing out of the NBA at age 21, Shammgod spent the next decade playing in far-flung leagues around the world, from Poland, to Saudi Arabia, to China. When his overseas career began to wind down as he entered his 30s, Shammgod began to feel lost as to what to do next.

Inspiration struck Shammgod in 2010 when he returned to Providence to rehab a knee injury and agreed to hold private workouts for Friars wing MarShon Brooks. The joy of watching Brooks evolve into the Big East’s leading scorer and a first-round NBA draft pick the following year persuaded Shammgod to break his contract with his Chinese team and give coaching a try.

The following year, Shammgod re-enrolled in classes at Providence and asked permission to join Ed Cooley’s coaching staff as a grad assistant. Besides fulfilling a promise to his mother that he’d finish his degree, Shammgod got to observe Cooley’s “passion” and “attention to detail” up close while also continuing to hold workouts for Bryce Cotton, Ricky Ledo, Kris Dunn and other Friars players.

“As I saw how I could really impact players, that gave me more confidence I could really do this,” Shammgod said. “There’s an amazing feeling that you get inside when you’re helping somebody else. It’s not about money. It’s not about anything else. It’s just because you want to see them do good.”

By the time Shammgod became a college graduate, he no longer felt lost anymore. He knew that he wanted to help mentor and develop players the way Archibald once did for him — he just needed someone to give him a shot.

Lessons from God

In summer 2013, the Dallas Mavericks’ director of player development visited Providence to work with Ledo and happened to observe some of Shammgod’s workouts. Mike Procopio came away wildly impressed with Shammgod’s ability to “get players to buy into him and what he is teaching.”

“It wasn't about the drills,” Procopio told Yahoo Sports. “Drills are irrelevant in the field of making players better. It was his ability to look players in the eye and communicate.

“A lot of ex-players have no idea how to teach what they were good at as players. They just had a God-given gift and were able to use it. ... Sham would teach the small details and intricacies of handling the ball and position players the way he needed them to be. He never chastised players or talked down to them in a condescending way. He was one of them, he related to them, he got the best out of them.”

A couple years later, when several Mavericks players spoke of wanting to improve their ball-handling, team owner Mark Cuban came up with the idea of bringing in a coach to work specifically on that skill. Remembering the attention to detail and teaching skills that Shammgod had displayed, Procopio strongly advocated for Cuban to give the former Providence guard a chance.

When the Mavericks first offered to create a position for Shammgod in 2015, he actually had to turn that dream opportunity down. Dunn had decided to return to school for one more season and Shammgod promised the Providence point guard and his family he’d continue working with him until he reached the NBA.

“Dallas was like, ‘Well the job might not be here next year,’” Shammgod recalled. “I was like, ‘Yeah, but I can’t leave Providence yet. I made a promise to Dunn’s family that I can’t break.’ I put my faith in God, and the next year Dallas came back with an offer.”

While Shammgod’s reputation as a ball-handling savant got his foot in the door in the NBA, Procopio says he is “much more than that.” Shammgod has since ascended to development coach, and Procopio thinks “he will be on the front of the bench soon for someone.”

The way Cuban raves about Shammgod, maybe that “someone” will be the Mavs. In an email to Yahoo Sports, Cuban described Shammgod as “a great human” and said, “I love who he is.”

“What has really earned him his stay is his ability to relate to players and also teach [them],” Cuban added. “He truly is really good at his job.”

The lesson that Shammgod took from leaving Providence too soon a quarter century ago is not to be in too big a hurry. He has a loving family, a rewarding job, a network of friends, a shoe deal and the respect of a generation of basketball players.

“The decisions I’ve made have made me into the man I am today,” Shammgod says. “And from my standpoint, I think I’m doing pretty good.”