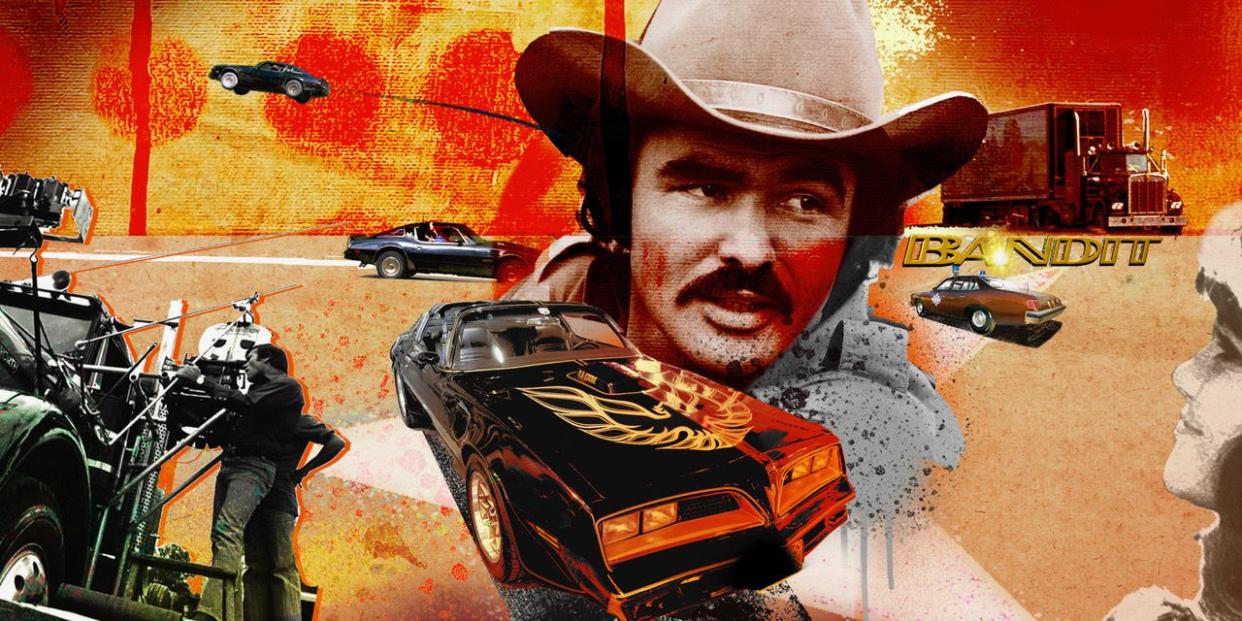

Smokey and the Bandit Moved Car Culture 45 Years Ago

According to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the “Best Picture” of 1977 is Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. That’s nuts. No one cares about that movie.

Only two movies made in 1977 still matter. Star Wars, before George Lucas started digitally screwing with it, and longtime stuntman Hal Needham’s Smokey and the Bandit. Neither were films their respective studios figured would make much money. But both revived genres once thought moribund. They have each effectively burrowed into the culture. And, 45 years later, they continue to be ludicrously entertaining.

There’s plenty of thumb-sucking considerations of Star Wars at 45 all over the Internet. The passion project here is Smokey.

Of course, you’ve seen the movie. And if you haven’t, how did you wind up reading this site? Anyhow, if it’s not playing right now on some backwater cable channel, it can be rented or bought from all the usual streaming outlets. It’s everywhere.

Smokey’s plot is bone simple. Big Enos and Little Enos Burdette (Pat McCormick and Paul Williams) make a bet with truck driving duo Bo “The Bandit” Darville (Burt Reynolds) and Cledus “Snowman” Snow (Jerry Reed) that they can’t get from Atlanta, Georgia to Texarkana, Texas, pick up 400 cases of bootleg Coors beer and return in 28 hours. If that feat is accomplished, they’ll get $80,000 – enough to buy a new Peterbilt tractor.

The complications come in the form of Carrie “Frog” (Sally Field) who is fleeing her wedding to Junior Justice (Mike Henry) and his father the obsessed Sheriff Buford T. Justice (Jackie Gleason). A pursuit across the south ensues.

“It was a bit of a lark when I agreed to do it,” Reynolds recalled in 2015, “and I knew we'd have fun if we could get Gleason. But then we got Sally on board and it changed the entire dynamic. About a third of the way into filming I was in the car with Sally and there was this little moment we kind a looked at each other and we both turned and looked over at Hal, he gave us a thumbs up and said ‘yeah!’ And we kind of knew it was some magic going on.”

Reynolds is at max charm in the blocker black Trans Am, Fields is super-cute, Reed brought great music and astonishing guitar picking in addition to his truck driving, and Gleason supplies most of the hilarity. The stunt work is solid and Mike Henry deserves some love too. Though it’s not like the critics loved it.

“This is a movie for audiences capable of slavering over a Pontiac Trans Am, 18-wheel tractor-trailer rigs, dismembered police cruisers and motorcycles,” wrote Lawrence Van Gelder in The New York Times May 20, 1977 review of the movie. “And just in the event that there is somebody out there incapable of recognizing the difference between a 6.6 liter Trans Am and a Hudson Terraplane or a new Peterbilt rig and a decrepit Reo truck, there is sufficient use of C.B. radios to let everyone know that while Smokey and the Bandit may not be a very original motor-mayhem movie, it is at least a new one.” Just the sort of review one should expect from a guy named… Van Gelder.

But it was the right movie for its cultural moment. During 1974, in response to the crisis resulting from the OPEC oil embargo, President Richard Nixon signed the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act that imposed a national 55 mph speed limit. That initiated a trucker culture incentivized to overcome (and undermine) the speed restriction and based around citizen’s band radios. Then, there was Nixon’s self-immolation amid the Watergate scandal.

Southern and rural culture, battered and diminished after a few decades of desperately needed reform, was battling for its soul. The civil rights movement had accumulated important legal victories in both courts and legislatures. Desegregation wasn’t just a dream, but (often deeply resented) public policy. Farmland was turning into suburban sprawl, wide concrete highways were replacing dirt roads, and Atlanta had gained NFL, MLB and NBA teams. By the mid-Seventies the South hadn’t yet redefined itself, but it was apparent that naked racism and gooey nostalgia for a mythic gentility wasn’t going to be adequate. Or acceptable.

The election of former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter to the presidency in 1976 seemed to indicate that the south was growing into something new and better. That it could reconcile its good ‘ol boy character with something approaching modernity.

More subtly, much of the greater American culture had been moving toward more urban, supposedly sophisticated media as advertisers added data analysis tools to their marketing plans. For instance, in 1971 the CBS television cancelled most of its countrified programs in favor of more topical and upscale shows. Despite still solid ratings, The Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres, and Mayberry R.F.D. all were axed as the network found new success with All In The Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and The Carol Burnett Show. It wasn’t just the size of an audience that mattered, but the desirable demographics of what audience was attracted. That abandoned audience was still out there, waiting for a cornball, goofball action comedy like Smokey to entertain them while validating their life choices. And beer.

Even though, ack, that included a Confederate battle flag as part of the Trans Am’s front license plate. The cultural standards of 1977 weren’t those of the 21st century.

Universal Studios, which released Smokey, didn’t initially know what they had in the film. And they opened first at Radio City Music Hall in New York City. “I don’t think it made enough to pay the Rockettes,” recalled Needham in a 2007 interview. “So they jerked it out. I said to them ‘I made this movie for the South, Midwest and Northwest, basically. So why don’t we take the damn thing somewhere where it was made for?’ They took it down south, the southern thirteen states, and it went right through the roof.”

Soon after that, even those New Yorkers had caught on and were eager to see Smokey. It couldn’t beat Star Wars at the box office, but it slaughtered everything else. Star Wars was number one for movies that year, and Smokey was number two.

“Something curious is happening to country movies,” wrote Vincent Canby in The New York Times on December 18, 1977. “Like country music, they are becoming a big, respectable if still largely unpublicized business.” The kind of movie, Canby contended, that people saw at drive-ins and featured a lot of action.

“What? You've never heard of Smokey and the Bandit?” Canby continued. “It's not the sort of movie that's talked about at cocktail parties. Yet it did play at Radio City Music Hall and it does star Burt Reynolds, one of the few major actors who crosses over between country movies and conventionally acceptable films.”

By the end of 1977, the entertainment industry was planning to do what it always does: imitate success. The rip-offs of Star Wars came immediately. And the rip-offs of Smokey weren’t far behind. By January of 1979 even CBS, the “Tiffany network” that had offed its rural shows in the early part of the decade, had its riff on the Smokey and the Bandit ready for the primetime lineup. It was called The Dukes of Hazzard.

Star Wars sold a bajillion toys, re-invented entertainment marketing and made fantasy entertainment commercially viable. It’s hard to imagine the Marvel Cinematic Universe existing if Star Wars hadn’t been there first.

No, Smokey and the Bandit has not had the same cultural impact as Star Wars. But Pontiac sold an unfathomable number Trans Ams after the film came out. The year before Smokey, the GM division sold a healthy 46,701 Trans Ams during 1976. That spiked to 68,745 during ’77, then pumped up again to 93,341 in 1978. Sales peaked in 1979 when Pontiac sold an astonishing 117,108 Trans Ams. That’s 250-percent more than in ’76. Today, a decent black-and-gold Trans Am like the one from Smokey goes for big bucks despite being as common as dust. It is simply the iconic car of the 1970s.

That was, however, a long-time ago. And Trans Am sales collapsed as the 400 V-8 was replaced by a crappy turbocharged 301 in 1980 and the Firebird was cursed with an ugly beak. The two Smokey sequels were, uh, not so good and not so profitable. Then there was a series of TV movies where the Bandit wasn’t Burt Reynolds and drove a Japanese-made Dodge Stealth instead of a T/A. Not great.

American still has a deep, southern, subculture. So, while the rural action comedy has faded away, that doesn’t mean it will never come back. In October 2020, The Hollywood Reporterwrote that a TV series was in the works with Danny McBride and Seth MacFarlane involved. Okay, whatever. Is America ready for a ten-episode, Smokey reboot on Peacock?

You Might Also Like